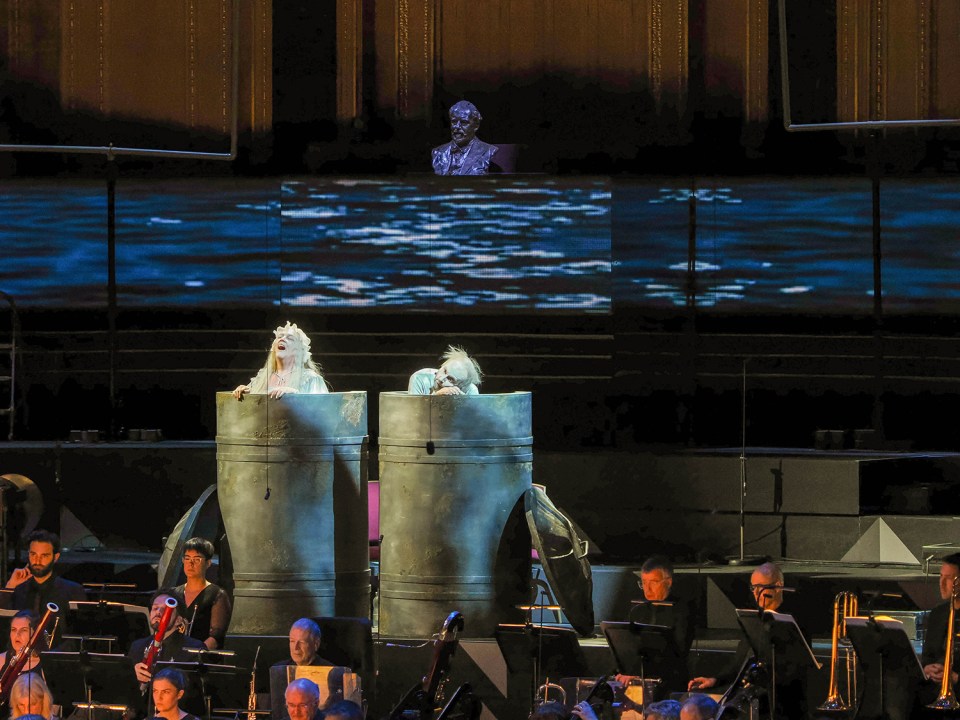

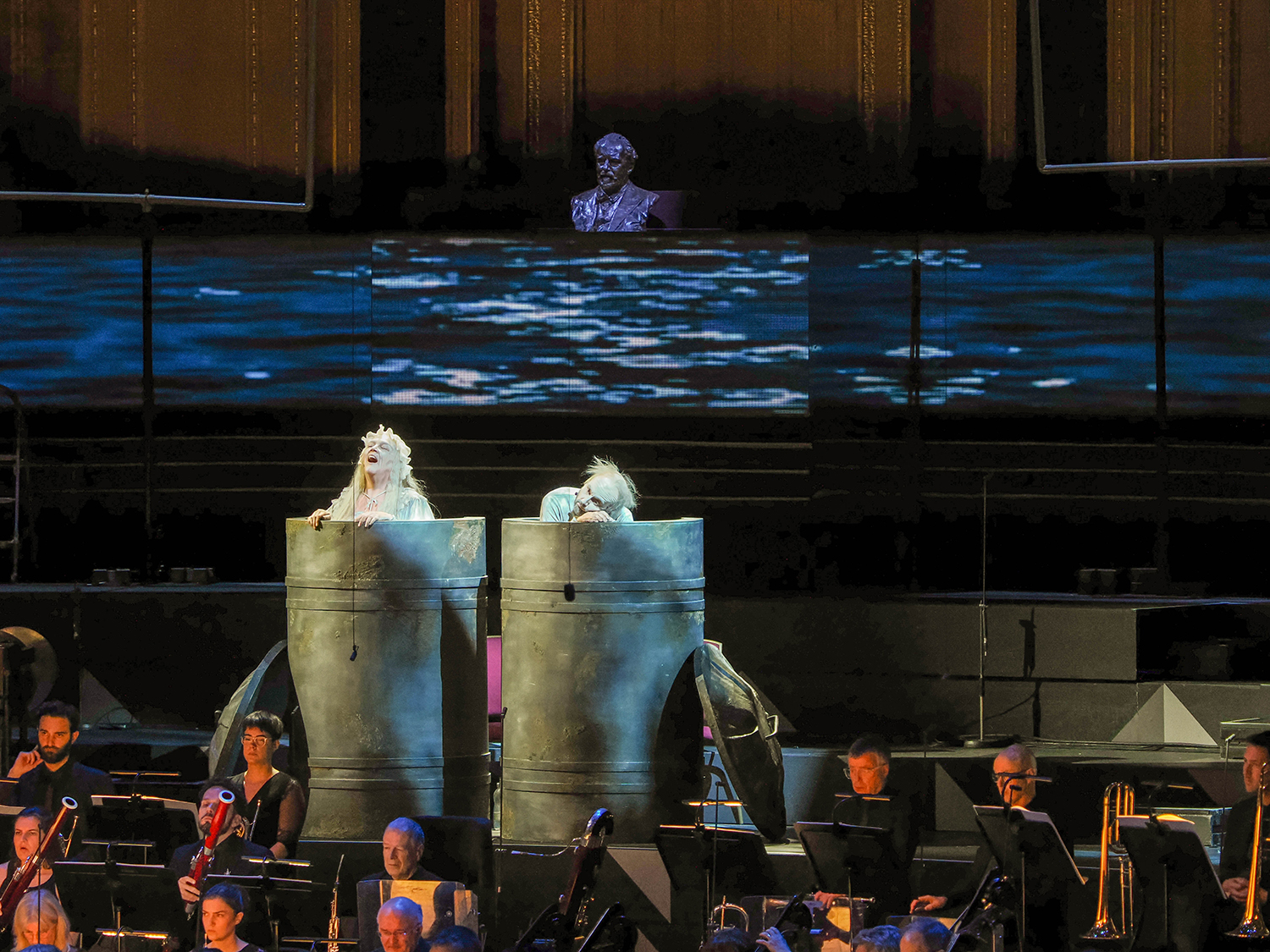

The fun starts early in Beckett’s Endgame. Within minutes of opening his mouth, blind bully Hamm decides to starve his servant. ‘I’ll give you just enough to keep you from dying,’ he tells Clov. One biscuit and a half. Which feels positively lavish compared with what composer Gyorgy Kurtag feeds us musically in the first 20 minutes of his operatic adaptation (receiving its British première at the Proms). Crumbs, we get. One single lonely tone, from one instrument, every few seconds, all so spaced out that it almost sounded like the orchestra was on tiptoe, glutes clenched, attempting a heist perhaps, trying to half-inch some notes from somewhere.

Every crumb of Kurtag’s music is a feast. A marvel of flavour and texture

But as Hamm says, ‘The bigger a man is the fuller and emptier’ – and Kurtag knows it. It’s one of the many miracles of Kurtag’s style that every crumb of music is genuinely a feast. A marvel of flavour and texture. As the work progresses the crumbs are swept together to form small heaps of what could almost be called music – tender, smudged portraits of each line, all shaded by instruments of the street. ‘Ah, hier,’ sighs Nell (the wonderful Hilary Summers) from her dustbin, a Russian accordion wheezing out the first bars of ‘Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’, from the film High Noon.

It’s easy to understand why so many worship at the feet of this 97-year-old Hungarian composer. Just listen to his use of the maracas, transforming this humble shaker into – if you can believe it – an instrument of emotional heft, as it periodically menaces the drama.

This is classic Kurtag. His obsessive tendency to boil everything down to a few gestures is a trademark. It would have been stranger if he hadn’t pulverised the orchestra. Yet it’s still shocking to see an ensemble treated like this, not as a well-oiled machine – cruising through the gears, like most composers are content to let it do – but deliberately hobbled, jammed up, sand filling the carburetor. Shocking and funny – and it’s always good to be reminded that Endgame is funny because it’s easy to forget. The superbly sensitive BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra – under conductor Ryan Wigglesworth – loped around forlornly, coughing up half-remembered melodies.

Top marks, then, for bleakness, for stark beauty, for being true to the cruelty of the play and its broken characters. Does the minute detail come at the expense of the dramatic whole? No doubt. Endgame’s absurdism, jump cuts, junkyard aesthetics, derives from the music hall, and orchestrally Kurtag exploits this beautifully. But Beckett’s dark vaudeville has a raw, rhythmic energy, a Punch-and-Judy dynamism, which evaporates if, as Kurtag does, you bunch most of Hamm’s dialogue into one long speech.

Kurtag always has a few more biscuits up his sleeve, however: such as when a shimmering octave materialises out of nowhere, like a rainbow, as Clov imagines escape: ‘When I fall I’ll weep for happiness!’

I must put in a good word for Gerald Barry’s première Kafka’s Earplugs, which got heckled (listen on iPlayer – Prom 26 – and you’ll hear a Yorkshire ‘robbish’ cut in before the applause) and duffed up by the critics, yet struck me as one of the boldest of the Proms crop. Ostensibly the work is the composer’s idea of what Kafka might have heard through his ever-present, specially made earplugs (the writer was tormented by the noise of everyday life). The result is a monumental slab of orchestral clay, all low, lumbering strings and smeared brass. Like the Kurtag, it doesn’t flatter the musicians or our ears. It commits to the bit. The bit in this case being something like the truth of what it’s like to trudge through a bog for 20 minutes – though Barry shifts to a brisker, more purposive pace in the second half as if remembering he’d left the oven on. A welly-level view of never-ending sludge: Barry’s Pastoral.

Both works are explorations of a kind of death. A living death. A lot of new music is. But then so was a lot of 19th-century music. Those of you sickos who prefer something more life-giving, however, should head to BBC Sounds and listen to the wild teeming garden of sound that is the Ligeti Violin Concerto from Prom 47. No shortage of music here: wasp-like skittering, possessed, drunken sawing, manic hoedowning and four-string pizzicatos that could take your eyes out. It’s hard to imagine another violinist or orchestra tending to these textures with more love or relish than the truly extraordinary Isabelle Faust and Les Siècles under François-Xavier Roth.

Barry’s Kafka’s Earplugs was heckled but struck me as one of the boldest of the Proms premières

At the work’s heart are packs of roving horns and strings, shorn of the civilising influence of the well-tempered scale, howling away in feral natural tunings. They attract a bevy of ocarinas (imagine the sound a Clanger might make after ten martinis), who stay to chat. For one night only, London had two zoos.

We’re always told no one enjoys these ill-mannered, uncompromising blasts from the postwar continental avant-garde. That the audience simply isn’t there for it. Yet here we were, at capacity in the Royal Albert Hall, 5,000 people lapping up late Ligeti as if it were The Lark Ascending. Let that be a lesson.

Comments