It might seem an odd choice, but after reading Jon Savage’s new book, I think if I had a time machine I’d now be tempted to set its controls for 13 January 1966 and the annual dinner of the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry. Andy Warhol had been booked to give a speech, but instead he put on a gig by the Velvet Underground and Nico at full uncompromising blast, with a couple of Factory favourites dancing alongside them. One shrink described the evening as a ‘torture of cacophony’; another — no less disapprovingly — as an ‘eruption of the id’. A third left hurriedly, with the explanation that ‘I’m ready to vomit.’

This clash between the old and the new, the squares and the hipsters, is, not surprisingly, a central theme of Savage’s latest lengthy rumination on pop music and its social significance — but it’s by no means the only one. ‘Pop was everything in 1966,’ he writes early in the first chapter; and, as it turns out, everything is pretty much what he attempts to cover in the pages that follow.

Of course, even in a book of this size, covering everything poses certain organisational problems, not all of which Savage solves. The plan, as laid out in the introduction, is for each chapter to pick a significant (and often impressively obscure) single for each month of 1966 and use it to explore one of that month’s wider social issues — at least until part two, from September onwards, when the scene apparently became too fragmented for that to be possible.

In the January chapter, Savage’s choice falls on ‘The Quiet Explosion’, the B-side to ‘A Good Idea’ by the Birmingham band the Ugly’s (chart position: unplaced), whose Cold-War lyrics indirectly lead him to the ringing declaration that ‘the pace of life quickened in the mid-Sixties and the fear of nuclear annihilation was the rocket fuel’ — one of many moments in the book where a Wikipedia editor might have added a stern ‘citation needed’. He then ponders youth angst with the aid of the rather better-known ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’, before moving on to such things as civil rights, Vietnam, LSD and the convulsed state of 1960s America.

The trouble, needless to say, is that these themes are not so much overlapping as wholly intertwined — and with Savage never sure how much to disentangle them, the chapters gradually collapse into something of a chronological and thematic jumble.

A clearer distinction, maybe because it’s a slightly artificial one, is between the book’s two parts. The way Savage tells it, from January to August 1966 pop music hurtled unstoppably along, developing at a never-to-be-repeated rate, and bringing the avant-garde and the mass-market closer together than they’d ever been. But then in September came the big crash. This was caused partly by the fact that the whole thing simply accelerated out of control — but also by the disappearance of the ‘centrifugal force’ of the Beatles, who following their beleaguered world tour in the summer had retired to lick their wounds. (One strange side effect of this disappearing-Beatles theory is that Savage pays very little attention to Revolver, surely the year’s greatest pop achievement.)

As a result, the music fragmented into its component elements: cheery mindless pop; serious, usually political rock, soon to be known as ‘underground’; black American dance music; old-school showbiz for the mums and dads; and the kind of garage music that American bands had been making in the early Sixties before being interrupted by those pesky mop-tops.

By the end of the year, too, the squares were fighting back, with Ronald Reagan elected governor of California and the Wilson government’s wage freeze marking ‘the end of the British high Sixties’. Meanwhile, the Aberfan disaster and the TV drama Cathy Come Home had provided jolting reminders that not all of Britain was swinging — or ever had been — and as Christmas approached, the top three singles were by Tom Jones, Val Doonican and the Seekers.

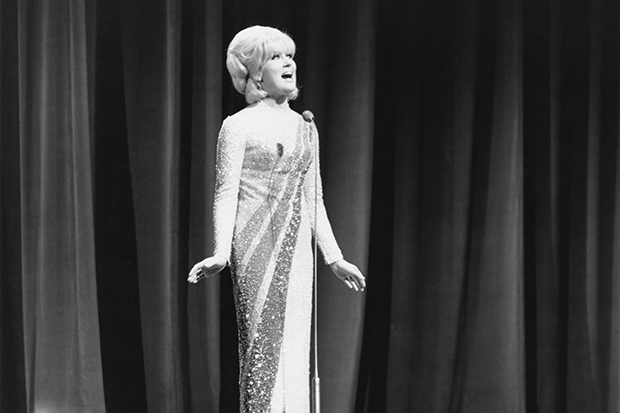

Throughout the book, Savage never wanders very far from his long-standing place on the more chin-stroking end of the music-writing spectrum. (At one point, he admiringly refers to Dusty Springfield’s ‘You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me’ as ‘a complex text’.) Fortunately, his earnestness never prevents him from capturing the excitement of the music or the speed, by turns thrilling and alarming, of the social change. Reading the book often has the arresting effect of making us realise what it must have felt like to hear these songs for the first time.

And yet, nearly 50 years later, it’s perhaps also time for a cooler eye to be brought to bear on the era. On the whole, though, Savage takes the radicals, mystics and champions of LSD entirely on their own terms (i.e. very seriously indeed), not even cracking a smile when an offshoot of the San Francisco Mime Troupe holds ‘a parade to celebrate the death of money’ — or when one British music journalist solemnly calls for ‘the total overthrow of everything’.

Admittedly, it’s never easy to combine unbounded and mostly justified enthusiasm with scepticism — or due reverence with a sense of humour. Nonetheless, the fact that it can be done was triumphantly proved a few years ago by Dorian Lynskey’s 33 Revolutions per Minute, a history of the protest song that covered much of the same material (and plenty more besides) just as rigorously, but with a much lighter touch, much more willingness to doubt its own heroes and, above all, a much greater awareness of the hubris and inadvertent comedy sometimes involved.

Savage, by contrast, sticks unwaveringly to the enthusiasm and reverence. The year 1966, he writes, ‘was a time of enormous ambition and serious engagement’ — a double that he himself is also clearly hoping to pull off here. But, while he generally succeeds, 1966 could certainly have benefitted from a more disengaged perspective too. As things stand, and for all its rich incidental detail, this remains a book that never really questions the long-received pop wisdom.

Comments