The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters

Royal Academy, until 18 April

Sponsored by BNY Mellon

From time to time we need to remind ourselves of the astonishing fact that Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) produced more than 800 paintings and 1,200 drawings in a mere ten-year career. He also wrote letters, of a depth and originality that qualify them as literature in their own right. So much to offer the world, such a sense of discovery and originality, yet he took his own life while still in his thirties. For decades, Van Gogh has been the artistic god of the self-taught and the misunderstood, making a particular appeal to the adolescent mind. I remember devouring my first book on him in an unusually quiet school dormitory during an influenza epidemic. Very soon I had graduated to the Fontana paperback of his letters and was quoting with approval such observations as: ‘I am a passionate creature, destined to do a number of more or less stupid things which later on I will have more or less to regret.’ It was, and is, heady stuff.

Van Gogh’s problem, and his making as an artist, was that he couldn’t lead a moderate life, but was compelled by his temperament to experience the extremes of suffering and joy. His solution was to transform his see-saw emotions into art, and for a time he thus made life bearable. The work he produced in the decade he did have is of a heartwarming, and occasionally heartbreaking, intensity. It is not easily ignored, though some of his admirers who went overboard as teenagers find it slightly embarrassing to return to his work for a more adult appreciation. This is a mistake: Van Gogh is great enough to appeal to all kinds of people, of all ages and distinctions. The new show at the Academy (the first big Van Gogh exhibition in London for more than 40 years) is already proving that.

There are seven galleries given over to a display of some 65 paintings, 30 drawings and 35 letters. One of the principal attractions of this show is supposed to be the letters, but such were the crowds when I attended, the letters would be a lot easier to study in the magnificent new edition, complete and annotated, published by Thames & Hudson. That said, the delights of glimpsing small drawings that were included in letters to Van Gogh’s brother Theo are indeed poignant; just a question of parting the sea of human bodies to find them. The visitor enters via the Octagon — look out for a back-of-envelope drawing of five men and a child in the snow — and then progresses into the first room of dark-toned realist pictures, such as ‘Autumn Landscape’ (1885). Next to it is ‘Avenue of Poplars’, in ink, a superb letter-sketch (rather more interesting than the painting) and what a treat to find in the morning post.

The drawings are in fact one of the main attractions of this excellent show. Look, for instance, at ‘A Marsh’ (1881), a large study in ink and graphite with the kind of all-over mark-making you might find in a closely worked etching of an earlier period, but with a remarkable sense of light breaking through the surface. The subjects are very Dutch — pollard willows, canals, flat expanses — and in room two this broadens to include the peasants who cultivated the land. Tough black chalk drawings of figures digging, planting, reaping or binding alternate with domestic scenes of sewing or peeling potatoes. This is not the Van Gogh that most have come to see, being too earnest and full of toil. Gallery three offers a lightening of the palette with a whole slew of fabulous flower paintings (particularly interesting being ‘Vase with Field Flowers and Thistles’), culminating in the delicious ‘Flowering Garden with Path’ (1888) on the end wall. On the other side of the room, two ink drawings of fishing boats, hung with an oil of the same subject, once again put the painting in the shade.

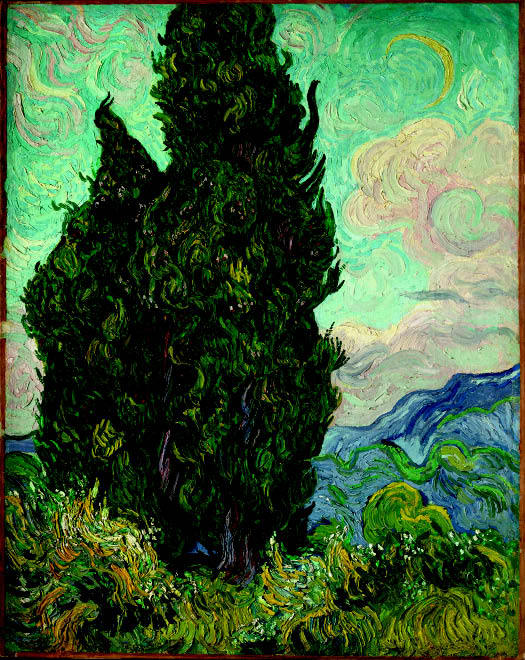

It is the amazing variety of mark that Van Gogh achieves in his drawings which is so transporting. Using a reed pen and sometimes a quill, he makes patterns and textures beyond the call of mere description, in cascades of ink strokes both wet and dry, scratchy and fluid. The speed and invention of this notation, its passion and rhythmic authority, are undeniable. But if the drawings are one of the glories of this show, the selection of paintings is another — an intelligent mix of old favourites and relatively unknown images. Entering gallery four, the visitor is greeted by the only self-portrait in the show and the beginning of an absolutely breathtaking succession of masterpieces. Postman Roulin and his family mingle with peach and apricot trees in bloom. Among the most beautiful paintings are ‘Arles in the Snow’ (1888) and ‘Wheat Fields after the Rain’ (1890), but there are too many marvels to list. Despite its smug and irritating title, this is a first-class exhibition and deserves to be a huge success.

Quite a different degree of talent, but a notable skill in drawing nonetheless, may be seen in a special display of Thomas Hennell (1903–45), one of the great artistic casualties of the second world war, showing at the Watercolours and Drawings Fair, 3–7 February, this year held at the Science Museum in South Kensington. A friend and colleague of Bawden and Ravilious, Hennell was a powerful draughtsman and painter in watercolours, as well as a writer, poet and illustrator. He specialised in country subjects, and in recording the rural traditions that were dying out in the face of mechanisation, but also worked as a war artist in Iceland and the Far East. The display is organised by Sim Fine Art and on Andrew Sim’s stand you may see a loan collection of Hennell’s war work from the RAF Museum in Hendon (currently closed to the public), together with other examples of his little-known oeuvre, including portraits. A remarkable artist who deserves to be more widely appreciated.

Comments