Do you think the luxury soap-maker Aesop would have been valued at £2 billion pre-pandemic? I don’t. Sure, the botanical Aussie cosmetics brand, famously seen in the prettiest restaurants and lining the bathrooms of the fashionable, has been valuable for some time, but ‘hands, face, space’ propelled its growing stardom into a multi-billion pound lather. Today, having one of the cult bottles on the basin is as ubiquitous a status symbol as driving a 4×4 around Chipping Norton.

L’Oréal announced this month that it has signed an agreement with Natura &Co, the brand’s owners, to acquire Aesop in a deal worth $2.5 billion USD (around £2 billion). In 2018, Aesop had net sales revenue of £214 million, and today it has more than 200 shops across 29 countries: not a bad trajectory for a product that started out being sold from a single suburban hair salon in Melbourne, Australia, in 1987. Apparently the move will help L’Oréal find firmer footing in China, which strikes me as rather ironic.

On a more serious note, here we are in 2023, and Aesop, most notably its flagship ‘Resurrection Aromatique Hand Wash’, is avocado on toast. That is to say, it has become a priority for the aspirational. The moneyed will buy lavish handwash because it exists; young professionals want it because, for 30 odd quid for 500ml, it is a moderately accessible point of focus that enriches the soul and solidifies a place in bourgeois society. After all, rented flats with expensive soap are what millennialism is all about.

To be cynical is to live, but Aesop is ubiquitous in middle-class homes for a reason. Bottles come in understated, coolly brown transparent glass, a homage to the Victorian apothecaries of old. The typography on labels looks scientific – a design-led blend of Helvetica and Optima, sleek and stylish – and its appearance in bathrooms, commercial or household, is elevating.

There are reports of people pinching Aesop from hotels, bars and restaurants. Never mind that its heavy fragrance leaves the hands so perfume-laden that the taste of food and drink is altered in the immediate aftermath of a trip to the loo. There are stories too of people refilling Aesop bottles with cheaper alternatives so they can continue to display them in their bathrooms. They might use Aldi’s knock-off, which is almost as well executed as the supermarket’s less than tame riff on Jo Malone candles, another mainstay of faux opulence.

Really, Aesop is the first acceptable cult since Pret a Manger. It is a step or two above middling tuna baguettes, certainly – upper middle-class to the everyday white-collar commuter – but here we are witnessing the culmination of an extraordinary rise.

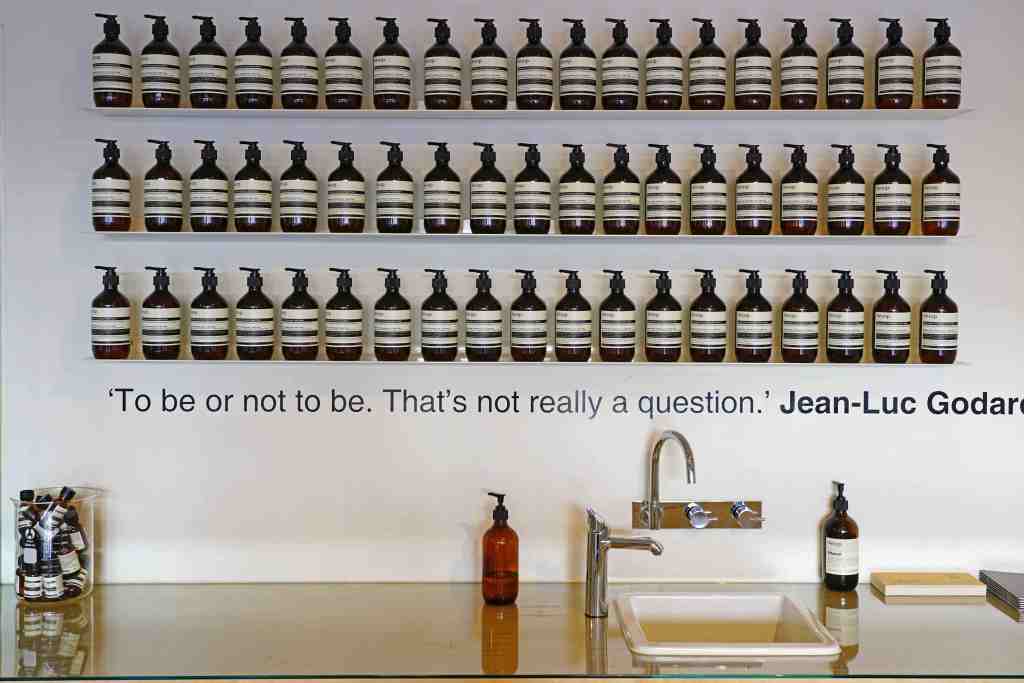

If you suppose attaching the label of ‘cult’ to the manufacturer of a sensorial soap brand is a little far-fetched, consider the fact that people who work for the company are described as ‘Aesopian’, as the Daily Telegraph reported. Quotes by St Francis de Sales and George Bernard Shaw appear on the website; Jean-Luc Godard on the shop wall. In a 2019 book on the brand, titled (unsurprisingly) Aesop, founder Dennis Paphitis mentions the scattering of autumn leaves on shops floors and of store fronts with eucalyptus oil to enamour those walking by.

It is a charming sort of cult, built on the shoulders of its eponymous Greek fabulist. Cults need a story and the handwash has one – as earnest, intriguing and lyrical as any ancient tale. It is one of ‘essential oils’ – the likes of orange, rosemary and lavender. It is one of woody aromas, feeling ‘cleansed and refreshed’, of the benefits of the restoratively herbaceous.

So perhaps it isn’t any wonder, given the state of things, that the remedial clutches of a well-scented bathroom product has drawn us in. We, the great unwashed, must be replenished, and the gilded world of Aesop is a gateway to something more, even if ‘more’ is merely washing our hands in the toilet of a cocktail bar in Haggerston.

I do not for one moment doubt the quality of Aesop. Surely there isn’t a more emphatically made handwash. It sets the tone with a pinpoint aesthetic. But we might also be aware that, probably, we have all been a little duped. What seems like a bashful brand – it has never advertised – must be calculated, too. Because actually there is no escaping the fact that an Australian man has convinced us (and I include myself in this, absolutely) that spending £70 on a pot of hand balm is completely normal.

Comments