Sylvain Tesson’s White unfolds the story of a gruelling ski journey across the Alps during which the author aims to fulfil ‘a long-held dream of transforming travel into prayer’.

Born in Paris in 1973, Tesson is a well-known adventure writer whose previous books include The Consolations of the Forest: Alone in a Cabin on the Siberian Taiga, which won awards on both sides of the Channel and was made into a film. As a public figure associated with the far right, Tesson remains divisive in his homeland. His political views do not seem to have dented book sales or literary coverage: one wonders if the same would be true if a travel writer of similar persuasion popped up here.

‘Snow imposes the sky’s thoughts on the earth,’ says Tesson, revelling in the French fondness for the abstract

This latest caper spreads over four winters, 2018 to 2021, kicking off on the Mediterranean coast of France. Proceeding north to Switzerland, then turning due east, Tesson’s route follows the curve of the Alps to Austria before dipping south into Slovenia and concluding on the Adriatic at Trieste. It takes 85 days altogether. Tesson is accompanied throughout by a saturnine mountain ski guide and, for most of the journey, a Swiss engineer met by chance at the outset.

The trio sleep mostly in mountain refuges, scraping frost off mattresses, setting out by the light of their headlamps and smoking cigars during breaks (Toscano Extra Vecchios are ‘the only ones that don’t go out until their smoker does’.) Sometimes they take cable cars (to the summit of the Aiguille du Midi, for example) and even occasionally trains (as when they skirt the Swiss Grisons).

Fluently translated by Christine Gutman (White appeared in France as Blanc in 2022), the book is set out diary-style, the material broken into four parts, one for every year of the journey. Each winter the skiing mountaineers start where they left off on the previous trip. The book includes only the briefest of references to world developments in between (fire destroys the spire of Notre-Dame and the iPhone 11 arrives – as does Covid). Tesson doesn’t seem to mind what happens, proclaiming: ‘Escape… the noblest profession in the world.’

His agreeable descriptive prose conjures mountains ‘lacquered in light’, ‘the rocky dorsal fin’ of a deep pass, an ‘acrylic sky’. But it is the inner journey that engrosses him. ‘Even the easiest climb’, he discovers, ‘dissolves time, expands space and pushes the mind deep down into the depths of the self.’ This notion lies at the heart of White: the experience of ‘self-dissolution’ as the world melts into a dazzly blob. Tesson writes lovingly of ‘the disintegration of the ego’ faced with the grandeur of nature, and of the facility of his snow journey to annihilate anxiety and ‘wash away bitterness’. An uplifting idea, if not an original one.

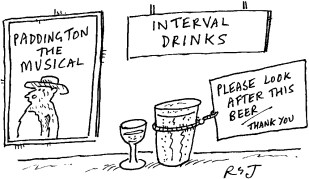

Yeasty direct speech leavens the mix, even if the device of a tripartite comic chorus intoned by the three protagonists fails to hit any mark (the book is notably devoid of humour). Tesson revels in the French fondness for the abstract, and Anglo-Saxons might find some of the philosophising gnomic. ‘Snow imposes the sky’s thoughts on the earth,’ he announces early on, for example, without explaining what the sky might have on its mind. When he does want to tie himself to something specific, he reaches for metaphor. Snow turns out to be ‘the bride, the veil, the vow; sexual purity and cosmic force; the matrix of forgiveness and cleansing, which we [he and his two companions] would seek never to leave’.

The most interesting sections concern practicalities rather than lofty thoughts – when the men have to peel the skins off the base of their skis and switch bindings to downhill mode; the mechanics of climbing with ice screws; how to rappel. I enjoyed learning the protocols of attaching an ice axe to a backpack. Paragraphs quickly take on the pleasant rhythm of each day’s departure from the hut and the ‘endless back and forth between exertion and recovery’.

White is a literary volume: almost every page is larded with quotations from Heraclitus to Victor Hugo and far beyond. The emotional climax of Tesson’s parallel voyage into the works of other writers comes in the middle, with several lively pages on the poet Rimbaud. The three skiers yell dear old Arthur’s hallucinatory verses as they hurtle towards the Dolomites.

Does Tesson succeed in his ambition to ‘transform travel into prayer’? Yes, to a certain extent. But release from the bondage of self – that’s what he’s on about, really – is hard to convey on the page. And where does all this rumination leave the reader? I closed the book with the itchy awareness that no voyager can forestall the final avalanche, as Rimbaud discovered far from the snows.

Comments