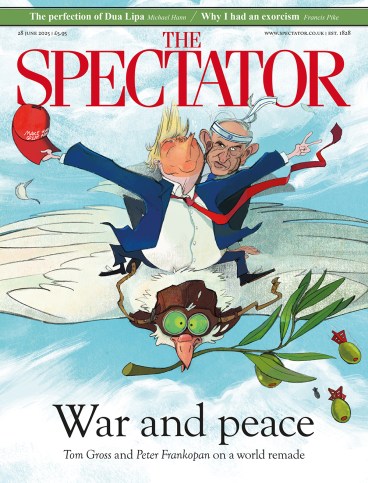

Right before the end of my game against Alexei Shirov at the World Rapid Team Championships earlier in June, I had the better side of a drawn position and a full 20 seconds to make a move. Not too bad: Shirov is a former member of the world elite, whose brilliant games I had revered since childhood, and a draw would secure us victory in the match. At that moment, my mind left the chessboard. It pondered the winning position I had earlier in the game. And it drifted back, yet again, to the middlegame, which reached the position in the diagram below, right after I, playing Black, had captured a knight on f5. In response to 23 Nxf5 I intended Qxb2!, when White must choose between 24 Rxg7+ and 24 Nxh6+, but in either case Black emerges from the skirmish with an extra knight.

What actually happened was this: Shirov picked up my knight on f5, and slowly, calmly, used it to capture my pawn on h6. That is not a chess move! Those are both my pieces! Realising his mistake, he apologised and put the pieces back before playing 23 Nxf5 Qxb2 24 Nxh6+. (Clearly, Shirov was ‘thinking ahead’ to his 24th move, and tried to execute it at move 23). After 24…Kh7 25 Re1 gxh6 26 Rge5 Nd7 27 R5e3 Qf6 I had a winning position. But I also had a persistent attack of the giggles. Shirov was tenacious, and my advantage dissipated.

An arbiter’s gesture interrupted my reverie. He pointed at my clock: I had lost the game on time. I put my head in my hands before conceding.

Shirov’s mishap had an element of fortune. The piece he picked up first – my knight on f5 – was the piece he intended to capture anyway, so the ‘touch-move’ rule (i.e. if you touch a piece, you have to move it, or capture it, if such a move is legal) did not interfere with his plans.

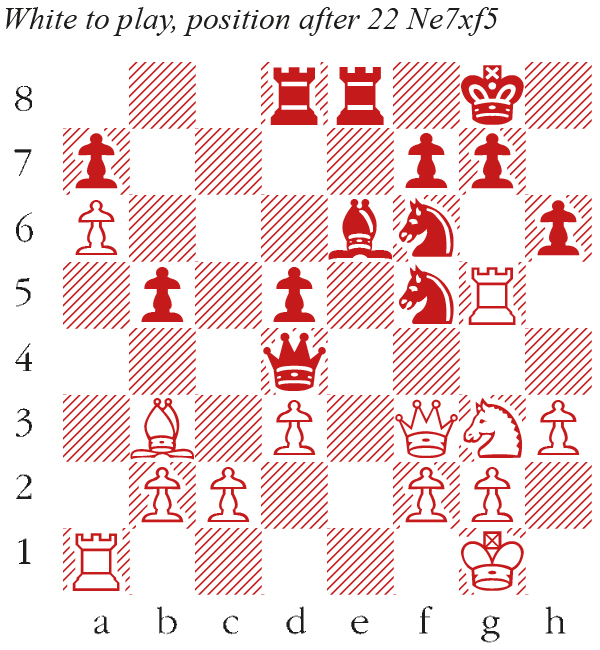

After the game, I learned of a similar incident at the 1980 Olympiad in Malta. Krum Georgiev, as White, had played a sparkling game against the future world champion Garry Kasparov. In the diagram, Kasparov’s bishop has just captured a pawn on e7 and everyone expects 21 Bg5xe7, with a winning endgame advantage for Georgiev. Instead, he made the bizarre and impossible move Be7xd6, presumably ‘thinking ahead’ in the sequence 21 Bxe7 Nbc6 22 Bxd6 (rather like Shirov). A lengthy dispute arose concerning whether Georgiev had first touched the d6-pawn or the e7-bishop. In Kasparov’s account, it was the the pawn, in which case the ‘touch-move’ rule would mandate the ludicrous move 21 Rxd6, which loses a rook. The arbiter eventually ruled in Georgiev’s favour. He played 21 Bxe7 and won the game 40 moves later.

Comments