Fawlty Towers at the Apollo may be the best museum piece you’ll ever see. A full-length play has been carved out of three episodes: ‘The Hotel Inspectors’, ‘The Germans’, and ‘Communication Problems’ in which the deaf guest, Mrs Richards, made a nuisance of herself by refusing to switch on her hearing aid in case the batteries ran out. For anyone who saw the sitcom in the 1970s, this is a pleasantly weird show. It’s like returning to a seaside funfair after half a century and finding all the rides unchanged and the staff more or less as you remember them.

If Beckett had written family comedies he might have created something as amusing as this

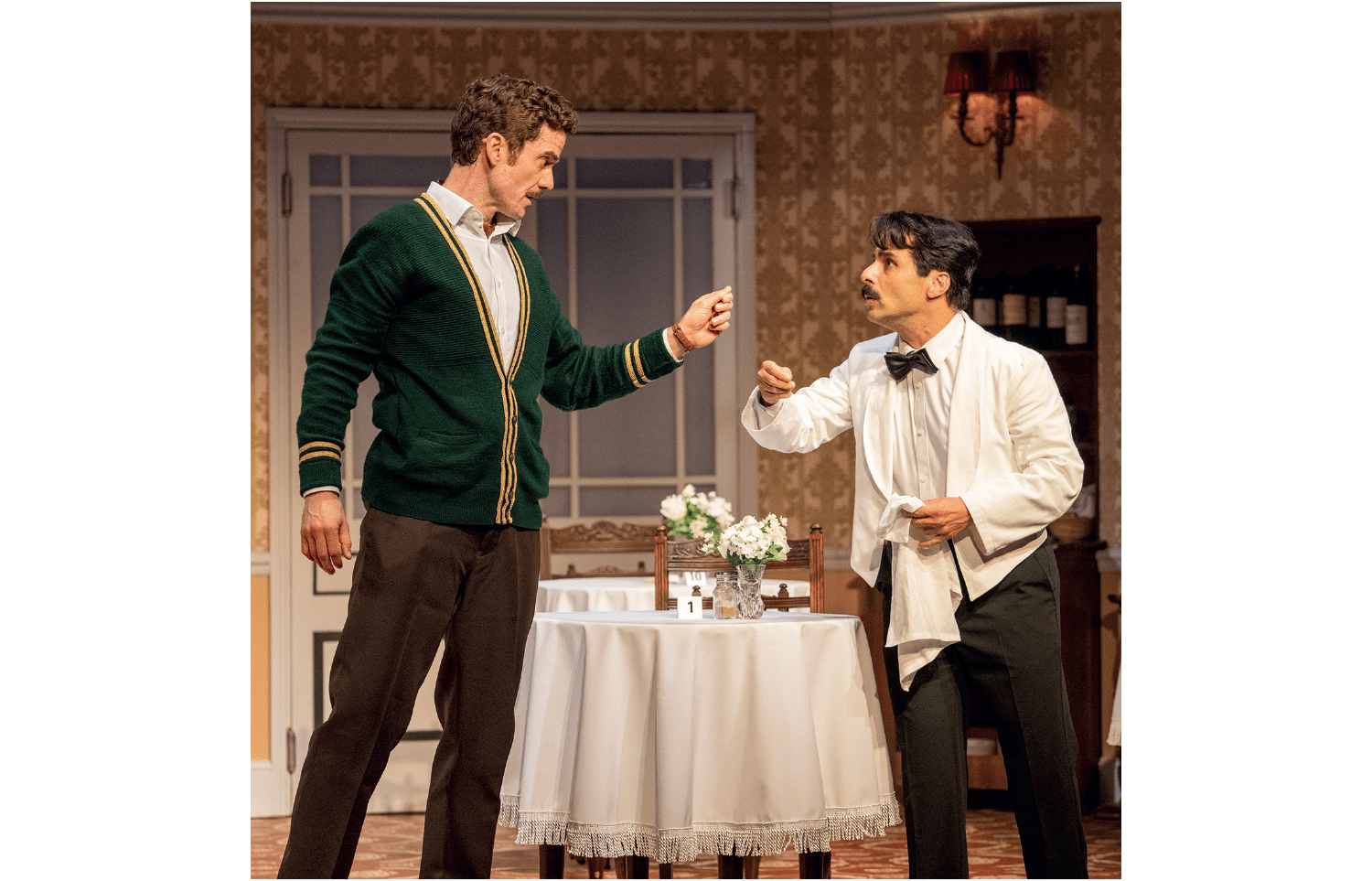

Paul Nicholas makes an even better Major than the Major. And his rich, fruity voice is an unexpected treat. Manuel is played by Hemi Yeroham, who hadn’t seen the show before he landed the role. He adds a few personal touches that work very well and he’s at least as likeable as Andrew Sachs – plus, he’s better looking. Anna-Jane Casey (Sybil) gets a round of applause just for walking on stage with her famous bee-hive hairdo. Her domineering spikiness comes across brilliantly. And Adam Jackson-Smith delivers the most precise and carefully studied facsimile of Basil. Actors hate being told this but by adding nothing new he gets it exactly right. His only failure is the goose-stepping Hitler routine, which is beyond him physically because he lacks the height for it and can’t flex his limbs with Basil’s crazed athleticism. But who could? Cleese’s record as the best Hitler impersonator in history remains unchallenged.

The show’s ending doesn’t quite work, as Cleese is doubtless aware. The problem is that an episodic TV show is a different beast from a one-off drama. A sitcom usually ends with an enjoyable flourish that leaves the basic set-up unaltered. But a full-length play needs a larger and more explosive climax that changes the characters and the story permanently. It’s impossible to fashion such a transformation from a few sitcom endings. Cleese once predicted that his classic comedy would grow stale and fade into oblivion. Time is proving him wrong.

Sophie Treadwell’s Machinal, written in 1928, is a horrific ordeal, a nightmare, the absolute antithesis of entertainment. The play is a tale of murder in which every character is innocent, and yet it involves an unjustified act of violence. The show opens like an absurdist soap opera about urban wage-slaves. A young woman is shunted to work each morning by a jolting commuter train that delivers her to an office full of automatons who create nothing but noise, stress and pointless activity. Then we get a softer scene. At home, the woman eats supper with her obtuse but kindly Irish mother. From the neighbouring flats come the cries and squabbles of married couples raging violently at each other.

The woman explains that a colleague at work is paying her attention. He’s a vice-president. He admires her hands. He proposes marriage. She mentions that the man’s fat fingers make her blood run cold but she knows she must accept. Her mother expects her to marry and she meekly obeys. This short scene is brutally funny. If Beckett had written family comedies he might have created something as horribly amusing as this.

Next we meet the husband who is decent, harmless and dull. After their awkward honeymoon, the woman gives birth and her nightmare moves to a clinic where the doctors and medical students poke her like a specimen in a lab. Her nice husband arrives and he tells her that he lived through every moment of her ordeal, listening from the corridor outside. This scene is staged on a small triangular playing area painted a ghastly yellow. It feels like a dead end or like the ledge of a building above a lethal void.

The woman starts an affair with a charismatic drifter who recalls his adventures among bandits in Mexico. He explains that he killed a man using an empty whisky bottle crammed with small stones. ‘First it’s a sledge-hammer, then it’s a knife,’ he says. As soon as we hear this we know that the woman will murder her husband by improvising a similar weapon from their domestic glassware. This horrible realisation haunts every moment of the second act. To compound our sense of revulsion we know that the husband has done nothing to deserve his death. Most strangely of all, we understand why the woman feels obliged to sacrifice him and to forfeit her life as well – because she must die for her crime.

In the closing scenes the woman loses touch with humanity and descends into a mass of screeching hysterics. This is unsatisfying but it’s what the playwright wanted. If your taste is for difficult, challenging, painful theatre, here it is: as fine a production of this harrowing play as you’ll ever see.

Comments