It’s lovely to be the child of a Chinese Revolutionary Martyr. It means your parent died especially heroically for the Communist cause. I had a friend who was such a son; his father, a high-ranking Chiang Kaishek army officer, came over to the Maoist cause and died fighting for it against his former comrades. The big thing for the son was that he had access to his dang-an, the official dossier containing the personal and political details of individual Chinese, which is closely guarded by the security apparatus. Few ever see their dang-an — which can make or break your career — but my friend could add favourable facts to his and excise damning ones.

It follows that it is a very bad thing to be accused of not being the genuine son or the grandson of a RM, especially if you once enjoyed many good things, including career advantages and public esteem on the strength of such a pedigree. It makes no difference if you believed you were genuine.

Such are the fates in The Boat to Redemption of Ku Wenxuan, the son of the woman martyr Deng Shaoxiang, and of her grandson Ku Dongliang. A secret courier for the Communist side during the civil war before Mao’s victory in 1949, Deng was hanged by the enemy, leaving behind, it was always stated, a baby son with a fish birthmark on his backside.

When baby Ku grew up, famed for his lineage and his birthmark, he became a big shot in Milltown, a smallish place on a river. But doubts grew about his authenticity, which he himself had never questioned; after many other boys and men flaunted similar birthmarks he was disgraced. He spent the rest of his life working on a river barge with his similarly disgraced son, but never stopped sending letters to officials begging for reinstatement as a RM.

Increasingly depressed, Ku attempted to cut off his penis, out of shame at his deserved additional reputation as a womaniser. He stayed out of sight, fearful of people’s pointed looks at his crotch. His son was equally shy about his crotch because of his many erections, for which his father, who knew a lot about sex, constantly chastised him.

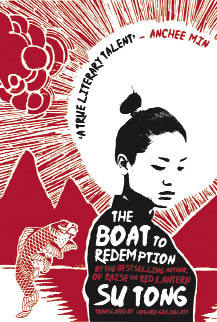

Summarised like this the book sounds peculiar and unappetising. But Su Tong, the author of the novella Wives and Concubines in Droves, made by Zhang Yimou into the film, Raise the Red Lantern, that nearly received an Oscar, is a good writer, well-translated here by the incomparable Howard Goldblatt. Su Tong skillfully tells a bleak story about rural and river life in China during the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976. Essential elements of this life remained true in China for decades afterwards. If one lives in China, as Su Tong does, describing such life requires two kinds of skill: writing, of course, but also deftness to avoid being nailed as a counter-revolutionary, a fate always lurking near Chinese writers. Any Chinese reader will recognise what Su Tong is actually doing — which is showing how fears of official persecution hover over the whole Chinese landscape and how those with ‘difficulties’ are shamed forever. In the case of Dongliang, no longer a RM’s grandson, he became a kongpi, ‘empty fart’, the name by which he was addressed.

Because Spectator readers are not Chinese, they may find all this baffling. Everyone, except the illiterate barge people who float by most of the political and social traps, fears persecution, social condemnation and envy. One can soar high on one’s status, as did Dongliang’s father, his mother who was a famous local actress, and the appealingly drawn orphan girl, Hui Xian. Characteristics, sexual rumour and gossip flood through Milltown and help bring down the disgraced Ku Wenxuan and his constantly humiliated son.

Su Tong masterfully skates over the political implications of his story while exposing, not with a bludgeon (often the style in Chinese novels) but with scalpel-like precision, the social fault-lines that are used by the Party to guarantee what it calls ‘stability.’

No one is safe in Su Tong’s world, except the bargees, who are never anywhere long enough to become targets or victims. Dongliang muses on the perils of losing the aura of descent from a Revolutionary Martyr — the evidence always secret, the conclusion always devastating.

I got a lot out of this bleak story but kept in mind what Su Tong didn’t dare to say out loud.

Comments