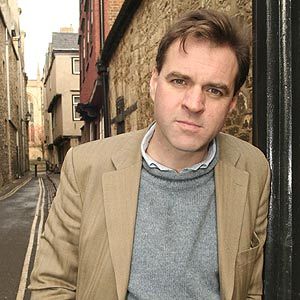

The last episode of Niall Ferguson’s documentary series, Civilization,

has just been aired — and for those who missed it, it’s time to buy the

DVD box set. Or, better still, read

the book. Ferguson is, for my money, one of the most compelling, readable and original historians writing today. His books stand out for throwaway lines which can change the way you think about

what’s happening now. Understanding of history shapes our politics, whether we admit it or not. And myths about history also fuel political myths. How often do we hear it said that the Great

Depression came about because government didn’t borrow in the hard times? A myth — but if enough people believe it, it can justify a government embarking on ruinous debt binge now. When

David Cameron was tracing the world’s ills

to British colonialists the other day, those who have read Ferguson’s Empire would be

well-armed to know the extent to which the British empire was a force for good in the world. My point: that history books are surprisingly useful in helping understand day-to-day events. And

Ferguson’s books especially so.

The last episode of Niall Ferguson’s documentary series, Civilization,

has just been aired — and for those who missed it, it’s time to buy the

DVD box set. Or, better still, read

the book. Ferguson is, for my money, one of the most compelling, readable and original historians writing today. His books stand out for throwaway lines which can change the way you think about

what’s happening now. Understanding of history shapes our politics, whether we admit it or not. And myths about history also fuel political myths. How often do we hear it said that the Great

Depression came about because government didn’t borrow in the hard times? A myth — but if enough people believe it, it can justify a government embarking on ruinous debt binge now. When

David Cameron was tracing the world’s ills

to British colonialists the other day, those who have read Ferguson’s Empire would be

well-armed to know the extent to which the British empire was a force for good in the world. My point: that history books are surprisingly useful in helping understand day-to-day events. And

Ferguson’s books especially so.

The more popular Ferguson becomes, the more stick he gets. I’m not surprised. His work is intellectual Kryptonite to the lazier leftist presumptions. His series this time is about how

‘the market’ — or, more accurately, voluntary human co-operation — created Western civilization. And how big government (with its big debt and welfare) now threatens it. He

looks at six devices which he says created Western civilization: competition, science, property rights/democracy, medicine, the consumer society and the work ethic.

I suspect he now regrets calling them ‘killer Apps’, a device used to divide up his thesis into television chapters — but which provided ammo for his critics. Milton

Friedman’s Free to Choose was a

book accompanying a TV show, and did not suffer because of it. Ferguson’s Civilization is firmly in this

tradition. His critics may well say that the ideas he mentions are explored more fully in other books, but it’s intended as an argument — and he pulls off his thesis with brio. It

challenges what you think you knew about Western history, and invites awkward questions about our future.

I shan’t attempt to summarise the book here. But below are some of the passages and arguments which jumped out at me. I suspect the points won’t be new to many CoffeeHousers, but others

may find them interesting:

— By comparison with the Yangtze, the Thames in the early 15th century was a veritable backwater. Within less than a century of the Forbidden City’s construction between 1406 and 1420,

the relative decline of the East may be said to have begun.

— Why did the Europeans seem to have so much more commercial fervour than the Chinese? The answer lies in maps of medieval Europe which show hundreds of competing states. There were roughly 1,000 polities in 14th century Europe.

— Why did Britain industrialise first? Labour was significantly dearer (at one point London real wages were six times those in Milan), so it made better sense in Britain than anywhere else to replace expensive men with machines fuelled by cheap coal.

— The revolutions of 1830 and 1848 were the results of short-run spikes in food prices and financial crises more than social polarisation.

— Europeans are today the idlers of the world. 54 per cent of Belgians and Greeks aged over 15 participate in the labour force, compared with 65 per cent of Americans and 74 per cent of Chinese.

— Mass immigration is not necessarily the solvent of a civilisation. Between 1999 and 2009 a total of 119 individuals were found guilty of Islamism-related terrorist offences in the UK, more than two-thirds of them British.

— He quotes a scholar from the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences “We were asked to look into what accounted for … the success, in fact, the pre-eminence of the West all over the world. We studied everything we could from the historical, political, economic, and cultural perspective. At first we thought it was because you had more powerful guns than we had. Then we thought it was because you had the best political system. Next we focused on your economic system. But in the past 20 years we have realised that the heart of your culture is your religion. Christianity.”

— Britain is already one of the most godless societies in the world, with 56 per cent never attending church at all, the second highest rate in Western Europe.

— Collapse can be sudden. Japan’s empire reached its maximum territorial extent in 1942, after Pearl Harbour. By 1945 it was no more. The UK’s age of hegemony was effectively over less than a dozen years after its victories over Germany and Japan.

— Many Asian powers, notably India, wasted decades on the erroneous premise that the socialist institutions pioneered in the Soviet Union were superior to the market-based institutions of the United States.

— The financial crisis of 2007 should be understood as an accelerator of an already well-established trend of relative Western decline.

— Japan has been able to increase government debt without triggering a crisis of confidence. But almost all Japanese debt is in the hands of Japanese investors and institutions, whereas half the US federal debt in public hands is in the hands of foreign creditors. [NB, the UK does not release our figures].

— [On Huntingdon’s Clash of Civilizations] Of 30 major armed conflicts either still going on or that had recently ended in 2005, twelve years after the publication of Huntingdon’s essay, 19 were essentially ethnic [ie, civil] conflicts.

— More cars are now bought in China than in America. In 2007, China overtook Germany in terms of the number of new patent applications, having overtaken Britain in 2004, Russia in 2005 and France in 2006.

— Many Europeans today will say religious faith is just an anachronism, a vestige of a medieval superstition. They will roll they eyes at the religious zeal of the American Bible Belt, not realising that it is their own lack of faith that is the anomaly.

And his sign-off sums up his argument:

Today, the biggest threat to Western civilization is posed not by other civilizations but by our own pusillanimity — and by the historical ignorance that feeds it.

Comments