What is wrong with Peter Grimes, the central figure of Britten’s eponymous opera? Or should the question be: what is wrong with Peter Grimes? For though there is no question that the opera makes a powerful and disturbing impression in a decent performance, it turns out always to be rather difficult to locate the focus of the work.

What is wrong with Peter Grimes, the central figure of Britten’s eponymous opera? Or should the question be: what is wrong with Peter Grimes? For though there is no question that the opera makes a powerful and disturbing impression in a decent performance, it turns out always to be rather difficult to locate the focus of the work.

In the revival at the Royal Opera of Willy Decker’s production, revived by François de Carpentries, there is minimal characterisation of the minor figures in the drama, though the cast-list is a starry one, and the mainly black and white staging of John Macfarlane does seem to endorse Britten’s claim that he had tried ‘to express [his] awareness of the perpetual struggle of men and women whose livelihood depends on the sea’. Yet while Britten’s music never allows us to forget the elements, and the dependence of most things that happen to the characters on the weather and the sea, it seems to be at least as much about the turmoil within Grimes and the problems that the anfractuosities of his nature create with all his relationships.

Adrian Mourby, the ubiquitous contributor of operatic programme notes, suggests that Grimes is lacking in ‘the necessary social skills’, and while it may be that the Borough would be improved by having a psychiatric social worker among its members, who could sort out that kind of problem, somehow it seems to me that the issue goes beyond that into a more intractable realm. That, certainly, is what the music suggests. In the very opening, the lawyer Swallow’s rapid declaiming of the oath that Grimes has to take in the witness box is contrasted with the soft, slow dreamy repetitions of his words by Grimes, and immediately we know that we are confronted by a harsh practical person, representative of his hard-pressed community, and a solitary dreamer, who has to be brought down, or round, by the other members of the community. That is the first big nudge we get to sympathise with Grimes, and as the Prologue develops we are led to feel that Grimes’s problem is that, like Hamlet, he has that within that passes show, Ellen Orford being the only person who realises that.

On the other hand, Grimes can be not only articulate but also positively poetic, as his monologue after he has entered The Boar reveals: ‘Now the Great Bear and Pleiades’, so he is not tongue-tied like Billy Budd. I’m inclined to think that Britten and his librettist Montague Slater were content to let him remain a mysterious figure, so that members of an audience could unload on to him whichever variety of existential Angst they were feeling at the time; and in that way the opera does still work.

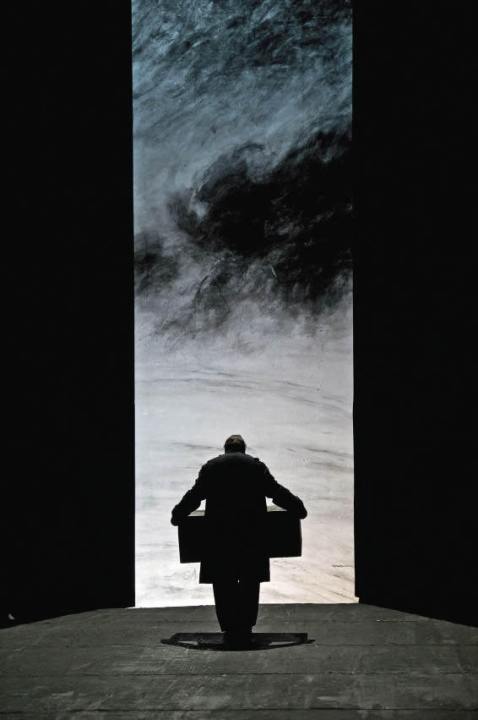

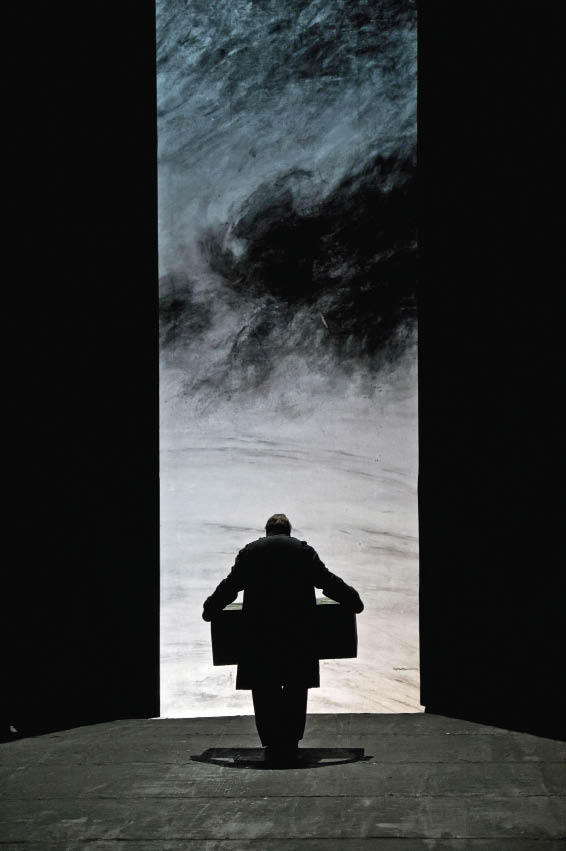

Each production of it that I have seen has put a different slant on that central problem, some making us identify with Grimes as strongly as possible all the way through, though that does lead to some awkward places; while others leave an area of vagueness. The latter is very much the case with Decker’s production, and the more so with Ben Heppner’s portrayal. In the fifth performance, which I saw, Heppner was in mainly good voice, with only a few unnerving places where he lost pitch and tone, though when that happens it is alarming. He doesn’t do much more, though, than stagger round the stage like a wounded creature, so one’s feelings about him remain simple.

Amanda Roocroft, as Ellen Orford, made less than I had hoped of the part. It isn’t a strongly delineated role, and Roocroft seemed content to sing it decently, if without much volume, but without bringing out the strength of the character, which ought to lead one to feel that things might have gone differently and that she could have brought Grimes happiness.

The townsfolk, who are presented singing their hymns with the hymn sheets covering their faces, are not much more than a lynch mob. The Boar is inhabited by a collection of caricatures, so that, for example, Mars Sedley, intent on getting her laudanum, but also a sinister mischief-maker, is nothing more than a croaky scurryer in Jane Henschel’s performance — and surely Britten wanted every role sung. Again, Auntie and the Nieces go for nothing, strongly cast as they are. And since almost the whole stage is used throughout, the contrast of indoors and outdoors is minimised, to especially damaging effect. Even so brilliant a singing actor as Roderick Williams, who made such an impact as Ned Keene in Opera North’s production, made little of the same role here.

Despite all of which, the evening was a memorable one, because Andrew Davis’s conducting was of staggering power. And the orchestra, which has played impressively all season, reached extraordinary pitches of detailed intensity. I felt more certain than ever that Britten never again produced so rich and musically inexhaustible a score, nor one that sounds as fresh now as it did 66 years ago.

Ben Heppner as Peter Grimes in the Royal Opera production

Comments