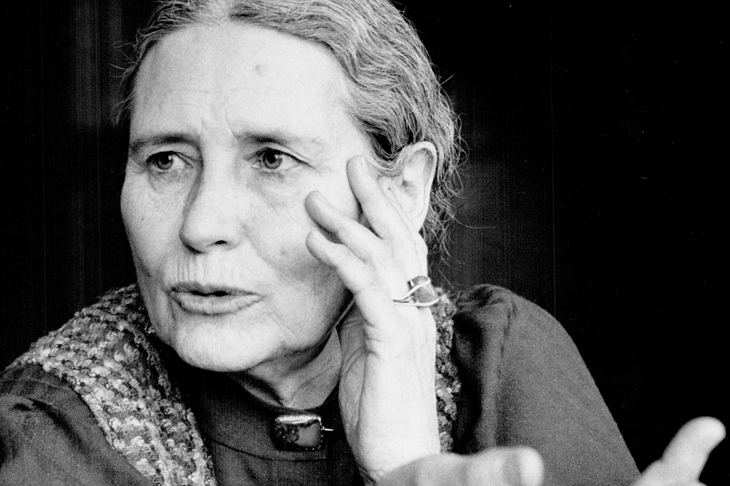

‘I am interested only in stretching myself, in living as fully as I can.’ Lara Feigel begins her thoughtful book with this assertion by Anna Wulf, the protagonist of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, and it rather sums up the whole endeavour of the volume. Feigel weaves close readings of Lessing’s prose, both fiction and non-fiction, with accounts of her own self-stretching.

Feigel, an academic, had read Lessing as an undergraduate, but, returning to her in her thirties, she discovered in the books a stimulating discussion about ‘how as a woman to reconcile your need to be desired by men with your wish for sexual equality’. She is particularly interested in the way Lessing ‘placed sexual fulfilment at the centre of women’s lives’.

There are big questions here. Lessing, says Feigel, ‘had allowed me to see my own sense of the inextricable nature of body and mind, of the personal and political, as the basis for thinking about life’. She follows Lessing geographically — to Zimbabwe, for example — and in her pursuits, including ‘brushes with adultery’ and psychoanalysis. (Ronnie Laing naturally steps on stage.) In Los Angeles, Feigel interviews Clancy Sigal, with whom Lessing had a serious love affair. He once said, ‘compared to her writing, cooking was her real genius’. Philip Glass, with whom Lessing worked and on whom she had an unrequited crush, refuses to meet the author. So she goes to hear one of his operas instead.

Feigel ranges over the prose, the letters and diaries (many in a Sussex archive), and the life of her prey. Descriptions of the farm in the Banket District of the maize-growing region of Lomagundi where Lessing grew up in what was then Southern Rhodesia are wonderfully evocative. Feigel understands the importance of specificity: we hear Lessing’s father’s wooden leg banging as he climbs up and down mine shafts in a futile attempt to find gold on his land.

She examines how Lessing ferried ideas about how to be a free woman into her fiction. Other writers pop up, notably D.H. Lawrence, though concerning identity rather than being a woman.Through it all Feigel reflects Lessing’s ideas back on herself. ‘In order to be truthful,’ she writes, ‘and therefore in order to be free, I had to expose, both in person and in print, the side of me that was dislikeable.’ That is brave.

The arrangement of material is roughly chronological, from Lessing’s childhood, through two marriages, the move to London in 1949, communism, a 30-year dalliance with Free Love (Lessing said she liked ‘flitting from flower to flower’), Sufism and the post-menopause adoption of an identity of asexual frump with a bun. I only knew Lessing personally in that latter role and, reading this book, I’m sorry I missed the earlier years. Then, of course, the call from Stockholm. Regarding the communist interlude, Lessing reluctantly left the Party after Hungary, but she didn’t give up on it altogether for several years.

There is much debate over her famous decision to abandon her first two children. Feigel is even-handed, citing all that Winnicottian nonsense about ‘maternal ambivalence’ (the concept isn’t nonsense, but Winnicott’s opinions were). Is it wrong, she asks, ‘for writers to claim a special privilege when it comes to maternal ambivalence?’ Yes, in my view, it is wrong, but Feigel does not trade in glib answers. Everything is this book is seriously handled. Through Lessing and other writers, for example, Feigel traces the evolution of attitudes to mothering.

Orgasms feature quite a bit. Some readers might feel less information would have been preferable. In discussing the slow disintegration of her own marriage, Feigel describes an episode when her husband withdraws from coitus at the crucial moment against her wishes because he doesn’t feel ready to have another child with her. Is this information for the public domain? Of course, she is following Lessing, who, in her autobiography and in her fiction, did not shrink from such details. Remember Anna Wulf describing her period at wearying length in The Golden Notebook?

Feigel’s previous books include The Bitter Taste of Victory, about love and art in the ruins of the German Reich. She is an accomplished writer, and able to acknowledge the ‘patchiness’ of Lessing’s prose, while freely admitting that her relationship with the novelist has amounted to an ‘obsession’. Free Woman is not a biography, but the same artistic process is at work: as a biographer, you think you are going to possess your subject, but they always end up possessing you. It’s fertile ground, and Feigel a fine explorer. I really enjoyed this book.

Comments