To review some new books about Shakespeare is not to note a revival of interest, but simply to let down a bucket into an undammed river. No one really knows the scale of the secondary bibliography. Published sources on any given topic in Shakespeare studies are innumerable and, as James Shapiro reminds us, so are books devoted to the idea that the works were written by someone else.

There are two theories to account for why Shakespeare is still so enormously prevalent in cultural life nearly 400 years after he died. The first is the cynical one, that it suited the British empire, and Anglo-Saxon culture in general, to foist the values and standards of one of its own on the rest of the world. If the political history of the world had been different, it is argued, we would now be talking about the universal genius of Avveroes or Lady Murasaki. Different cultures have different literary values; those of Shakespeare, we are told, were backed up by an empire, an army and a great trading nation.

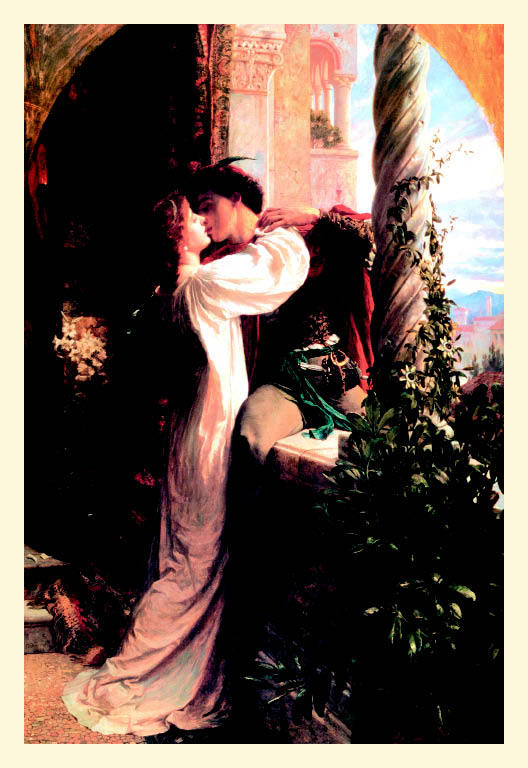

The second, less cynical, is convinced that there are, indeed, universal human values in Shakespeare which hardly any other writer has ever mastered on such a scale. We know exactly what deranged grief is like, equally from Hamlet as from our own experience; we listen to an explanation of first love, and marvel that it was so very much the same for a man in doublet and hose as for a spotty youth in a hoody. These universal significances override the undoubted fact that a good deal of Shakespeare’s poetry is now obscure to most of us, as some of it must always have been. There are passages in Coriolanus and other later plays which can never have been generally understood.

There is some truth in both of these ideas. Stanley Wells, the doyen of Shakespeare scholars, has produced the latest in a series of exceptional studies. Here he picks on the most enduring of human characteristics, one which we are most likely to recognise in ourselves and in works of the remote past: love and sex. It is certainly true that in Shakespeare’s writing on the subject we find a directly recognisable rendering of passion in ways that are not always true in other cultures. We flatter ourselves, too, in believing that we have passed through ages of prudery and bowdlerised editions, to return to a Shakespearean frankness on the subject. On the other hand, there are passages and beliefs in Shakespeare which seem bizarre to us, of which the cruxes of Measure for Measure and All’s Well that Ends Well are only the most notorious.

Wells steers a careful path between the multiple traps in this field. The much vexed question of same-sex attraction in the Sonnets, in Troilus and Cressida and Twelfth Night, among other places, gets a judicious response, making it clear how different these relationships were from anything we might recognise as homosexual in the modern sense. He has an excellent sense, too, not only of when Shakespeare is talking about sex, but when he is not. Shakespeare loved ingenious obscenity, clearly; when Mercutio talks about the ‘bawdy hand of the dial’ being ‘upon the prick of noon,’ it needs no actor’s gestures.

There are other moments when word-play seems to involve sexual meaning on some level, notoriously ‘Nothing’ in the title of Much Ado. But there are various modern guides who take the view that Shakespeare, through puns, wrote about almost nothing else. Wells has some fun with a couple of not very scholarly interpretations of Shakespeare designed to yield as much smut as possible for our puerile amusement. Shakespeare did not write in code, and Wells’s humane, flexible and sympathetic interpretation of, for instance, Romeo and Juliet, is as far removed from these sexually themed glossaries as can be imagined.

One of the most baffling features of Shakespearean bibliography is that sordid corner devoted to the proposition that William Shakespeare of Stratford did not write, and could not have written, the plays ascribed to him. James Shapiro’s Contested Will does not promote any of these obviously false claims, but documents the history of such suggestions.

The principal claimants are two. First, Francis Bacon, who was a very learned man, but not one obviously capable of the sort of stylistic flexibility and rugged poetry we find everywhere in Shakespeare. The Bacon claim was advanced most extensively by a 19th-century namesake, Delia Bacon. She and her followers became expert in a sort of self-serving cryptography, which saw Bacon’s signature in the texts of the plays and elsewhere, to the point of madness. There were ciphers in literature at the time and before, but all the ciphers discovered by the Baconians were beyond reasonable credibility.

At least Bacon was still alive when Shakespeare’s last plays were demonstrably being written, which is more than can be said of the other claimant Shapiro examines, the Earl of Oxford, who died in 1604. Astonishingly, the Oxford school seems to be gaining in strength at present. There are seminars, conferences and innumerable books, both pseudo- scholarly and fictional, devoted to the proposition that the Earl of Oxford wrote the canon. It was first put forward by a man called John Thomas Looney.

I find the Oxford claim the more objectionable, resting on the idea that Shakespeare was just too common to write the plays as we have them. It suggests that, set as they are mostly abroad, they must have been written by a well-travelled man, that they are full of learned allusions to the most recondite literature, and exhibit a kind of familiarity with court manners which only a peer of the realm could have mastered. We know, from a surprising amount of documentary evidence, about Shakespeare’s business affairs, some legal dealings and property matters, none of which indicates that he was anything but hard-headed, and almost none of which suggests the poet in everyday life.

This is all complete rubbish, of course. The plays may ostensibly be set often in Italy, but they have no idea that there are canals in Venice, for instance, and they believe that you get from Verona to Milan by ship. Bohemia has a sea-coast; the Viennese are called Angelo and Mariana. Far from being full of recondite allusions, they follow a number of popular books, such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses, largely to the exclusion of much other classical literature. Shakespeare obviously lost nothing at all by being an enthusiastic but a patchy reader, though he did not know some surprising things — that there were no clocks or billiards in ancient Rome, for example.

Moreover, even if he displayed the kind of learning and worldly experience ascribed by the Oxfordians to the canon, it would not mean that the plays must have been written by a rich nobleman. Ben Jonson, the stepson and, initially, apprentice to a bricklayer, wrote plays and masques more learned than anything Shakespeare ever wrote, including one, in Volpone, showing some acquaintance with Venetian institutions. No one, as far as I know, has ever doubted his authorship.

I wish I could think that the case for the Earl of Oxford rested on anything but snobbery and a lack of faith in the possibilities of the human imagination. The Oxfordians, as entertainingly described in Shapiro’s study for the purposes of dismissal, are a sad lot. It is truly astonishing that they, and the Baconians, have recruited some otherwise very intelligent people, from Mark Twain to Mark Rylance.

But you can’t altogether blame them. Reading Robert Winder’s new novel, The Final Act of Mr Shakespeare, we can perceive the same urge that drives the Shakespeare sceptics; the urge to stand behind that amazingly unimpressive head, and wonder how on earth anyone ever came to know any of that. Winder’s novel is not the first, and it will not be the last, to come up with solutions

to the mysteries of Shakespeare’s career, though I personally don’t believe that the Sonnets’ dedication to ‘Mr W. H.’ could possibly be a self-dedication to Shakespeare’s ‘most secret’ pseudonym, William Hathaway. The novel is not without its ludicrous aspects:

‘I can’t see it catching on,’ said Shakespeare. ‘Though I did wonder once about setting Macbeth to music …’

And Winder must be commended for boldly writing an entire mock-Shakespearean play, Henry VII, which, alas, like all mock- Shakespearean plays, sounds precisely like the one in Max Beerbohm’s short story ‘Savonarola Brown’:

What means he by this gift? What would he

have

That his commandment could not have more

cheap?

I fear some stealth in this. Who are you, sir?

The urge which seeks to reconstruct the unimaginable origins of the canon in novelistic or filmic form, and the one which finds it necessary to discover a new author for it are, I think, one and the same. We are never going to get to the end of it, apparently.

Comments