Fra Angelico (1395–1455), Il Beato (‘the Blessed One’) to his contemporaries as well as to John Paul II, who beatified him in 1982, is probably best known today for his frescoes in Florence’s San Marco, the Dominican convent where he lived as a monk. Perhaps fearing that some art-lovers will question the wisdom of mounting a Fra Angelico exhibition without the San Marco frescoes, the show’s curators have included a video of them. They need not have worried. Even without the frescoes, the 25 Fra Angelicos at the Musée Jacquemart-André, together with a well-chosen assortment of pictures by the friar’s colleagues working in the same religious vein, are more than enough to make this a rich exhibition.

The art created in the Florence of Fra Angelico was a bridge between the International Gothic as practised by Fra Angelico’s master and fellow monk, Lorenzo Monaco (c.1370–1424), and the dawning Renaissance exemplified by painters such as Masaccio and Masolino, whose ‘Saint Julian’ (1423–5) and ‘The Story of Saint Julian the Hospitaller’ (1427–30) appear in this exhibition. The daring young Florentine painters of the first half of the early Renaissance were picking up where Giotto had left off a century earlier, depicting the human body in a much more realistic fashion and paying detailed attention to nature and to the rules of perspective. The way Fra Angelico absorbed these new ideas while still maintaining much of the stylised elegance of the International Gothic showed nothing less than genius.

The exhibition allows us to grasp this by making comparisons between Fra Angelico’s work and one of the show’s highlights, Lorenzo Monaco’s c.1424 ‘Saint Nicholas Saving the Sailors’. Here we see the beleaguered sailors being rescued by the saint in a sea that looks like a greenish wig, its curls symbolising the water’s waves. Contrast that with Fra Angelico’s splendid ‘Episodes from the Life of St Nicholas: Birth, Vocation and Gift to Three Poor Young Girls’ (c.1427), and note the artist’s careful detail in his depiction of nature and the clothing in fashion at the time.

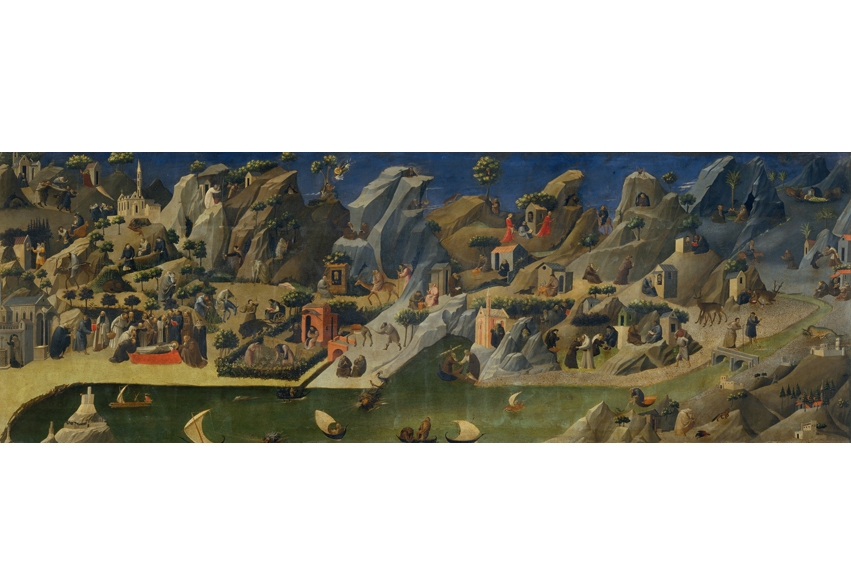

There is a lot of fun to be had here, too. ‘Thebaid’, painted by Fra Angelico early in his career in 1420, is one of a pair of pictures that might fascinate children as they spot lions, a bear standing on his hind legs, hermits sawing wood and a monk peering out from a tree. The paintings are set in the first century, when hermits and anchorites took refuge from Roman persecution in northern Egypt. Fra Angelico makes it look idyllic.

Paolo Uccello’s ‘St George and the Dragon’ (c.1440) is here, too, 30 years before the National Gallery’s version of the same story. No 15th-century Florentine artist was more assiduous than Uccello in studying perspective. An anecdote reveals that he was so fascinated by perspective that he would have stayed up all night exploring the technique had his wife not called him to bed, with him still murmuring, ‘Marvellous, this perspective!’ as he reluctantly left his desk. ‘St George and the Dragon’ allows us to enjoy not only Uccello’s mastery of perspective but also his skill in painting animals.

Even some grown-ups may grow a bit restless in the exhibition’s last sections devoted to the ‘Masters of the Light’ and what the curators have rather arbitrarily deemed ‘Fra Angelico’s Masterpieces’. ‘The Light’ comes from the golden glow that Fra Angelico and his followers used to represent God’s heavenly radiance, something that may explain why 15th-century Italian painters invariably portrayed the Virgin Mary as fair-haired. Some Renaissance painters were, however, more capable than others: Alesso Baldovinetti’s ‘Sacred Conversation’ (c.1466) is rather better than Zanobi Strozzi’s ‘Madonna of Humility with Two Musician Angels’ (c.1448–50), in which the musicians look like 1960s pop stars on cannabis.

I question whether several of the pictures in the exhibition’s first half are lesser masterpieces than the more solemn pictures (which look a little too much like illustrations in a catechism) at the end. No matter. Any opportunity to spend an hour or two enjoying the pictures of Fra Angelico and his contemporaries is not to be missed.

Comments