In July 1990, Nicholas Ridley told Dominic Lawson that monetary union was “all

a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe”. He was immediately forced to resign from the Cabinet. In this week’s magazine, which hits newsstands today, Lawson says that Nicholas Ridley was right (subscribers click here). Here, in full, is the article that ended his career:

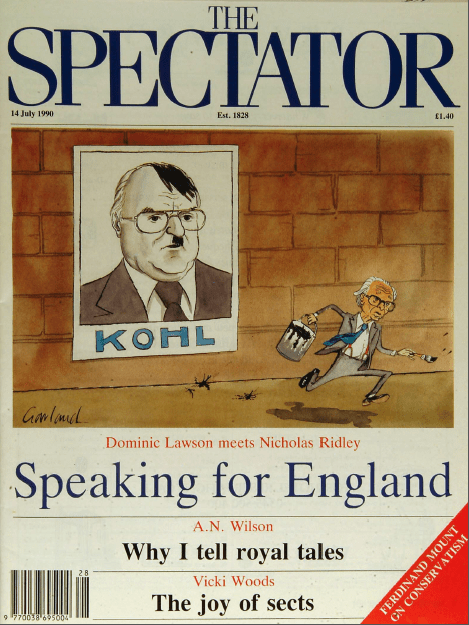

Saying the unsayable about the Germans, Dominic Lawson, 14 July 1990

It is said, or it ought to have been said, that every Conservative Cabinet minister dreams of dictating a leader to the Daily Telegraph. Nicholas Ridley, the Secretary of State fro Industry is, so far as I am aware, the only one to have done so. It happened when the late Jock Bruce-Gardyne, long-time writer of the Telegraph’s economics leaders, was staying with Mr Ridley. The then deputy editor of the Telegraph, Colin Welch, rang up to urge Jock to file a promised leader for the next morning’s paper.

Colin Welch: Is that Jock?

N. Ridley: Yes.

CW: Where is your leader? We need it now.

NR: Right oh!

CW: I’ll put you on to the copytackers.

At which point Ridley delivered an impromptu pastiche of a Bruce-Gardyne leader, unfortunately too sureal to pass Mr Welch once he read it and divined its true author.

After I had visited Mr Ridley in his liar, an 18th-century rectory in the heart of his Gloucestershire constituency, I could see why he should delight in such innocent deception. As we ate lunch together I stared through what I had thought was a window behind my host’s left shoulder. But it was in fact a magnificent trompe l’oeil, painted by Mr Ridley in 1961.

The house’s – real – garden, designed by Mr Ridley, a civil engineer by training, is similarly baffling. One secluded section turns cunningly into another, and from any one fixed position it is impossible to see where the next turn might lead.

But Nicholas Ridley’s passion for illusion is most definitely only a pastime. In modern political life there is no more brutal practitioner of the home truth. Not even Mrs Thatcher – whose own views owe much to his – is more averse to hiding the hard facts behind a patina of sympathy or politician’s charm. In a mirror world Mr Nicholas Ridley would be Mr Cecil Parkinson.

Even knowing this, I was still taken aback by the vehemence of Mr Ridley’s views on the matter of Europe, and in particular the role of Germany. It had seemed a topical way to engage his thoughts, since the day after we met, Herr Klaus-Otto Pohl, the president of the Bundesbank, was visiting England to preach the joys of a joint European monetary policy.

‘This is all a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe. It has to be thwarted. This rushed take-over by the Germans on the worst possible basis, with the French behaving like poodles to the Germans, is absolutely intolerable.’

‘Excuse me, but in what way are moves toward monetary union “The Germans trying to take over the whole of Europe”?’

‘The deutschmark is always going to be the strongest currency, because of their habits.’

‘But Mr Ridley, it’s surely not axiomatic that the German currency will always be the strongest…?’

‘It’s because of the Germans.’

‘But the European Community is not just the Germans.’

Mr Ridley turned his fire – he was, as usual, smoking heavily – on to the organisation as a whole.

‘When I look at the institutions to which it is proposed that sovereignty is to be handed over, I’m aghast. Seventeen unelected reject politicians’ – that includes you, Sir Leon – ‘with no accountability to anybody, who are not responsible for raising taxes, just spending money, who are pandered to by a supine parliament which also is not responsible for raising taxes, already behaving with an arrogance I find breathtaking – the idea that one says, “OK, we’ll give this lot our sovereignty” is unacceptable to me. I’m not against giving up sovereignty in principle, but not to this lot. You might just as well give it to Adolf Hitler, frankly.’

We were back to Germany again, and I was still the devil’s – if not Hitler’s – advocate.

‘But Hitler was elected.’

‘Well he was, at least he was… but I didn’t agree with him – but that’s another matter.’

‘But surely Herr Kohl is preferable to Herr Hitler. He’s not going to bomb us, after all.’

‘I’m not sure I wouldn’t rather have…’ – I thought for one giddy moment, as Mr Ridley paused to snub out his nth cigarette, that he would mention the name of the last Chancellor of a united Germany – ‘er… the shelters and the chance to fight back, than simply being taken over by… economics. He’ll soon be coming here and trying to say that this is what we should do on the banking front and this is what our taxes should be. I mean, he’ll soon be trying to take over everything.’

Somehow I imagined (and I admit it, because Mr Ridley is for ever accusing journalists of making things up) that I could hear a woman’s voice with the very faintest hint of Lincolnshire, saying ‘Yes, Nick, that’s right, they are trying to take over everything.’ I can at least recall, with no recourse to imagination, the account of one of the Prime Minister’s former advisers, of how he arrived for a meeting with Mrs Thatcher in a German car. ‘What is that foreign car?’ she glowered.

‘It’s a Volkswagen,’ he replied, helpful as ever.

‘Don’t ever park something like that here again.’

The point is that Mr Ridley’s confidence in expressing his views on the German threat must owe a little something to the knowledge that they are not significantly different from those of the Prime Minister, who originially opposed German reunification, even though in public she is required not to be so indelicate as to draw comparisons between Herren Kohl and Hitler.

What the Prime Minister and Mr Ridley also have in common, which they do not share with many of their Cabinet colleagues, is that they are over 60. Next question, therefore, to Mr Ridley: ‘Aren’t your views coloured by the fact that you can remember the second world war?’ I could have sworn I saw a spasm of emotion cross Mr Ridley’s face. At any rate he answered the question while twisting

his head to stare out of the window:

‘Jolly good thing too. About time somebody said that. It was pretty nasty. Only two months ago I was in Auschwitz, Poland. Next week I’m in Czechoslovakia. You ask them what they think about the second world war. It’s useful to remember.’ It’s useful to know that Mr Ridley’s trips to Poland and Czechoslovakia are efforts, in the company of some of Britain’s leading businessmen, to persuade East Europeans of the virtues of doing business with Britain. How very annoying to see the large towels of Mr Kohl and his businessmen already covering those Eastern beaches.

But, hold on a minute, how relevant to us, now, is what Germany did to Eastern Europe in the war? Mr Ridley reverted to the sort of arguments he must have inhaled with his smoke when he was a minister of state at the Foreign Office:

‘We’ve always played the balance of power in Europe. It has always been Britain’s role to keep those various powers balanced, and never has it been more necessary than now, with Germany so uppity.’

‘But suppose we don’t have the balance of power: would the German economy run Europe?’

‘I don’t know about the German economy. It’s the German people. They’re already running most of the Community. I mean they pay half of the countries. Ireland gets 6 per cent of their gross domestic product this way. When’s Ireland going to stand up to the Germans?’

The strange thing about Mr Ridley’s hostility to the Bundesbank and all its works is that, if he had ever been Chancellor of the Excehquer – a job he admitted to me he had once coveted, but no longer – then he would probably have matched the Germans in his remorseless aversion to inflation. But as he pointed out, ‘I don’t think that’s relevant. The point is that when it comes to “Shall we apply more squeeze to the economy or shall we let up a bit?” this is essentially about political accountability. The way I put it is this: can you imagine me going to Jarrow in

1930 and saying, “Look boys, there’s a general election coming up, I know half of you are unemployed and starving and the soup kitchen’s down the road. But we’re not going to talk about these things, because they’re for Herr Pohl and the Bundesbank. It’s his fault; he controls that; if you want to protest about that, you’d better get on to Herr Pohl”?’

There might be more financial discipline in a British economy run under the influence of men like Herr Pohl, Mr Ridley agreed. But, he added, suddenly looking at me through his bifocals, ‘There could also be a bloody revolution. You can’t change the British people for the better by saying, “Herr Pohl says you can’t do that.” They’d say, “You know what they can do with your bloody Herr Pohl”. I mean. You don’t understand the British people if you don’t understand this point about them. They can be dared; they can be moved. But being bossed by a German – it would cause absolute mayhem in this country, and rightly, I think.”

The rumbustious tone of Mr Ridley’s remarks and the fact that our conversation was post-prandial may give the misleading impression that the politician was relaxing, and not choosing his words too carefully. Far from it. Mr Ridley had the smallest glass of wine with his lunch, and then answered all my questions with a fierce frown of concentration, one hand clutched to his forehead, the other helping to provide frequent supplies of nicotine.

And although he has not been so outspoken on the matter of Europe before, it is no secret that Mr Ridley was a supporter of Enoch Powell long before Mrs Thatcher was ever a force in the political firmament. I reminded Mr Ridley that he had voted for Enoch Powell in the 1965 contest for the leadership of the Conservative Party, and asked him, ‘If Mr Powell had been elected and then become prime minister in 1970, would there ever have been a need for Margaret Thatcher?’

At this point, Mr Ridley’s frown of concentration became an angry scowl, and to aid his pondering further he removed his spectacles and poked himself in the eyes with the ear-pieces.

‘I think that it is possible… right. But then you have to put against that some extraordinarily correct but totally unreasonable belief that Enoch might have developed, which would have meant that his prime ministership would have been a failure.’

I must say that at this point I was overcome with admiration for Mr Ridley. Any other politician in the same position would either have said, to be safe,

‘Yes there would still have been a need for Margaret Thatcher’ or, less sycophantically, ‘I don’t think there’s much point in answering such a hypothetical question.’

Similarly, when I asked Mr Ridley how he felt, as a self-described ‘Thatcherite before Mrs Thatcher’, seeing old Heath-men like Kenneth Baker, Douglas Hurd and Christopher Patten gain greater preferment under the lady, he was quite unable to come up with the diplomatic evasion. Instead he produced an expression halfway between a smile and a grimace: ‘I don’t want to go into colleagues, and that. That’s getting close to what you put in your memoirs. I’m not going to say things about the current differences in the government because I think on the whole it’s a very good government. And of course everybody in it has slightly different views about things.’

‘Slightly?’

‘Well, less than slightly, but I’m not going to divulge those or talk about them.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because it would weaken the government.’

‘It might help to strengthen the government.’

‘Yes, but I’ll do that my own way, not your way.’

‘You think your way is successful?’

‘Oh yes, I’m quite happy.’

‘Does that mean you are still winning the important battles in Cabinet?’

‘That presupposes that there are battles. We’re moving pretty well along in the right direction. If I felt out of sorts with the whole thing I would resign. It’s not an idle threat.’

That certainly will be believed. Mr Ridley is still serenaded by the Right as the only minister to resign from the Department of Industry after Mr Heath’s famous U-turn of 1972. Mr Heath still insists that he sacked Mr Ridley. The truth – as usual in such matters – appears to lie somewhere in between.

Whatever, it seems that only Mrs Thatcher changing her views on Europe – a nearly incredible proposition – would cause Mr Ridley to leave the Department of Industry in such traumatic circumstances for a second time.

Or, as Nicholas Ridley put it to me with his habitual but constantly surprising and un-English directness, ‘I’ve been elected to Parliament nine times, I’ve been in office for 14 years, I’m still at the top of the political tree, and I’m not done yet.’

You can subscribe to The Spectator from just a £1 an issue.

Comments