File this double shot from the Spectator archives in the folder marked ‘For

historical interest’. Our leading article on the creation of the National Health Service in 1948, and an essay by Lord Moran from one week after:

File this double shot from the Spectator archives in the folder marked ‘For

historical interest’. Our leading article on the creation of the National Health Service in 1948, and an essay by Lord Moran from one week after:

Health and security, The Spectator, 2 July, 1948

July 5th, 1948, will be a notable date in British social history, marking as it does the entry into operation of the National Health Service and the National Insurance Acts. The latter removes from the whole of the population the fear of want, even though many will still be left in circumstances so straitened that the National Assistance Board, created to meet special cases in which the statutory National Insurance benefits are plainly insufficient, will have plenty of scope for its valuable and necessary activity. But the new National Insurance Act represents, after all, only an extension and rationalisation of a system with which the nation has been familiar for nearly forty years. The Health Service Act marks a totally new departure in the responsibility of the State for the physical welfare of its citizens. The case for a national health service in principle is overwhelming. The British Medical Association has recognised that as fully as anyone, whatever differences there may have been about scope and method. But it is particularly opportune that the new President of the B.M.A., Sir Lionel Whitby, should in his presidential address have fixed attention so firmly on the fundamental justification for the new service, the principle that health shall not depend on income, so far as timely and adequate medical treatment can secure health. “Changes in medical treatment,” said Sir Lionel, “have tended to increase the cost of treatment so much that most people can no longer afford to be ill.” That is profoundly true, but it promises to be true no longer. So far as money can buy health, no man henceforward need lack health for lack of means.

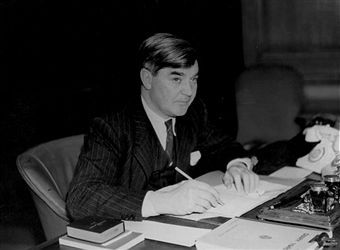

The fact that nearly 17,000 doctors have so far agreed to serve under the National Health Scheme must be regarded as satisfactory, in view of the controversies that have marked the discussions between the medical profession and the Minister of Health. No stress need be laid on these now. Mr Bevan went a long way towards meeting the doctors’ chief objections to the Act as originally drafted, and the doctors on their part showed wisdom and a sense of responsibility in reversing their previous decision to refuse service under the Act. Now a great experiment begins, in an atmosphere which the chief spokesmen of the B.M.A have by their public utterances tried to make as favourable as possible. No one doubts that many initial difficulties will present themselves. There are too few doctors for the anticipated demand; there are far too few nurses; the majority of dentists appear for the moment to be standing aloof from the scheme; the health centres, whose existence might so much ease the lot of doctors with insufficient surgery accommodation and equipment of their own, must wait till more labour and material is available in the building industry. But it is undoubtedly right to get the health service started. Whenever it was started it would be imperfect, and need to be amended and improved in the light of experience. That process may press rather heavily at times on both doctor and patient, and from the patient in particular at the outset full allowance for the doctor’s inevitable difficulties may reasonably be looked for. But the nation will soon possess the best medical service in the world.

A new health era, Lord Moran, The Spectator, 9 July, 1948

The Act which came into force on Monday is only the last phase of the work on the health services that has gone on for generations. But it was the war which, by rubbing the nation’s nose in the

facts, prepared it for reform, and educated many in the medical profession to accept change. Surveys of the hospital service of the country carried out during the war were disquieting. They had

shown that a third of the beds in municipal hospitals were in Public Assistance institutions, which often provided little more than food and shelter, and might have come from a novel by Charles

Dickens. It was intolerable that under the very shadow of the incomparably efficient teaching hospital there should shelter a Public Assistance institution which was a hospital only in name. There

should be one standard of hospital practice and one only. These surveys had shown, too, that a third of the beds in voluntary hospitals were in those which had less than a hundred beds, and with

notable exceptions were not in a position to bring their patients the resources of modern medicine and surgery. And all these hospitals had been planted anywhere without reference to the needs of

the community. Besides, there was not a single voluntary hospital which could say with certainty that, with the staggering rise in the cost of maintenance, it would be solvent in a year’s time. The

case for a reorganisation of the hospital service was overwhelming.

The case for the reformation of the general practitioner service was nothing like so strong, and from the first the majority of these doctors were bitterly hostile to the Act. They were particularly opposed to the Minister’s proposal that they should be paid partly by a basic salary. Mr Bevan argued that this would help the younger doctor starting in practice, before patients came to him. The young doctors answered unfeelingly that they did not want this help. The Minister stuck to his basic salary; the doctors grew more suspicious. Was the basic salary a token to the Labour party of hope deferred? Had the goal of a whole-time salaried service not been quite abandoned after all? However that might be, the reasons given by the doctors for their attitude proved very unconvincing to the public. Certainly there was nothing in them that seemed to justify an uncompromising struggle against an Act already on the statute book. The public was puzzled. There must be some other reason for the doctors’ intransigence. There was. The explanation of the deep-rooted hostility of the general practitioner to the Act lay in his dread that was only a first step towards a whole-time service. It meant a break with the past, a new way of life. He feared he would lose his independence. And it was only when the Minister promised to bring in an amending Act, making it more difficult to introduce a while-time salaried scheme, that his fears were mollified. So that the second plebiscite was quite a different story from the first.

If there was no real substance in the reasons given by practitioners for their hostility to the Act, there was a good deal more in their dread of a whole-time service than the public has been willing to concede. This brings me to the importance of incentives. I am fearful of the effect of the loss of the competitive stimulus in a whole-time service. Meanwhile the Spens Report has taken an imaginative step to keep the specialist on his toes. He will be rewarded according to the quality of his work. It is true that his salary up the age of 40, when he will receive £2,500, will depend only on seniority; but beyond that figure he can rise only by professional merit. One third of all specialists will be rewarded by salaries that depend upon outstanding proficiency in their work. There ought to be no danger of the specialist sitting back and just ticking over.

Is the same kind of inducement offered to the keen general practitioner? At present we must answer no, but I hope that answer is not final. It is true that, as he will be paid in proportion to the number of his patients, the more work he does the more he will earn. But we are encouraging the quantity rather than the quality of his work. A doctor may have 4,000 patients on his list and yet do his work in a slapdash, perfunctory manner. The quality of this new service may depend on finding an incentive to the general practitioner to give of his best. I stress this because his life has in late years lost some of its colour. His patients tend, when seriously ill, to seek admission to a hospital or a nursing home. They are snatched from his hands just when they have become of most professional interest. If keen and able men are not attracted in general practice, nothing can save the service. There is great need, as everywhere, for the pride of craftsmanship.

What will the new service mean to the public? – and by the public I mean every man, woman and child, the 47 million inhabitants of these islands and not just the 22 million who have been on the panel. They will get the services of a general practitioner and, when he is in doubt, of a specialist to give a second opinion. Moreover specialists will not be congregated in the great cities as in the past, for there will be decentralisation, so that the sparsely populated rural areas may benefit. The lady almoner will no longer ask what a hospital patient can pay, but only what he needs. Sick people will get a district nurse, a dentist, a midwife and medicines, and certain appliances such as a truss for the rupture, an elastic stocking for varicose veins, and spectacles when they are necessary. There will be a pathological and X-ray service, which ought to ensure earlier and more accurate diagnosis. And finally, the local authority will try to provide domestic help in the home in time of sickness.

To enumerate the benefits does not tell the whole story. It is something to get hospital treatment free, but it is much more that the whole population should have at its service only first-rate hospitals. In the past hospitals were a law unto themselves; in the future there will be no place for the second-rate. The Minister, who now owns all these institutions, has put the teaching hospitals in charge of Boards of Governors. All other hospitals are entrusted to Regional Hospital Boards. In making this separation the Minister has shown a notable reluctance to blunt the growing edge of medicine. It is a little unfortunate that this administrative distinction threatens to cloud the relations between the different groups. But this is a passing misunderstanding. All sizeable hospitals in the regions will be engaged in the future in post-graduate teaching. There will be no non-teaching hospitals of any consequence. Each member of their staffs will have to be recognised and approved by the university under which they are grouped, so that in this fashion the university will ultimately control the quality of the staffs. And it is the quality of a staff which ultimately determines the efficiency of a hospital. It was this which we had in mind when we pleaded that England and Wales should be divided into regions so planned that in each region the hospitals would come under the influence of a university. It must be a university service if it is to develop it full possibilities.

In addition, every region will undertake a survey, so that each hospital may confine its activities to those for which is it fitted. But it is particularly important that the Regional Hospital Board shall exercise its duty of watching over the expenditure of public money and of supervising the business arrangements of the service, without any lay interference in the professional work of the doctor. In the past, some municipal services have been backsliders in these respect, and, indeed, with the present constitution of local government and of the Civil Service this vital principle is often in danger.

What is the future of private practice? I could only answer that question if I knew whether the country would recover its prosperity, and whether the individual citizen will decide that he gains something tangible by seeing his doctor as a private patient. The facilities will not be changed. There will still be private wings attached to many hospitals; it remains to be seen what demand there is for these beds under the new conditions.

The Prime Minister has warned the public that the new Act will not bring the millennium. For some years we shall be short of hospital beds, of nurses and of specialists. And for a long time there is be few, if any, Health Centres. I look on this as a mishap. A medical student lives for six years or more in the bracing atmosphere of criticism and discussion of a teaching hospital, and then he qualifies and amy go out into the silence and intellectual isolation in which too many general practitioners, cut off from their kind, may wilt and rust as the years pass. The Health Centre brings together half-a-dozen or a dozen practitioners, so that they have their consulting rooms in one building and meet daily, when they can exchange views and help each other. If this system is spread over the country, it will, I think, be of incalculable benefit to the practice of our art.

The doctor has lived for his work. He has spent himself all day and perhaps half the night. Will that be true in ten years’ time? And will the profession continue to attract the same type of man in the future as it has done in the past? To these questions I have no satisfactory answer, but they will decide the fate of this service, for the well-being of a profession is ultimately dependent on its power to attract a due proportion of exceptional men and on the rank and file having their heart in their work. Nevertheless there are grounds for the faith of the Archbishop or York. “I am convinced,” he said, “that this Bill will prove by far the greatest social reform which has ever been passed by Parliament, and that it will bring health and happiness and security to millions in a way which no previous Acts of Parliament have ever done.”

Comments