Earlier this week we ran a blog post by our cartoon editor Michael Heath, marking the death of the Ronald Searle. As an accompaniment, here’s the interview that Harry Mount conducted with Searle for The Spectator two years ago:

‘I went into the war as a student and came out as an artist’, Harry Mount, The Spectator, 13 March 2010

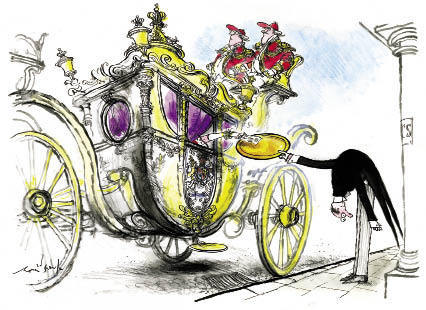

High in the mountains of Provence, in a low-ceilinged studio at the top of his teetering tower house, Ronald Searle is showing me the simple child’s pen he uses. As he draws the pen down the page, the ink thickens and swerves; a few sideways strokes, a little cross-hatching, and suddenly the famous Searle line comes to life: part Gothic, part anarchic, part comic. The girls of St Trinian’s, Nigel Molesworth, Adolf Eichmann, thousands of Punch caricatures, the Goya-like pictures of dying prisoners of war… all utterly different, all enclosed by that distinctive Ronald Searle line.

This month, Searle turned 90. Apart from a slight roughness to the voice, caused by a polyp on his vocal chord (‘The same as Julie Andrews — I’ll never sing “The Sound of Music” again either’), he is in fine fettle. His goatee beard is white but neatly trimmed; his high-collared white shirt and blue cardigan are immaculately pressed, his pale blue eyes hawk-like and always observing, observing.

And now, at last, Britain’s greatest cartoonist — and one of its great neglected artists — is receiving his due. Nick Garland, Gerald Scarfe, Posy Simmonds and Steve Bell have all expressed a deep debt to the master. Four new exhibitions are celebrating his birthday, at the Cartoon Museum, Maggs Brothers Rare Books and the Chris Beetles Gallery in London, and at the Wilhelm-Busch Museum in Hanover.

It is the German museum that will receive his complete works on his death. Searle has already handed them his archive, his sketchbooks since 1938 and his rare books and drawings — from Annibale Carracci to Rowlandson and Cruikshank. It is no less than Germany deserves for treating Searle as the serious artist he is. In France, too, he has been much admired; he drew a weekly political cartoon in Le Monde until 2007, when he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, the highest decoration the French state can bestow.

Meanwhile, over here, we go on treating cartoon art as the country cousin of the supposed proper stuff, keeping his work out of the National Portrait Gallery, denying him the knighthood he deserves.

Searle himself is too polite to say any of this. Left to his own devices, he prefers to talk of the necklaces designed by his devoted wife, Monica. He has lived with her in this tiny ancient Roman hamlet of Tourtour since 1966; and in France since 1961, when he left his two children and his first wife in London to set up home with Monica.

When pressed, though, he admits he’s pleased with these late-flowering accolades.

‘I’ve always felt that I was pigeonholed as the St Trinian’s chap. In among all this ghastly business of being 90, suddenly this generosity — from fellow cartoonists being so gracious with their praise — is absolutely lovely. It’s the first time in my life that I’m getting a reaction. I’ve always felt before that my work just dropped down a well, that I was working in a vacuum.’

It’s been a long time coming. Searle’s talent was spotted before the war, when he won a scholarship at Cambridge Art School in 1938, meaning he could give up working as a parcel-packer at the Co-op. His father was a porter on Cambridge Station. His mother came from a line of clockmakers, who painted the dials of the clocks.

‘That shows a slight artistic inclination,’ says Searle, ‘But otherwise my parents were what you might call very basic, terribly village Methodist. But they left me alone and let me go to Cambridge Art School for evening classes. Otherwise I just spent my whole time in the museums, in the Fitzwilliam, in the colleges — my grandfather was head porter at Peterhouse College, with the bowler hat and all that — just looking at things the whole time.’

At 14, he began collecting cartoons and books. Max Beerbohm and George Grosz were among early passions. His first cartoon was published in the Cambridge Daily News when he was 15; by 19 he was drawing for the Daily Express.

And then the war came, and the fates fell into place. First, while stationed in Kirkcudbright in 1940, Searle met two schoolgirls, evacuated from a school called St Trinnean’s, Edinburgh, a Scottish Gothic extravaganza of a building. ‘I prefer Renaissance architecture, but the gloom of Gothic suited my work better. I misspelt it by accident — St Trinnean was an ancient saint — and it stuck.’

The first St Trinian’s cartoon appeared in Lilliput magazine in October 1941. That month, Searle shipped out to Singapore. One month after his brigade arrived in Singapore in January 1942, the island was surrendered to the Japanese. Searle spent the rest of the war as a prisoner in Changi Prison and on the Thai-Burma Railway, made famous in The Bridge on the River Kwai. (‘The film’s rubbish,’ says Searle, ‘Alec [Guinness], who was a friend, hated it. The idea that you’d be proud of building a bridge as a prisoner was ludicrous.’)

Using the one pen that survived the boat trip from England, Searle made 400 secret drawings (several are in the Cartoon Museum show) of his fellow prisoners dying of cholera, and the brutalities meted out by the prison guards. One St Trinian’s cartoon was drawn on the back of a notice listing recent deaths in the prison. Another picture shows Searle holding a boulder in the air, while a leering guard stuck a sharp bamboo cane in his back.

‘The moment you dropped it, you got beaten up — and then they gave you a cigarette. I could never work out their mentality.

‘It all made me into an artist, though. I went into the war as an art student of 19, who did pictures of my mum and dad and the dog. Suddenly you’re drawing people who are going to die. With a subject matter so brutal, it was your duty to get something on paper that vaguely represented what was going on. I appointed myself an unofficial war artist. I developed far more as an artist in the four years I was in prison than in four years at art school.

‘The darkness in my drawings came from being a prisoner. When I came back, I couldn’t really do little maids laughing at foreigners any more.’

It was this darkness that set Searle apart after the war.

‘When he arrived on the scene in 1947, it’s very difficult for people of any younger generation to get a sense of how conservative the whole world was,’ says Nick Garland, the Telegraph cartoonist, ‘Along came Searle in Punch and Lilliput, and he brought something dark and jagged and outstanding; funny with a potential for savagery. He immediately became my hero. He got tagged with St Trinian’s — but even they were violent and delinquent and erotic; you quite often saw their knickers and stocking tops.’

It is still St Trinian’s that Searle is best known for. Even though he dropped an atom bomb on the school in 1953, the films keep coming out — the seventh, St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold, was released last year.

‘Like everything else I do, when it reaches its peak, and everyone adores it, you kill it off,’ says Searle. ‘But then the films appeared; and you simply can’t translate a sheet of paper into people. We haven’t seen the latest one, our DVD is on the blink. It’s made for 18-year-olds; how can you expect a 90-year-old to make any personal comment?’

Even after St Trinian’s had been bombed to smithereens, Searle’s publisher, Max Parrish, wanted more. Searle suggested an alternative. His friend Geoffrey Willans, of the BBC Foreign Service, had already written several skits on a boy’s prep school for Punch, and had suggested that Searle might do some illustrations. And so Nigel Molesworth, the curse of St Custard’s, ‘the goriller of 3B’, nemesis of Basil Fotherington-Thomas, was born.

‘Geoffrey and I just sat together in a room for hours, days on end, swapping ideas. He had been a schoolteacher, and had been to public school, I went to an elementary school. So he set up the framework but he gave me space to make it visual: to work out what animal the gerund would look like; how the Romans and the Gauls looked; the feel of the foopball ground, as Molesworth called it.’

Despite bewitching several generations with St Trinian’s and Molesworth, it is his reportage that Searle is most proud of, much of it in the Cartoon Museum show: sewer men and street sweepers in 1950s London, horse auctions and the funeral of George VI for the News Chronicle; commissions for the American magazines, Life and Holiday, including, in 1961, the newly built Berlin Wall and the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem.

‘Reportage is much harder, you’ve got to get behind what’s going on, to locate the atmosphere people are living in,’ he says, ‘Anyone can do a cartoon and make people laugh.’

Millions of devoted fans will disagree; no one can do it quite as well as the new nonagenarian.

Comments