John Knox, Cranmer complained, was ‘one of those unquiet spirits, which can like nothing but that is after their own fancy, and cease not to make trouble and disquietness’.

Yet this awkward cuss, son of a merchant in Haddington and initially a young Roman Catholic priest, became a pillar of the Reformation in Europe and the inspiration for Presbyterianism in Scotland. The recent Scottish political television debates remind us also that his strident tone is still fashionable in Scotland. The black and white judgments proclaimed rather than discussed, and the winning of arguments by out-shouting opponents, are exactly in the style of Knox.

He knew precisely what reforms were needed in the church. It was only necessary to follow the word of God: ‘add nothing to it; diminish nothing from it.’ The Bible did not prescribe vestments, the worship of saints, or sacraments other than baptism and communion. Such accretions were ‘idolatrie’.

The trouble was that almost everywhere the idolatrous Roman Catholic church (‘the synagogue of Satan’) was overwhelmingly powerful. In Knox’s lifetime Mary Tudor re-established Catholicism in England. Scotland was ruled by Mary of Guise and then by her daughter, Mary Queen of Scots, that ‘wicked woman’, widow of a French Catholic king. Huguenots were massacred in France. Knox himself was a galley-slave for 19 months after being captured by a French fleet off St Andrews. In Geneva and Frankfurt he was an exile and in both England and Scotland he lived in danger of arrest or worse — although, unlike his heroic mentor George Wishart, he was burned as a heretic only in effigy. Even at Knox’s death he remained deeply pessimistic about the very survival of the Reformation. To complain that he was ‘hatit and raillit on, but also perscutit most scharply, and huntit from place to place’ was no more than truth.

After six years in England, where he became a preacher to Edward VI and a lifelong anglophile, Knox fled from Bloody Mary’s England to Calvin’s Geneva. There he ministered to a highly able congregation of English and Scottish exiles, and helped them produce the foundation texts of Presbyterianism: the Book of Common Order, the Metrical Psalter and the Geneva Bible with its Protestant commentary. Geneva was for Knox ‘the maist perfit school of Christ’ where, better than anywhere else, manners and religion were ‘sinceirlie reformat’. It was the happiest time of his life, made even better when he was joined by his wife Marjorie Bowes, who was, as Calvin told him, ‘a rare find’.

Her mother eloped with her to continue her lengthy discussions on religion with Knox.

His First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (a title which everyone remembers) was the biggest mistake of Knox’s life. He never fully considered, or perhaps could not understand, the effect his violent strictures had on other people. The First Blast was aimed at Mary Tudor (‘that Jezebel’) and Mary of Guise, but he must have realised that their successors in ruling England and Scotland were likely also to be women — and women with whom the reformers would want to do business. Queen Elizabeth did not forgive Knox and distrusted as a result everything that came from Geneva.

When Mary returned from France to rule as Queen of Scots. Knox feared a rapid return to Catholicism. The exhausted 18-year-old, miserable at leaving France, arrived in Edinburgh, in August, in thick fog. This was symbolic, Knox warned, of what she was bringing to Scotland: ‘sorrow,dolour,darkness and all impiety’.He kept her awake that first night by having metrical psalms sung under her window accompanied by violins. Their famous interviews did not lead to a meeting of minds; Knox prayed publicly and regularly for the ‘blynde and obstinate Princesse’, and when she fled to England Knox criticised the Scottish nobility for the ‘foolish pity’ which prevented them from executing her when they had the chance.

Jane Dawson has pulled off the difficult trick of writing a scholarly book which is also a thoroughly good read. We have always known that Knox was a moralist, preacher and prophet on the grand scale. To hear him preach, according to the English ambassador, was ‘like having 500 trumpets blowing in one’s ears’.

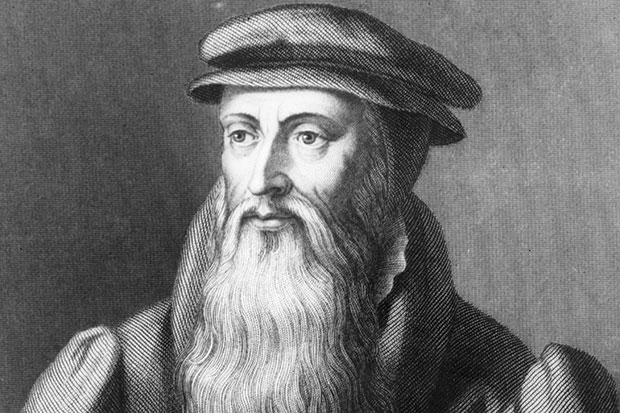

Dawson finds just enough, in some newly discovered letters and elsewhere, to suggest that he was also a complicated and sensitive man. Both his marriages were happy; members of his Geneva congregation printed a presentation copy of the Great Bible for him, and his periods of depression suggest that he agonised over the certainties he preached from the pulpit. The larger-than-life statue dominating the entrance to New College, in Edinburgh, has to be viewed alongside the unexpectedly vulnerable face in the posthumous portrait on the dustcover of this excellent biography.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £21.50 Tel: 08430 600033. Eric Anderson is a former Provost of Eton and rector of Lincoln College, Oxford.

Comments