What we’ve seen is a progression where — after the remarkable efforts which got the rates right down across the country — we first saw very small outbreaks, then we’ve seen more localised outbreaks which have got larger over time, particularly in the cities. Now what we’re seeing is a rate of increase across the great majority of the country.

It’s going at different rates, but it is now increasing. And what we found is anywhere that was falling is now beginning to rise and then the rate of that rise continues in an upward direction.

This is not someone else’s problem, this is all of our a problem.

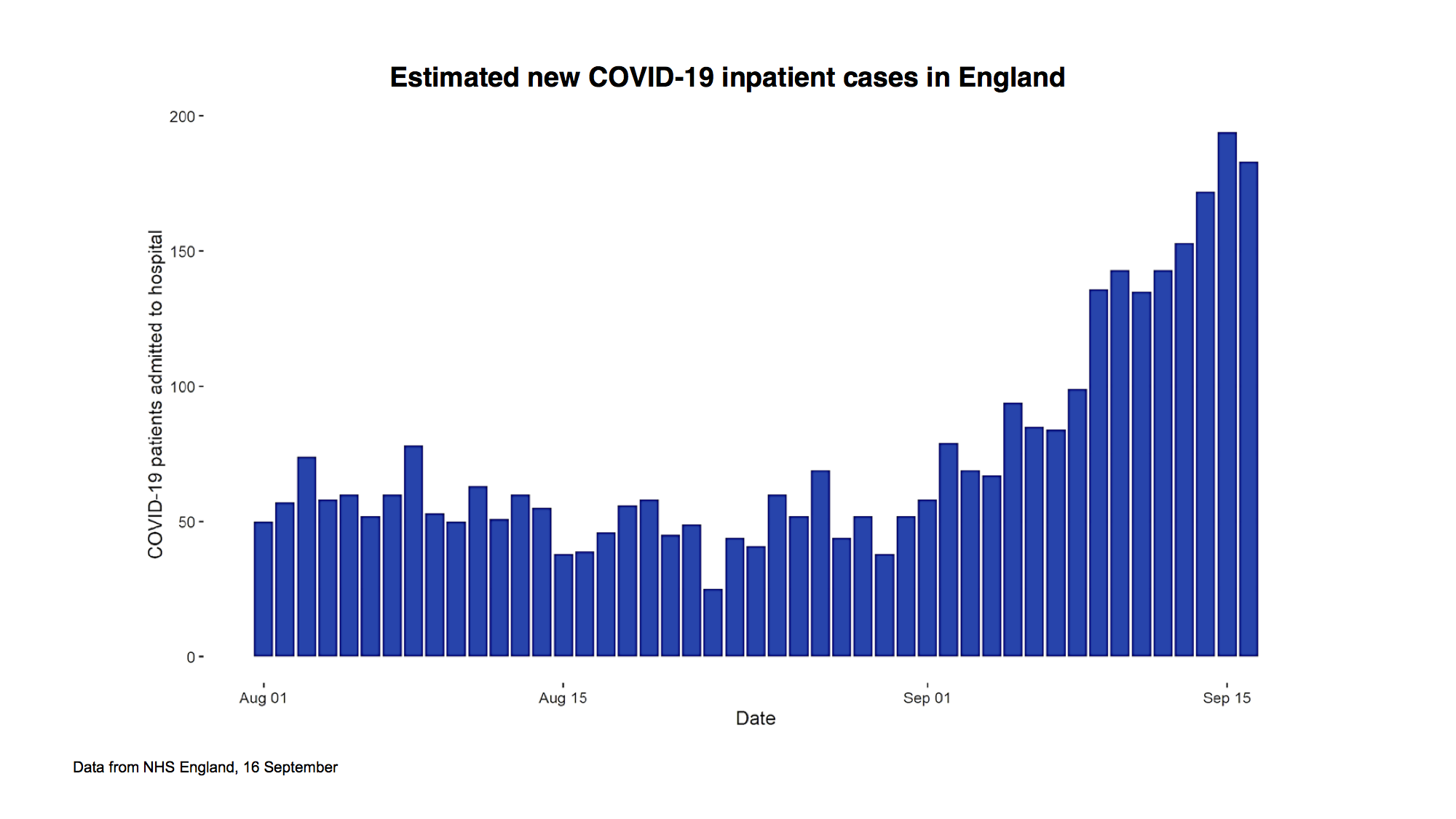

This graph is a simple one. It simply shows the number of inpatient cases in England over the period from 1 August. Until that point, there had been a steady fall over a long period of time, right back from early April.

It then stabilised for a period and flattened out. But over the period since 1 September, you can see a steady, sustained rise in numbers with a doubling time (as with the cases) of probably seven or eight days.

This is a six-month problem that we have to deal with collectively — it’s not indefinite

Now, what that tells us is that if this carried on unabated — and these numbers are relatively small, we’re talking about around 200 at the moment — but if this continued along that path, the number of deaths directly from Covid will continue to rise potentially on an exponential curve.

That means doubling and doubling and doubling again.

And you can quickly move from really quite small numbers to really very large numbers because of that exponential process. So we have, in a bad sense, literally turned a corner although only relatively recently. I think everybody will realise that at this point the seasons are against us. We’re now going into the seasons late autumn and winter, which benefit respiratory viruses. It is very likely they will benefit Covid as they do, for example, flu. So we should see this as a six-month problem that we have to deal with collectively.

It’s not indefinite. Science will, in due course, ride to our rescue. But in this period of the next six months, I think we have to realise that we have to collectively take this very seriously.

A lot of people have said maybe this is a milder virus than it was in April. I’m afraid, although that would be great if that were true, we see no evidence that is the case. At the moment, because the cases started to rise most in the lowest age bands in young adults, these are the group who are least likely to end up in hospital. A point we made right from the beginning is that for many people, this remains a mild infection. But as you move up the ages, if you move towards people who are more vulnerable then the mortality rates rise to quite significant rates.

What we’ve seen in other countries and are now clearly seeing here is that infections are not just staying in the younger age groups. They’re moving up the age bands. And the mortality rates will be similar to, slightly lower than they were previously, but they will be similar to what we saw previously. And these are significantly greater, for example, than ordinary seasonal flu. Seasonal flu normally in the UK would, during an average, year kill around 7,000 people, tragically, and in a bad flu year, as it was for example about three years ago, it might kill upward of 20,000 a year. This virus is more virulent than flu.

Treatment is better. There’s no doubt about that. Doctors and nurses have learnt to treat this much more effectively. And we have new drugs such as dexamethasone. These will reduce the mortality rate, but they will definitely not eliminate or take it right down to trivial levels.

There are two other broad points I wanted to make: the first one is that there are, as we’ve said from the beginning, four ways in which this virus is going to have a potentially very significant effect on the population’s health if we let it go out of control. The first is the easiest to identify and is direct Covid deaths: people who get the virus and die of the virus. The second is if the NHS emergency services were overwhelmed by a huge spike and that is what the extraordinary efforts of the population allowed to prevent from happening in the first wave. The third, however, is very important, and I think its importance should not be understated. If the NHS is having to spend a large proportion of its efforts trying to treat Covid cases, because the numbers have gone up to very high levels, it will lead to a reduction in treatment for other areas, in early diagnosis of disease and in prevention programmes. And so there is an indirect death effect on deaths and on illness from this impact on the NHS if we allow the numbers to rise too fast.

Finally, we also know that some of the things we have had to do are going to cause significant problems: in the economy; big social impacts; impacts on mental health. Therefore ministers making decisions and all of society will have to walk this very difficult balance. If we do too little, this virus will go out of control and we will get significant numbers of increased direct and indirect deaths. But if we go too far the other way, then we can cause damage to the economy, which can feed through to unemployment, to poverty, to deprivation, all of which have long term health effects. So we need always to keep these two sides in mind.

My final point is that a lot of people say: ‘If I increase my risk, well, can’t people just be allowed to take their own risk?’ The problem with a pandemic is if I, as an individual, increase my risk, I increase the risk to everyone around me and then everyone who’s a contact of theirs. And sooner or later, the chain will meet people who are vulnerable or elderly or have a long term problem from Covid. So you cannot, in an epidemic, just take your own risk. Unfortunately, you’re taking a risk on behalf of everybody else.

It is important that we see this as something we have to do collectively. There are broadly four things we can do over the next period to get on top of this. The first of which is reducing our individual risk. And this is around the things that we all know about: hands, face, space — washing hands, using masks (particularly in environments which are enclosed like public transport and so on) and also, in particular, having space between people whenever we can achieve it — especially when indoors.

The second is things we can do to isolate the virus. So if people have symptoms, they must self-isolate and we must find their contacts so that they can isolate. And in people who have travelled from high-risk areas, they also should isolate. This means that they are taking, on behalf of society, a big step forward to keep the virus out of circulation while they are still infectious. This is an absolutely critical part of the response.

The third, and in many ways the most difficult, is that we have to break unnecessary links between households. That is the way in which this virus is transmitted. And this means reducing social contact when at work. And this is where we have enormous gratitude for all the businesses who worked so hard to make their environments Covid secure to reduce the risk.

The final thing we can do is the science: investing in drugs, vaccines and diagnostics.

We have to try and deal with this in the least damaging way. But we all know we cannot do this without some significant downsides, and this is a balance of risk: if we don’t do enough then the virus will take off — at the moment, that is the path that we are clearly on. If we do not change course, then we are going to find ourselves in a very difficult problem.

Now listen to today’s Coffee House Shots podcast with Cindy Yu, Katy Balls and James Forsyth on the government’s scientific advice:

This is an edited transcript of Chris Whitty's comments during this morning's Downing Street press conference about the growing rate of Covid infections.

Comments