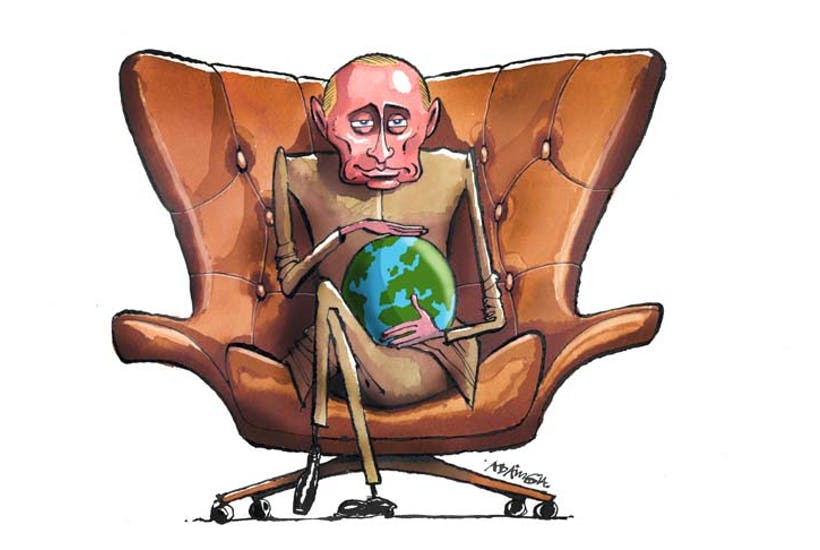

Gavin Williamson’s warning that the Russian Bear is sizing up the UK’s energy infrastructure is important as it brings long overdue attention to a troubling drift in UK energy policy.

Britain’s electricity market is increasingly slanted in favour of importing more electricity from Europe and against securing investment in new power plants at home. Billions of pounds of domestic energy plant investment have consequently been put at risk, which will undermine the future security of supply and risk price rises.

It is important to appreciate our growing reliance on imported electricity, as well as the fact that current planning will quadruple this dependency with consequences for prices, competition and security of supply. A new Centre for Policy Studies paper, ‘The Hidden Wiring’, follows months of research into proposals for more undersea cables to import electricity, called interconnectors, and details their negative impact on Britain’s electricity market.

Power imports from Europe increased by 52 per cent in the three years to 2016, and they are set to surge as more interconnectors are planned. Back in 2012, imports were expected to account for just six terawatt hours (TWh) of supply per year in 2030. But four years later, the projection has radically changed. The 2016 forecast sees Britain’s electricity imports rising from 21 TWh today, to a peak of 77 TWh in 2025. That’s close to a fifth of supply.

Importing electricity can bring advantages – ranging from price to abundant availability – but crucially these depend on a series of important factors. Our research shows that it is increasingly unlikely there will be much spare electricity in Europe to send to the UK in the future.

The truth is that Britain’s rising electricity imports are, in the short term, an easy way out of failed energy policies that stretch back over a generation. Back in 2012, the coalition had the right plans for a new fleet of domestic gas-fired plants that would be easy to switch on and off to accommodate the sporadic nature of weather dependent renewable supplies and boost security of supply. It estimated that Britain would need 26 GW of additional gas generation capacity by 2030 to plug any potential gap left by cloudy, windless days and to replace the electricity output from closing older coal, oil and nuclear plants. On current trends, however, the UK is on track to build just 12GW by 2030. This goes some way to explain the panicked dash to build interconnectors to import power.

Declining electricity supplies in Europe add to the problem. Both France and Germany are reducing their reliance on nuclear power (in Germany’s case, to zero by 2022) without any clear policy for replacements. Coupled with this is EU policy to combat climate change and air pollution; this will accelerate the shutdown of generating capacity across the continent. Europe still generates considerable electricity from coal and these plants are increasingly vulnerable to new legislation and political factors. A likely condition of Angela Merkel’s new coalition will be the closure of Germany’s dirtier coal plants. Holland is similarly keen to close all its coal plants over time with plans for a new carbon tax.

All of this means that importing power is likely to get more expensive, not less. And yet the way in which Britain allocates access for imports to the electricity grid continues to discourage building new gas plants as imports enjoy clear market benefits. This preferential access is undermining the investment case for new power plants in the UK through the Capacity Market, which holds its next auction for future power next week.

Interconnectors enjoy an unfair competitiveness boost too, because electricity generators in Europe don’t have to contend with Britain’s high carbon price floor tax – unlike UK generators. This means they can undercut British generators even if their power comes from dirty coal-fired capacity in Holland or Germany. So instead of cutting carbon emissions, the UK is in some cases simply offshoring it. Foreign supplies also don’t pay the transmission charges faced by UK generators.

Perhaps inadvertently, the Defence Secretary has highlighted both the vulnerability and growth of interconnectors. While they are particularly susceptible to accidents – such as in 2016 when a ship in the English Channel dragged its anchor over the link with France and halved supplies for months – their growth also undermines the investment case for vital new power stations at home, not to mention any potential for sabotage.

Energy security is a central plinth of national security. The Defence Secretary is right to flag up the risks for the UK as it becomes more dependent on imported power, but the priority must now be for energy ministers to explain why they are pushing these policies and why they think it is in Britain’s national, economic and security interest.

Tony Lodge is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Policy Studies and co-author of The Hidden Wiring – How electricity imports threaten Britain’s energy security

Comments