Strange, when your own life flatlines, the way in which other lives become suddenly more interesting. I have been retreating into biographies and memoirs as never before, scouring them for accounts of incarceration, illness, boredom, family meltdowns and sudden financial freefalls. One of the pleasures of the genre is the way in which the peaks and troughs of a lifetime are resolved by the author into a pattern as ordered as a heart rate on a hospital monitor: this year was a low point and this one a high point; this experience proved to be a turning point, while this one was no more than a blip in the chart.

For a graph with a dramatic spike and a sudden plunge, I recommend Mark Bostridge’s Florence Nightingale: The Woman and her Legend. For her first 34 years Nightingale was in self-isolation at home (the typical state for unmarried middle-class women), her desperation for adventure, as she put it, ‘eating out my vital strength’. For two brief years (1854-6) she cared for the wounded in the Crimea, after which she was sick herself. And for the next 50 years, propped up on pillows, she indulged her love of pie-charts. Preferring by far the administrative side of nursing, Nightingale was never happier than when demonstrating mortality rates in the colourful statistical diagrams she called ‘coxcombs’.

A less laudatory account of Nightingale’s achievement can be found in Lytton Strachey’s ironically titled Eminent Victorians, which I recommend to anyone experiencing generational differences. Written during the Great War and published in 1918, the aim of Strachey’s four brief portraits of Victorian icons (Nightingale, General Gordon, Cardinal Manning, and Dr Thomas Arnold) was to mock the self-regard of his predecessors and the ‘tedious panegyric’ of their biographical tradition.

Florence Nightingale was never happier than when demonstrating mortality rates on colourful graphs

By treating his subjects as flawed human beings Strachey blew the gaff on Victorian hagiography. Gordon (aka Chinese Gordon and Gordon of Khartoum), for example, is described as ‘particularly fond of boys’ and ‘a little off his head’. Bertrand Russell, reading Eminent Victorians in his conscientiously objecting cell at HM Prison Brixton, laughed so much that the warden had to remind him that prison was a place of punishment. Which proves that Strachey is an excellent companion for a period of lockdown.

Another conflict is fought in the pages of Edmund Gosse’s memoir of his childhood, Father and Son (1907). A member of the Plymouth Brethren, Gosse’s father, Philip Henry, was an evangelical Christian and marine biologist who explained the existence of fossils on the beach by arguing that God put them there to test our faith. The father’s beliefs are the prison from which the son must escape, and Gosse’s opening lines are the finest I know: ‘This book is the record of a struggle between two temperaments, two consciences, and almost two epochs. It ended, as was inevitable, in disruption.’ The book is the story, in other words, of every father and son, every mother and daughter.

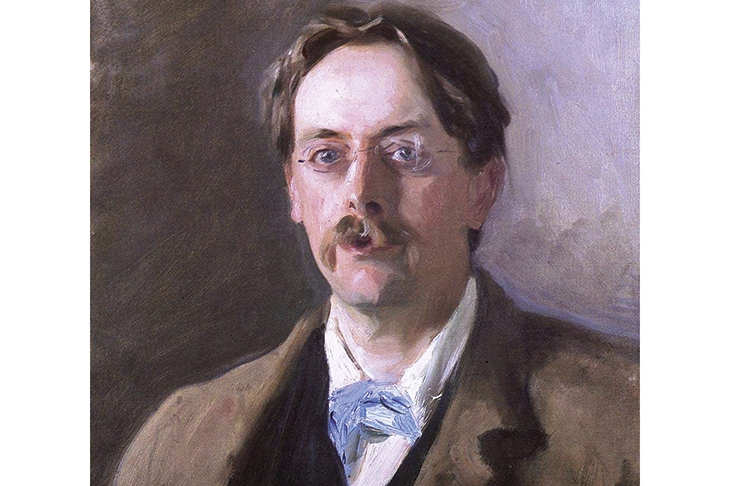

While good biographers, such as Strachey and Gosse, are always excellent company, the most enjoyable memoirs and biographies are those that play with its conventions. There is no better example of a convivial author and a rebellious book than A.J.A. Symons’s masterpiece, The Quest for Corvo. Symons was an epicure who collected musical boxes and co-founded the Wine and Food Society, and The Quest for Corvo, written in 1925, is a detective story describing his attempt to write the biography of the eccentric author Frederick Rolph, who went by the name of Baron Corvo.

While Strachey refused to revere his subjects, Symons refused to keep a respectful distance from his (there has always been a two-metre rule where biographers are concerned). The closer Symons comes to Corvo’s strange personality, the more the two men blend into one. By the end of the book it is impossible to distinguish the hunter from his quarry; Symons’s ‘quest’, we realise, has been for himself.

What The Quest for Corvo makes plain is that the best biographies depend on an identification of sorts between author and subject. The reason why Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson

(1791) is such an electrifying read is not because Boswell knew Johnson personally and could quote him verbatim, or because Johnson was ‘incapable of an ignoble or unworthy action’, but because the insecure and priapic Boswell projected an idealised image of himself onto the portrait he drew of his bearlike, fragile friend. The current pandemic offers the perfect opportunity for tackling Boswell’s Life of Johnson; but those who shy away from fat volumes (the Penguin edition has 1,327 pages) should read instead Adam Sisman’s Boswell’s Presumptuous Task. How, Sisman asks in his superb account of Boswell’s 17 years of writing and research, could such an idiot have produced the most celebrated biography in the English language?

Dr Johnson also wrote a biography of a famous friend, which also became a landmark in the genre. His Account of the Life of Mr Richard Savage, published anonymously in 1744 and still available, is a defence of the notorious poet and murderer who claimed to be the illegitimate son of Earl Rivers and duly terrorised Lady Macclesfield, the woman he insisted was his mother.

Johnson turned the dangerous, dissipated Savage into the prototype of the Romantic outcast, a man more sinned against than sinning. In Dr Johnson and Mr Savage, his spellbinding exploration of the mysterious friendship between the two men, Richard Holmes expands even further the boundaries of biography, turning it into something dreamlike and spectral. The friendship between the young Dr Johnson and the middle-aged Mr Savage was formed, Johnson wrote, when they wandered the London streets at night sharing the stories of their lives; but there is no record of them ever being seen together. They were in this sense, as Holmes’s title suggests, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The biographer and his subject are two versions of the same person. Now there’s an idea to increase your heart rate.

Comments