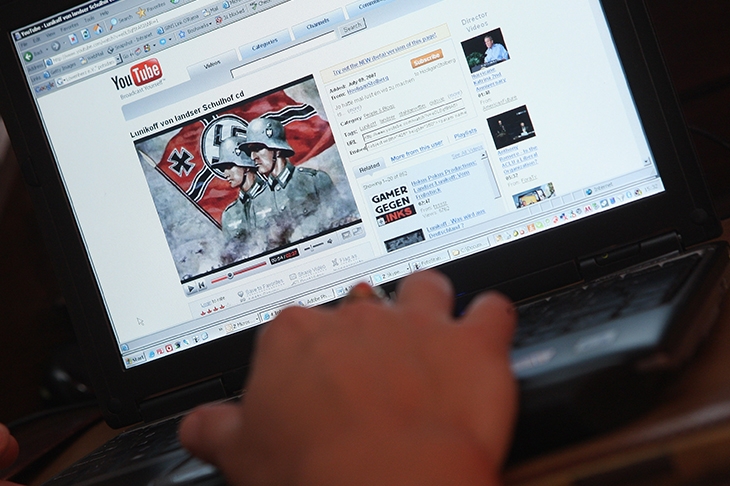

Shortly before agreeing, early last year, to pay token back taxes on a decade’s worth of UK-generated profits, Google also abolished its global slogan ‘Don’t be evil’. Instead it adopted a code of conduct that urged employees to ‘do the right thing’ — but at least in one important respect, they didn’t. Marks & Spencer, HSBC, Audi and numerous other top brands found their banner adverts displayed alongside a variety of YouTube hate videos which Google had failed to exclude, apparently because it did not have sufficient resources to monitor all the video content that was being uploaded at the rate of 400 hours per minute.

For fear of losing a chunk of its UK ad revenues, the company has apologised and promised to do better. But the episode reminds us again of the slipperiness of the 21st-century digital mega-corporation.

In Google’s case, that has meant paying taxes akin to those paid by terrestrial companies only as a negotiated last resort when embarrassed into doing so, while trying to duck responsibility for publishing much of the vilest and most disturbing material on the planet. Yet we all use Google many times a day, believing it to be a miraculous knowledge channel that is also benign, or at least morally neutral. And so it should be, but given its hugely influential position in all our lives, it needs to try a lot harder.

Here’s a Brexit opportunity

As I’ve said before, the bellwether of post-Brexit prosperity will be the health of the UK car industry, rather than that of the far larger financial sector. The City is nimble enough to look after itself come what may; it requires little more than plug sockets and clever lawyers to outmanoeuvre barriers to its trade. Car-makers, by contrast, require massive investment in research, robotics and logistics to keep them at the cutting edge of a globalised manufacturing system operating on the tightest of margins.

So every indicator is worth tracking. Peugeot-Vauxhall was a mixed signal, and a cloud hangs over the Ford engine plant at Bridgend. But there’s positive news from Toyota in Derbyshire, which is investing £240 million in an assembly line upgrade to match Toyota systems worldwide. Toyota’s European chief, Johan van Zyl, says he’s hoping for the same ‘safeguards’ against EU tariffs that Theresa May is believed to have promised Nissan; he also talked of sourcing more components within the UK.

If the first of those two provisos remains uncertain, the second is an opportunity. On average, only 41 per cent of parts in British-made cars originate here. Whatever the Brexit deal, it’s highly unlikely to offer carry-on-as-you-are exemptions for this industry alone. So the challenge in the automotive game will be to generate competitive new lines of supply, whether domestically or from faraway places we can trade with tariff-free. Let’s open a factory.

Bob’s comeback carriage

Lock up your Libor-linked instruments: Bob Diamond is back in the City. Five years after his scandal-driven exit as chief executive of Barclays, my old sparring partner — as I like to think of him — has teamed up with Qatari investors to buy Panmure Gordon, a stockbroking survivor from the 19th Century, for £15.5 million. That sum, as the FT sniffily pointed out, is rather less than Bob used to earn per annum in palmier days, and observers may be wondering whether he’s following a coherent strategy. Lately he has been trying without obvious success to build a bank in Africa and, through his private equity firm Atlas Merchant Capital, buying up a ragbag of financial ventures, including a Greek consumer credit business and now the almost-forgotten small-cap broking boutique of Panmure Gordon.

But at least his latest purchase has a history that match Bob’s own buccaneering spirit. The founder, Harry Panmure Gordon (1837–1902), was a high-living Harrovian who commanded the Shanghai Mounted Volunteers against the Taiping rebellion before returning to found his London stockbroking firm in 1876. ‘An extremely successful practitioner’, according to historian David Kynaston, he was also ‘one of the most talked-about men in the City’, not least for his collections of carriages, neckties and trousers — a pair for every day of the year. ‘Always full of push and energy… his restless temperament showed itself in staccato phrases’: that reminds me of Bob barking down the phone from New York: ‘I love the challenge, Martin, I love the business.’

In more recent times, Panmure provided a launch pad for the young Michael Richardson, a tireless dealmaker who was later labelled ‘Margaret Thatcher’s favourite banker’, and for the hyperactive international networker Ronnie Grierson. Old it may be, but Panmure Gordon looks an appropriate carriage for Bob’s comeback, if that’s what this is. He’ll surely never run a big British bank again, but as former business secretary Vince Cable remarked, ‘a boutique is less alarming.’

Hard-nosed capitalists

Melrose Industries is a lesser-known FTSE 100 company whose executives are reportedly about to partake in a ‘£200 million share bonanza’ under an incentive scheme, having already had £126 million from a pay-out in 2012. Are shareholders furious? Not at all, apparently: ‘They only make money if we do,’ said one institutional investor. Based on the Hanson conglomerate model from the 1980s, Melrose specialises in turning around underperforming industrial businesses and selling them; it has returned £3 billion to investors since it was founded in 2003. Its top team of Christopher Miller, David Roper and Simon Peckham did similar things in a previous venture called Wassall, Miller having once worked for Hanson and Roper having once been a City colleague of mine, though his talent was underestimated. Theirs is a hard-nosed form of capitalism, but one that creates efficiency and value. Hats off to them.

Comments