If you could travel back in time, would you kill Hitler’s mother, seek out your old house and play ball with your former self, or locate your (eventual) wife during her unhappy adolescence and punch her violent boyfriends? These are the dilemmas facing Jack, the hero of Daniel Clowes’s latest graphic novel. The murderous attitude towards Hitler’s mother (rather than towards Hitler himself) fits right in with an underlying misogyny throughout. Indebted to Hollywood for most of its ideas and its deficiencies, Patience only squeaks by in the Bechdel test.

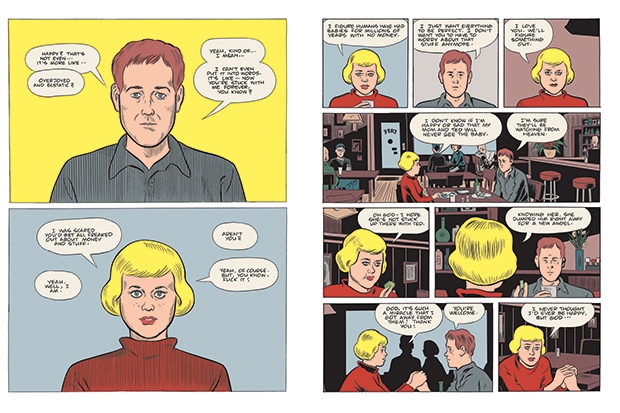

It begins wittily enough with the tip of a penis, a semi-circle of cervix, and a big white splodge in between. Across this romantic conception scene the year 2012 is emblazoned. Patience is ‘preggo’, as she despairingly puts it. She and her husband Jack want the baby but don’t have much money. He hasn’t even told her yet that his current job consists of handing out porno flyers. He’s about to fess up when Patience is murdered. As in The Fugitive, Jack is unjustly accused of the crime — but he gets off.

He proceeds to grieve for Patience and their unborn child for 17 chaste years, until 2029, when he happens upon a scientist with a time machine. Though Jack admits that ‘all that sci-fi bullshit is way too much to wrap my stupid-ass brain around’, now begins a bitter tale of love lost and reclaimed via time warps.

‘POOF…BOOM…POW!’ As with Woody Allen, the descent into magic makes your heart sink. Clowes doesn’t need to retreat from reality — he needs to get closer to it. Still, Jack’s psychedelic freakouts add visual variety, since Clowes’s usual flat, denuded pictorial take on things can make Patrick Caulfield’s formalised functionalism seem rich and generous.

The real subjects here are banal hopes and dreams, with a bit of mock heroism thrown in, all set within the customary graphic-novel gloomsville. Unquestioned stereotypes (fatsos, good-hearted tarts, even the wise black sidekick) and narrative clichés (the requisite murder, driving around, and male vengeance) reek of TV drama. There’s no actual law that says bleakness has to be portrayed in a bleak way. Edward Hopper rose above it.

Clowes gets more playful with the weirder psychological, physiological and ethical aspects of time travel. One two-page spread throws every known substance in the universe into flux, and Jack’s heart, intestines, muscles and veins briefly show through his clothing. Clowes is clever too at conveying night-time action. But the countless Vertigo-like depictions of Patience’s bland blonde head become aggravating.

Jack has his time-warp trials. He makes no friends when he attempts to pay for a 1985 breakfast with modern money (a veiled complaint, perhaps, that the Government ever changed the look of the good old dollar bill). A woman in a bar admires Jack’s 2029 jacket: ‘Whoa, did you make that yourself?’ In a casino he toys with the (Back to the Future) temptation to place bets on the results of ancient NFL games. How American, and how male, to remember those football scores in the midst of metaphysical, galactic disarray.

But Patience is most of all an invasion-of-privacy fantasy: a man goes back in time to snoop on his future wife, read her diary, and check her out at a young age — supposedly to prevent her later murder. The gory close-up of the dead Patience’s open eye is a bad sign, and this is where the really icky intrusiveness begins. It’s getting so a girl can’t be clunked on the head in peace any more.

Comments