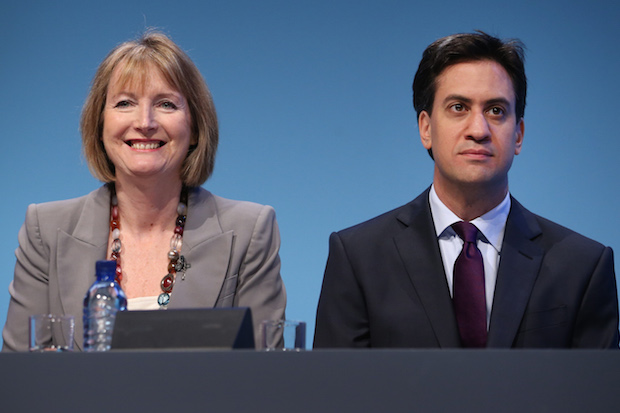

The fear and loathing within Labour continues with the admission from Harriet Harman that its voters were relieved it didn’t win the election. The party’s interim leader is interviewed in the Independent this morning, claiming that voters were ‘not massively enthusiastic’ about voting Conservative but ‘settled for the devil they knew’:

‘Sometimes after an election, you get a sense that people think ‘Oh my God, that is terrible, what a disaster.’ A lot of people felt that because we got nearly 40,000 new party members who were very disappointed. But there is an even greater number of people, even though they were not enthusiastic about David Cameron or the Tories, who feel relieved that we are not in government. We have got to address it. It was not a blip.’

Harman has come to this conclusion as a result of focus groups undertaken by Gordon Brown’s pollster Deborah Mattinson. These highlighted the feeling across the country that Labour was simply not ready for power. Ed Miliband has attempted to characterise his electoral failure as a result of ‘shy Labour’ voters who didn’t bother turn out. Harman’s analysis alternatively suggests that Labour’s failure was down to Miliband and Miliband’s operation — particularly on the economy. ‘If people had trusted us on the economy, they would not have worried that we would be pushed around by the SNP’, she says.

Harman is not the only one kicking Miliband when he is down. In the Guardian, the shadow education secretary Tristram Hunt attacks Miliband for being ‘uninterested’ in education policy:

‘As leader of the Labour party, Ed Miliband was deeply committed to apprenticeships, vocational education and childcare support. Yet sadly, he allowed himself to be perceived as uninterested in schools policy. And in our increasingly presidential politics, the media refracts every issue through the party leader’s personal capital. This, coupled with sincere concerns about “initiative-itus” and teacher exhaustion, tempered our radicalism, allowing the Tories to seize far too much of the education mantle’

Hunt also blames a lack of trust on Labour’s ‘muddled’ tuition fees policy. ‘There are strong economic arguments for investing in higher education and the current policy is loading massive debt upon the taxpayer’, he writes.

Given the scale of Labour’s defeat, it’s unsurprising that Harman and Hunt are keen to distance themselves from Miliband. But once the leadership contest is properly underway next week, the party will need to look at solutions. It’s obviously important to discuss where the party went wrong, but Labour won’t have this freedom for long.

The prescriptions from Harman (stronger on the economy) and Hunt (consistent on education) may not seem particularly unique, but they are both themes that the next Labour leader must consider when figuring out how to take the party forward.

Comments