It was Nervtag that did it for me. The New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) was responsible for reviewing, and then delivering, the bad tidings to the government about a new variant of the Covid-19 in the UK. So much more easily transmitted did the group judge it to be that, within hours, a Prime Minister who had said he wanted to protect Christmas at almost any cost had cancelled it, and France led what became a procession of more than 40 countries curbing travel with the UK.

As alarming as the news was in itself, the name coined for the group of scientists bringing it to us was, if anything, more so – to the point where you wanted to ask whether the acronym might have been dreamt up first, in order to spread maximum fear, before the individual words were then made to fit. What, after all, does Nervtag conjure up? A serious brand of nerve agent, obviously, that makes novichok sound small and tame by comparison? Or the shadowy brotherhood of those who plant it? Or maybe a dark creature, with fangs, that lurks just to the side of your sightline.

Among all the terms that have tracked the course of the pandemic, Nervtag smacks more of spookery than medical science. But it is not alone. We have grown used to SAGE, which by now sounds almost venerable, with an added dash of ancient mystique. But the Scientific Advisory Group on Epidemiology – whose members, remember, were unidentified at the start – relies on information given to it not just by the apparently down-to-earth COG-UK (COVID-19 Genomics UK) and the functional-sounding HDR UK (Health Data Research UK), but from two groups straight out of an intelligence manual.

As the pandemic has progressed, it has only strengthened its grip on our vocabulary

What, after all, are we to make of SPI-B and SPI-M – respectively the Independent Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours and the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M) – names that slip off an interviewer’s tongue before the listener has had time to digest it? SPI-B could indeed be as suspect as it sounds, given that its purpose is to gauge how the Great British public will respond to being told to wash their hands and ‘stay at home’, or, indeed, to being ‘locked down’.

Increasingly, it seems, a whole pandemic lexicon has evolved that – consciously or not – generates an air of coded menace that is more readily associated with the aspiring James Bonds at Vauxhall Cross than with the kindly souls endeavouring to save lives just a little further down the Thames at St Thomas’s.

Once upon a time, you would listen to the news and realise things were getting serious when COBR(A) was called into session – an acronym a million times more threatening than the bland Cabinet Office Briefing Room A that it stands for. I often wonder who the genius was who glimpsed the letters on the Civil Service schedule for the day and instantly grasped the scary national use to which the initialised serpent could be put.

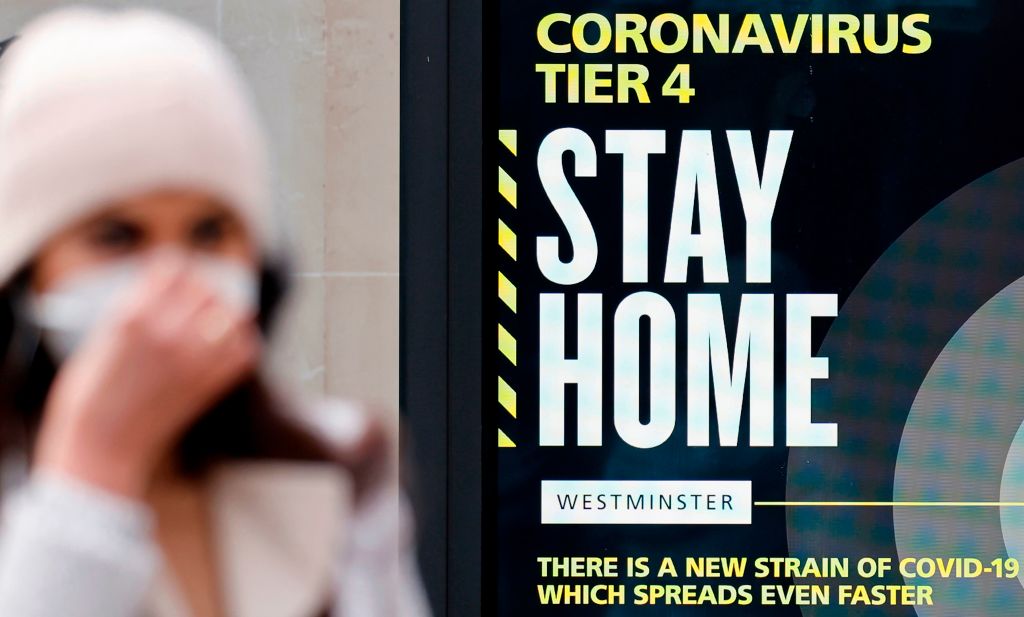

As the pandemic has progressed, it has only strengthened its grip on our vocabulary. COBR(A) now denotes one threat among many. The day when we stopped saying Coronavirus, or even ‘novel Coronavirus’ – a term more redolent of curiosity than fear – and switched to the more clinical-sounding Covid-19, or just Covid, crossed a threshold of sorts. When did masks become ‘face-coverings’, and why?

Some of the most pedestrian intruders – perhaps from a dated Civil Service handbook – seem to be slipping out of common usage as quickly as they slipped in, thank goodness. We don’t hear that much about ‘ramping up’ anymore, still less about doing it ‘at pace’ or ‘at scale’ – which could mean that whatever was supposed to be done had been accomplished, or – perhaps more likely – that it hadn’t been.

So familiar have semi-clinical terms, such as isolate, self-isolate, social-distance, become that we hardly notice them any more. We hear expressions such as permitted exercise, key workers, essential shops (and their opposite) every day – yet they would have been incomprehensible in their current meanings even a year ago. To panic-buy is now a verb in its own right, as is, alas, an early staple of Downing Street press briefings, to sadly-die.

And who would have thought a time would come when the unique selling point of the London Tube would not be its frequency or its speed, or its all-night service at weekends, but its hygiene? It is using, TfL adverts boast, not just disinfectant, but ‘hospital-grade disinfectant’ – and it has teams out spraying and checking that the handles and rails are up to scratch. Who could have forecast either that Dettol, that most boring leitmotif of a British childhood, would have some of the most imaginative adverts around.

There is a special commercial tone, too, full of soft words and faux-compassion. Instead of promoting special offers or credit terms, the soundtrack to your rare foray into a non-essential shop will be to stay well, stay safe, social-distance, use sanitiser – and it is the same, as I can vouch from my brief summer travels, across much of Europe. Barely a decade after almost collapsing the economies of the Western world, the big banks have adapted to the pandemic, too. In commercials that sound more like the old after-lunch ‘Listen with Mother’, they promise to listen, whenever and wherever you ‘feel comfortable’ (the Halifax); Lloyds offers softly condescending encouragement to ‘shop local’.

Nine months in, the first question has to be how long the pandemic has to run. But another might be whether its very particular lexicon survives its passing. Has it imprinted itself indelibly in language, or will we banish the words along with the memories as soon as we can? Personally, I will be overjoyed to see the back of self-isolation and social-distancing, but there is something about Nervtag and SPI-B, at least, that qualifies those names to live on as cyphers for the age.

Comments