The reported decision to postpone the implementation of the Assisted Dying Bill until 2029 might, one must pray, turn out to be a form of legislative euthanasia. MPs, looking at the process, began to resemble a patient who, having first of all declared his wish to end it all, then begins to worry that it will not be as simple or painless as he had been led to expect. It is one thing to express a fervent wish to release people from unbearable suffering and quite another to frame safe procedures which involve the state, the judiciary and the medical profession in helping people kill themselves. It was a bad mistake, too, for Labour, under Keir Starmer’s leadership, to indicate that although MPs would have a free vote, assisted suicide was a modern, cool, Labour idea. (The party long ago made a similar mistake about abortion.) Conscience issues should be just that. If they are distorted for party reasons, troubled consciences are the result. When I debated these matters with Lord Falconer in this paper early in the proceedings, he was at pains to emphasise the elaborate safeguards, notably the putting of each decision before a family court judge. As the debate has continued, it has become clear that judges are not mad keen to administer a politically correct version of the death penalty and, as Wes Streeting was brave enough to hint, the medical profession is quite busy enough saving rather than taking lives. Delay does not make the bill, with far too many delegated powers, better. But it should embolden its opponents.

Many remember the photographs of Diana, Princess of Wales, walking through a field of landmines. She may have had an eye to its importance as a metaphor for own predicament, but she also had the serious purpose of drawing attention to the horror of such weapons and the way they linger. In 1997, the year of her death, the Ottawa Treaty banned the use of anti-personnel mines. From the start, the problem was that the baddies – Russia, China and North Korea – would not sign. In the past three years, Russia has planted tens of thousands of landmines on the bits of Ukraine it has occupied. Ukraine has had to retaliate in kind. Now Poland and the Baltic States are signalling their intention to withdraw from the treaty and the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Lithuania, indeed, decided to withdraw from the latter in July. Britain complained. But what else would any sensible democracy faced with the close and growing threat of Russia do? Such weapons are extremely effective deterrents against invasion (and were largely responsible for stalling the Ukrainian counteroffensive). The United States refused to sign at Ottawa because of the danger of North Korea keeping mines while South Korea gave them up. As a new research note from Policy Exchange argues, Britain should give the lead in supporting the European countries which are the most active supporters of Ukraine. No one has ever been able to counter the wisdom contained in Belloc’s famous rhyme: ‘Pale Ebenezer thought it wrong to fight,/ But roaring Bill (who killed him) thought it right.’

This justified desire of Nordic and Baltic states to be battle-ready shows how inane are the attacks made by J.D. Vance and Pete Hegseth in their insecure Signal chats in which Hegseth disclosed the plans and timing of a proposed American attack on the Houthis. Both men railed against the free-loading weakness of ‘Europe’. What do they mean by ‘Europe’? It tends to be the countries which were liberated by the end of the Cold War which remain most actively appreciative of that victory. Among the main ones, only Hungary sucks up to Putin. Poland leads the military way. The Baltic States are rearming as fast as they can. Sweden and Finland have abandoned their neutrality and joined Nato. All of them were, and would still like to be, pro-American. What is, to use Hegseth’s word, ‘PATHETIC’ about these countries? Why do Trump’s top-security chatterboxes despise the democracies their country helped bring into being?

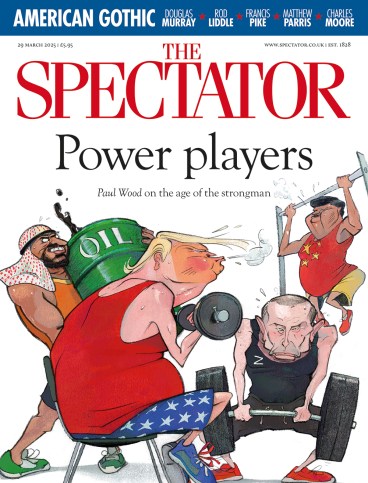

On p10, Paul Wood analyses the age of the strongman. By ‘age’, he means era, but their actual age is of interest – Xi Jinping and Erdogan are 71; Putin, 72; Trump, 78; Ayatollah Khamenei, 85. Why are the old so angry?

Forty years ago, The Spectator supported the privatisation of British Telecom, but we got annoyed when the company used it as an excuse to get rid of its ubiquitous red telephone boxes and replace them with flimsy, colourless public phones. We ran a campaign on the subject which won reprieves for a good many of the old boxes. What neither we, nor BT, envisaged was that the whole idea of a telephone box would be rendered obsolete within ten years by the mobile phone. By the mid-1990s, in cities at least, the only remaining use for telephone boxes was for ringing prostitutes who left their cards in them. Nowadays there are hardly any public phones left. Where the red boxes survive, however, they thrive. When I walk through Parliament Square, I have to fight my way through the crowds, including Chinese couples in their wedding outfits, queuing for selfies beside the boxes. If only our campaign had triumphed first time around, the land would be teeming with red phone boxes bringing tourist photo-opportunities to every village. I am sure modern technology could have come up with modest fees to keep in good repair the best pieces of street furniture ever devised.

I would not dream of taking sides in the dispute between Rupert Lowe and Nigel Farage, but I find it profoundly depressing that it is to be fought in the law courts. Surely politics by litigation is part of the decadence which Reform wants to cast off. As the late Alan Watkins never tired of reminding readers: ‘Politics is a rough old trade.’ Surely its disputes should be settled ‘man-to-man’, as they used to say in the East End.

Comments