My first love was a penguin. Pengwee was an adorable brown and white emperor chick who had my heart and broke it the day he dived into the bath. After a week in the airing cupboard he smelled of fish – surprising in a soft toy. But then penguins are surprising.

Towards the end of the Cretaceous period, 65 million years ago in Zealandia, a fragment of the Gondwana supercontinent, penguins waddled off along their own evolutionary path. Other birds flew through air; penguins flew through water.

Natural selection pi-pi-pimped up the penguin (sorry) to astonishing specialisation. Hunting in black oceanic deeps, many species can see in ultraviolet. Kings and emperors can magnify the pupils of their eyes up to 300 times so as to gather all available light and then shrink them to needle points to avoid snow blindness on the sea ice.

A huddle of emperors in the -60°C Antarctic winter night can generate +35° of heat in their centre, and the birds rotate within their scrums to avoid being cooked as much as frozen. All penguin species beguile us with their upright stance and comical air, triggering that affection for small things, children and duffers which seems hardwired in us. But at sea they are little Poseidons. My first sighting in the wild was a Galapagos penguin, which zipped about below a dock on Isabela island. I could not believe how quick and sinuous it was, how slick its changes of direction, how ferociously it could accelerate and how swiftly jink. The fish had no chance. Now, thanks to Peter Fretwell’s The Penguin Book of Penguins – the model of a popular monograph, and beguilingly illustrated by Lisa Fretwell – I know how they do it, and pretty well everything else about them, too.

The author is a lead scientist with the British Antarctic Survey and a world expert on emperor penguins. He writes with concision and a lightness of touch which make absorbing complicated facts about penguins a joy. And there is much to know. Penguin speed, for example, comes from scaly flipper feathers which create sheathes of bubbles, reducing drag and generating lift. The Russian Shkval torpedo works the same way: encased in a bubble of air and gas it can reach 230mph. The Gentoo penguin does 22mph, which is still mighty fast at sea, and the Adélie penguin goes one better. Fretwell explains how it can squeeze air out of its feathers, creating jet propulsion: ‘Like a nitro-boost… extremely useful if you need to escape from a hungry orca or leopard seal, or even to jump up on to the sea ice.’ Jet-propelled Adélies can fire themselves out of the water and three metres into the air.

One penguin runs up to Lafferty and apparently declares its undying love

Wouldn’t you love to see that for yourself? If you think so, you should read An Inconvenience of Penguins first, which may lead you to think again. The author, James Lafferty, sets the tone on page one: ‘This is not an academic text, and certainly not a guide book. In fact, I would advise against attempting to see every penguin species in the world.’

Lafferty’s story is refreshingly free of travel-writing clichés. He is not trying to find himself or heal from something. Proposal, marriage and divorce are mentioned, but there is no trauma to overcome or epiphany sought. The nearest we get to a reason for his decision to visit all 18 of the world’s penguin species is his love of Antarctica and his desire to be there as much as possible.

We travel to South Georgia, to Tristan de Cunha, to the outer rims and blasted rocks of the remotest parts of New Zealand and Antarctica, and eventually look representatives of each species in their remarkable eyes. Throughout these pages, penguins waddle, squeal, copulate (with the same and opposite sex), constantly fight each other, do battle with giant petrels and skuas, are ripped apart by seals and orcas, lay and incubate eggs, adopt and defend each other’s offspring and defecate copiously over each other. One runs up to Lafferty and apparently declares undying love for him.

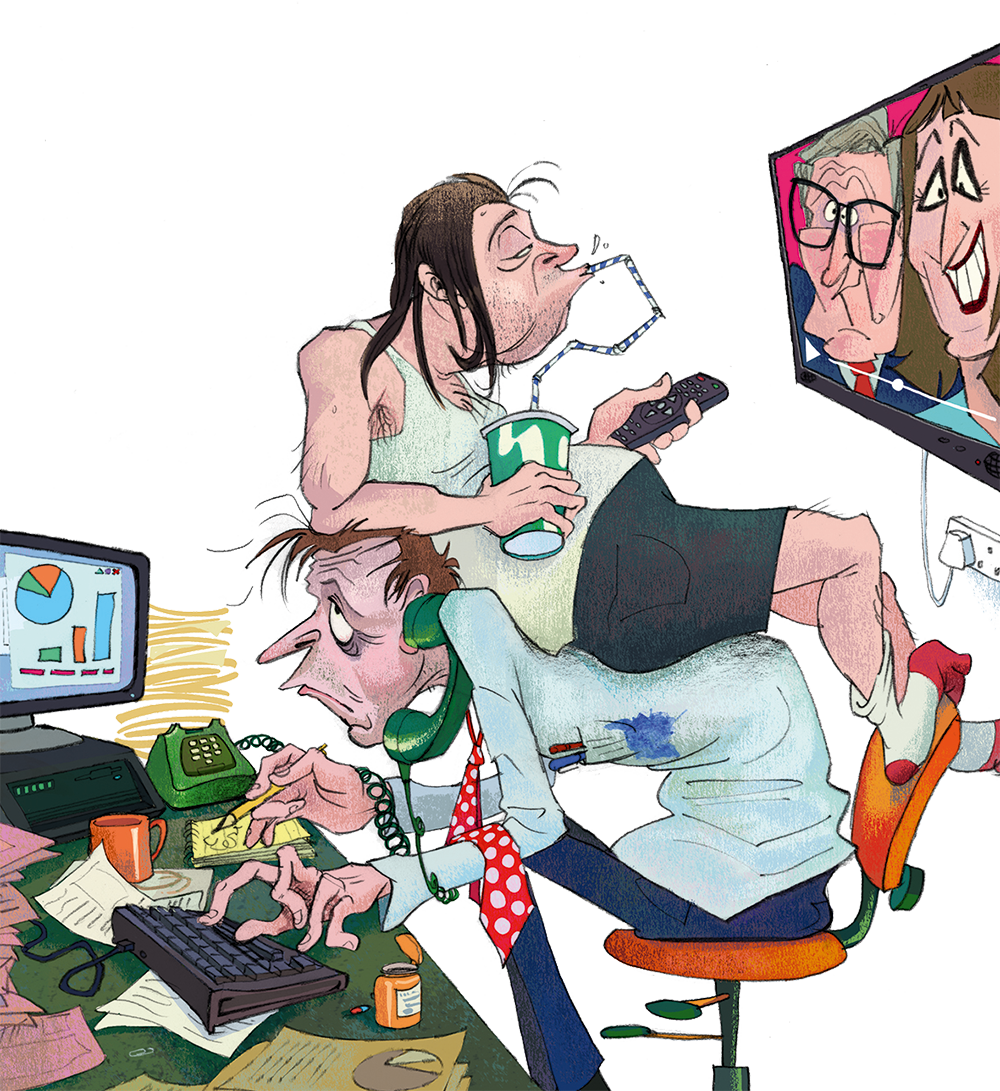

The result is a terrific read. But even penguins are not quite as interesting as people – a species to which Lafferty makes a delightful guide, prone as he is to directness, misanthropy and the sort of jaded have-you-ever-seen-a-hotel-as-crap-as-this sensibility one more usually finds in travel photographers. In order to accomplish his goal, he uses every trick in the book – pitching, wheedling, ‘basically writing ads’ for travel companies – and becomes a guide.

His best and real subject, sown slyly through the pages, is his fellow passengers. The writing lifts less when describing the circumnavigation of Antarctica than when he eviscerates some of the people who pay £40,000 to do so. One of them phones the ship’s bridge to inform the officers that according to his iPhone they are heading north, not south. We have all suffered ‘the person making a long and sincere thank you that wasn’t needed but gets a baffling amount of applause anyway’, whom Lafferty footnotes (he loves a footnote) with: ‘Let’s face it, an American.’ Similarly, ‘the snide asider, who thinks they’re being lied to by the trained professionals keeping them alive’.

As an account of the tourist industry, its clients and the travellers’ world which Lafferty and the rest of our profession censor or burnish, this book may be unbeatable. The sequence in which Lafferty takes strong LSD in a penguin colony on the Falklands is easily the best, and begs to be the climax. He thinks it hasn’t had any effect, stands up, and suddenly all the penguins are six inches high. He is convinced he is ‘going to drop through a crevasse into a penguin netherworld, dug out and ruled by burrowing Magellanics’. Yet another hard-earned penguin encounter actually closes the book; but it is being guided by Lafferty into Pengwee’s acid kingdom that really stays with you.

Comments