An infuriating benefit of readers’ online comments beneath the efforts of a columnist like me is that as you read the responses an understanding dawns of the column you ought to have written.

Some readers are stupid, unpleasant or obsessive; but most are not. As you learn their reactions you see where your argument was not clear, where you were short of information, and where you were simply wrong. But more than that, you sometimes tumble for the first time to where the nub of a problem that perhaps you danced around may lie.

Last Saturday I wrote for the Times about the self-righteousness of spokesmen for public services threatened by government cuts; about veiled threats by the police to stop policing, and by barristers enraged by cuts to legal aid. I wrote, too, about the British Medical Association’s shroud-waving. My argument was that lots of people, employees in both the public and the private sector, provide services that are useful or even essential to the public, and that those who work in the public sector should claim no special moral right to be spared the consequences of austerity.

The column drew a big response — impassioned both for and against my case. As I read on over the weekend, the uncomfortable realisation dawned that the root of the problem was something Conservatives like me are rather supposed to approve of and are inclined to pray in aid of our case. It’s called ‘the public service ethos’.

The idea is variously expressed. We talk about the public service ‘ideal’; the special sense of duty that (we suggest) ought to actuate teachers, nurses, and all who work for the public good. We insinuate that theirs is a calling rather than just a job; that money shouldn’t loom large among their ambitions; that feelings of responsibility to those who depend on their work should be more highly developed among them than among those employed in profit-making organisations; indeed that ‘profit’ is almost a dirty word in their line of business. I’ve noticed in London Underground carriages an advertisement for Transport for London whose message is that TfL is not a profit-making outfit — the implication being that we ought therefore to admire its endeavours more. And this from a Conservative Mayor of London.

As with the organisation, so with those who serve it: drivers of not-for-profit Tube trains, nurses in NHS hospitals, teachers in state schools, barristers taking briefs from legal-aid defendants, are thought to inhabit a subtly but distinctly higher moral plane than their equivalents in (say) private hospitals, airlines or independent schools. They begin to believe it of themselves.

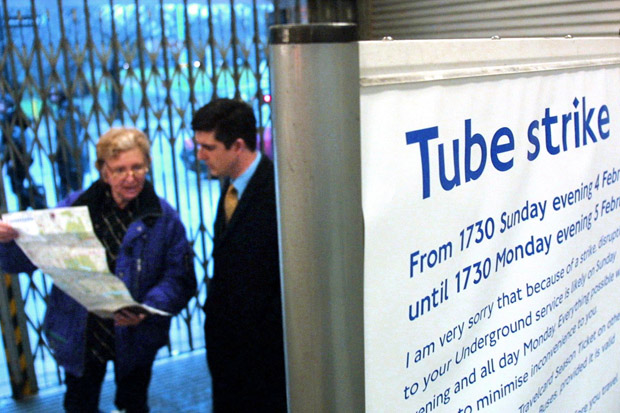

So when Conservative politicians inveigh against junior doctors who might, by striking, ‘put patients’ lives at risk’; or firemen or ambulance men whose industrial action might place ordinary citizens in jeopardy, or RMT members who by bringing the railways to a halt might inconvenience members of the travelling public, they are feeding the cultural meme that those who provide public services have special moral responsibilities to their customers. They are also (perhaps unwittingly) contributing to the idea that for public sector workers, virtue is, if not entirely its own reward, at least a reward that compensates for somewhat lower wages.

Were I a Marxist, I would argue that capitalist society has invented the idea of the public service ethos in order to get more out of workers for lower wages. Not being a Marxist, I confine myself to remarking that this paternalistic view of the state sector tends to substitute a sense of duty for the desire to enrich yourself; a substitution that’s highly convenient to the employer.

Time and again in the online comments for my column, contributors who work in the public sector have been assuring their readers that they embarked on their careers with the ideal of service, rather than money, foremost in their minds. And can you blame them? Isn’t this what our culture has been teaching them? Isn’t this the reward that we’ve suggested they should prefer to higher wages?

Perhaps, then, we should think again before tut-tutting when junior doctors, hospital workers and schoolteachers wag their fingers at Tory ministers and paint horrifying pictures of the suffering the public they serve will endure if this or that proposed cut goes ahead. Have we not fed that mentality by suggesting that they shouldn’t be in it for themselves, but for those who depend on them?

I wonder whether the ‘public service ethos’ does more harm than good. Used, variously, as an argument against trying to measure the value of public sector activity (‘these things can’t expressed in crude figures’), trying to impose efficiency reforms (‘bean-counters can’t understand the value of what we do’) and against virtually any cuts to any public service at all (‘we’re not doing this for profit but because we know people need us’), a central belief in many public servants’ minds is that they are working for the greater good and have no vested interests of their own, and are therefore above the selfish arguments of the rest of us. This poisons rational consideration of costs and benefits in the public sector.

Anyone who has worked in a charity will be familiar with the rancid element that can be introduced into any co-operative endeavour by the consciousness of every comrade that he or she doing this for love, not money. God spare those who want to get things done efficiently from the spirit of voluntarism. The public service ideal conveys a subtle hint of voluntarism, encouraging a sense of grievance that workers’ efforts are not properly appreciated or supported — a grievance writ large, for example, among the teachers’ unions.

Samuel Johnson remarked that no man was more innocently employed than when making money. Perhaps he overstated; but a weekend spent in the (virtual) company of public sector workers who feel the world misunderstands and undervalues them has left me close to recommending this mission statement for the public sector: ‘A job, not a vocation.’

Comments