Sam Leith is enthralled by the larger-than-life genius, August Strindberg — playwright, horticulturalist, painter, alchemist and father of modern literature

When I’m reading a book for review, it’s my habit to jot an exclamation mark in the margin alongside anything that strikes me as particularly unexpected, funny or alarming. I embarked on Strindberg: A Life with — I’m ashamed to confess — the expectation of a weary plod through 400-odd pages of lowering Scandinavian neurosis, auguring a low exclamation-mark count and a high number of triple zeds. But by the end, there was an exclamation mark beside almost every paragraph. If it hadn’t been for the occasional ‘hahaha’ and ‘bonkers’, you’d look at my copy of Sue Prideaux’s biography and think I’d been signalling in Morse code.

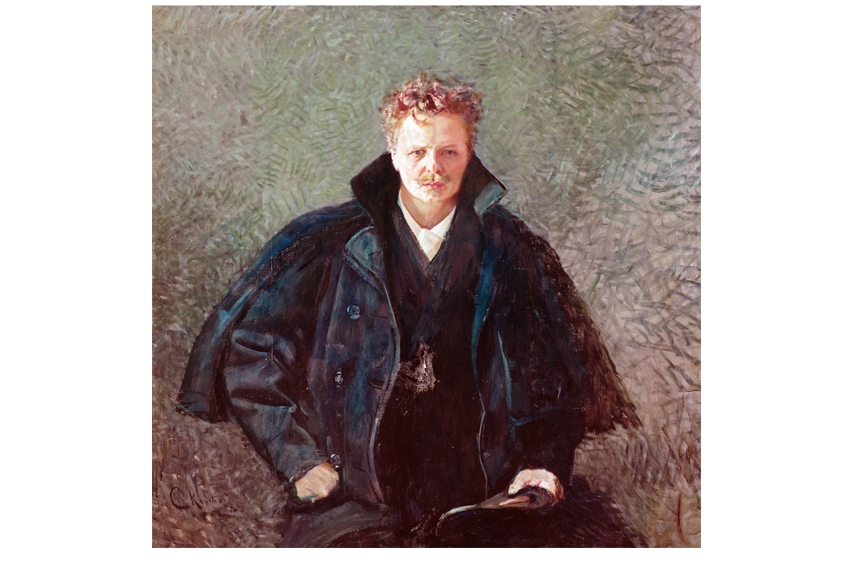

What an absolutely extraordinary man August Strindberg was, and what a tormented, demented life he led!I haven’t read such a fascinating biography for ages. The Strindberg we know — the author of Miss Julie, The Father and the phantasmagorical Dream Play — is just the tip of the Swede, so to speak.

Prideaux states in her opening sentence: ‘During the writing of this book it became apparent to me that outside Scandinavia Strindberg is best known for two things: Miss Julie and alarming misogyny.’ But as she points out, Strindberg was attacked by feminist contemporaries not because he wanted to keep women down, but because his ideas for female emancipation went far beyond what they found comfortable. And in addition to Miss Julie he wrote 60 plays, three books of poetry, 18 novels, nine autobiographies, 10,000 extant letters, tons of journalism … and the contents of a green flannel sack he hauled around after him, described thus by his second wife:

About one yard in length, with gentle billowing valleys and summits and fastened by a cord. It contained all his manuscripts. It contained his theory that plants have nerves. It contained his theory that elements can be split. It contained theories that refute Newton and God himself.

He was one of those figures like Aristotle, Leonardo or Newton who wouldn’t stick to one thing. He was after the answer to life, the universe and everything, and he put in the hours. He was a painter, a horticulturalist and an experimental photographer. As well as tense psychological dramas he wrote satire, comic fiction, fairy stories, a cycle of history plays, even — experimentalist that he was — a short story consisting entirely of telephone numbers. Prideaux contends that if only he hadn’t been writing in Swedish he’d be regarded as one of the founders of modern literature, and by the end — though this isn’t a critical biography — you’re more than ready to believe her. Here, at any rate, is a particularly jagged, colourful and important piece of the Symbolist-Expressionist-Modernist-Naturalist-Surrealist-Absurdist jigsaw.

He was a man of fierce energy — he produced a (fairly useless) 1,000-page history of Sweden in 18 months, and one three-year burst saw him write 17 plays. He was prone to consuming enthusiasms, which he referred to as ‘buttonology’: the pedantic attempt to classify a particular branch of knowledge. He wrote essays on the history of Aquavit and on Sino-Swedish relations (he taught himself Chinese and Japanese). He discovered a long-lost map of Central Asia that won him a silver medal from the Imperial Geographical Society of St Petersburg. He charted the different dialect names for ladybirds throughout Sweden, and made a particular study of the water closets in French hotels.

In addition to freeing drama from artifice and convention, and social relations from the prison of received ideas, Strindberg spent a lot of time trying to turn lead into gold. It’s one of the strange and counter-intuitive things about the progress of Enlightenment ideas that scientism went hand in hand with mumbo-jumbo. The existence of invisible forces such as electricity and magnetism gave succour, rather than otherwise, to occultism. Ideas about evolution could be folded into the old story of alchemy: matter was in a constant state of transformation.

That said: not for old Strindberg, it wasn’t. In addition to various lead/gold unsuccesses, he became convinced the elements could be broken down, and stunk the place out trying to extract carbon from sulphur.

Eventually he did . . . but as the traces of carbon he found in the sulphur might well have come from the ash of the cigars he smoked during his labours, the successful experiment could not reliably be replicated. Nevertheless, Strindberg maintained a steadfast belief that he had succeeded.

No wonder he felt a bit peaky as time went on. On a daily basis, by his own reckoning, he came into contact with arsenic, chlorine, cyanide, mercury, nicotine, sulphur, vitriol, absinthe and the sleeping drug sulphanol. In later life he went stark mad — a condition from which he was (partially) restored by the realisation that the garden path in the house where he was living closely resembled Swedenborg’s description of the geography of Hell.

We know things about Strindberg — thanks, in part, to his keeping of an ‘Occult Diary’ — that we know about few other writers. We know he feared thunder and the dark, liked cleanliness and thought that sharing a double bed was a filthy habit. We know how big his penis was (he measured it, in the course of settling a bitter argument with his wife): 16cm by 4cm. We know that when he was in the grip of an erotic obsession everything smelled to him of celery. We know he had a definite thing for boots.

Born in 1849, he had a horrible childhood, and was bullied by both his parents. He rejected his father’s snobbery and his mother’s pietism. He was, for the most part, kind. Even when he was flat broke, he bought handfuls of cherries twice a day to feed a bear in the zoo that he had become fond of. The bear was called Martin. When Strinberg behaved badly — as he did towards his first wife, Siri and their children — guilt weighed on him. Having once been falsely accused of stealing a peacock, 18 years later he startled a bookseller by exclaiming at random: ‘I have never stolen a live peacock!’

Nothing was ever simple for him. He fell in with crooks, swindlers and Satanists. When he was accused of impregnating an underage girl, he denounced his blackmailer to a policeman — who himself turned out to be being blackmailed by the same man. Strindberg was repeatedly sued for blasphemy. It’s a mark of his radicalism that it was 1984 before an unexpurgated version of Miss Julie played in Sweden.

He lived, gregariously, in Stockholm, Paris and Berlin — everywhere he went cultivating a more or less drunken salon of some sort. His love life was a non-stop disaster, and his finances were always precarious — a clue to the reason for which can be discerned in a triumphant letter he wrote to his wife: ‘I’ve succeeded in borrowing some money, so we are debt-free!’

All this — and, lawks, so much more — is related with enormous panache and affection. Prideaux has a lovely dry turn of phrase: ‘Strindberg’s differences with Grandfather Reischl over their attitudes to money, Jews and pianos finally volatilised’; ‘the Karlsborg Fortress [was] a construction the size of a Soviet hotel’; Strindberg’s first wife had ‘a graceful neck, a feature much prized in those days when people were still beheaded in Sweden’. In other words, you can see in the prose how much fun the author is having with Strindberg. Anyone reading her marvellous book will have that much fun too.

Comments