Just as it will sometimes happen that a critic feels obliged to preface a review with a declaration of interest, so I should now declare a lack of interest. Prior to being commissioned to review David Bellos’s heroically well-researched and hugely entertaining biography, I confess I had never managed to finish one of Romain Gary’s books.

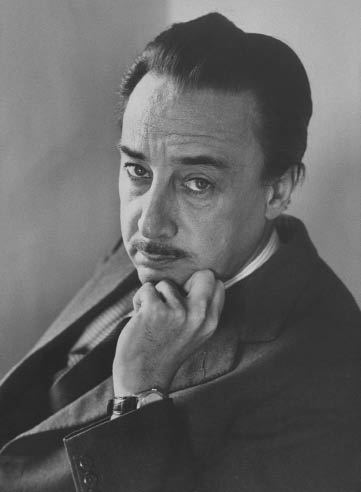

When I lived in Paris in the 1970s Gary was in fact my near neighbour. A conspicuous figure around Saint-Germain-des-Prés, ‘disguised as himself’, as Bellos phrases it, flashily tanned, resembling in his flamboyant black-leather outfits a cross between a plumper Dali and the clownish caricature of a Mexican dictator, the thick dye of his improbable jet-black hair and moustache visible from the far side of the boulevard, a committed Gaullist to boot, which didn’t help in the post-1968 years, he had about his person an aura of glossy sleaze, if you’ll pardon the oxymoron.

And his novels? Yes, they were regular bestsellers, had been (mostly atrociously) filmed — The Roots of Heaven by John Huston, Lady L by Peter Ustinov — and twice won the Goncourt (the second time illegitimately, of which more later). But one didn’t read them. One would not have been seen dead reading them. Nobody read them. Except, of course, the public.

Such an admission may make me seem snobbish and elitist, but even Bellos, confronting his subject’s lamentably prolific output, has frequent recourse to qualifiers like ‘kitschy’ and ‘middlebrow’. So much so that one initially cannot help wondering what could have attracted him in the first place: he is, after all, best known as the translator of Georges Perec, a writer with whom Gary had, save his Jewishness, absolutely nothing in common.

Or had he? Wittgenstein wrote somewhere that, on the profoundest level, differences resemble each other more than similarities do, and it becomes increasingly obvious that what fascinated Bellos was the degree to which both writers sacrificed themselves to the cult of literary games-playing. On everything he wrote the Oulipian Perec imposed the grid of a rigorously adhered-to linguistic constraint (notably, the lipogrammatic e-less-ese of La Disparition), while the Olympian Gary carried matters just as far in the reverse direction, systematically emancipating himself from most of the conventional codes and pieties to which the writer as public figure is expected to pay at least lip-service.

He was, supremely, a congenital liar. He was, indeed, such a compulsive, chaotic liar one couldn’t even believe the reverse of what he said. Although he led an exceptionally mouvementé life — he was born in Russia in 1914, emigrated with his domineering mother to Nice, fled to Britain in 1940 to join the RAF’s Free French squadron, in which he served with real distinction, was appointed French Consul General in Los Angeles, married Lesley Blanch and Jean Seberg, but was also rumoured to have a taste for underage prostitutes — he still couldn’t resist lying about it. A tiny, trivial but typical example will suffice. The fact that in 1945 he received the Médaille de la Libération from one General Vallin wasn’t good enough for Gary; in Promise at Dawn, a novel masquerading as a memoir, it’s pinned on his breast by De Gaulle himself. Bellos records scores of these often futile fibs.

And it was a monstrous fib which brought about his comeuppance and may have contributed to his suicide, only a year after Seberg’s decomposing corpse was discovered in an abandoned car. Perhaps not surprisingly weary of what Bellos calls his ‘oppressive celebrity’, Gary invented another writer, ‘Emil Ajar’, wrote three very lucrative novels under that pseudonym (it appears he just couldn’t help making pots of money) and even inveigled his cousin into assuming Ajar’s public persona. For some inexplicable reason, though, he allowed the hoax to outstay its welcome. When Life Before Us, the second novel published under Ajar’s byline, was awarded what was, in reality, Gary’s second Goncourt (forbidden under the Prize’s rules), he found himself ensnared by his own foxiness.

In so painstakingly unpicking his subject’s economies with the factual truth — to expose one of Gary’s lies he consulted the Warsaw telephone directory for 1926 — Bellos persuades us that he was a significantly more complex and even tragic figure than could ever be inferred from the internal evidence of any individual work. Which is ultimately the problem with his hypothesis: unless you read his biography first, you are still likely to find Gary’s books as coarse and second-rate as I did. That’s Gary’s problem, however, not Bellos’s.

Comments