Damian Thompson highlights the gems among the prolific and pilloried composer’s nine million notes

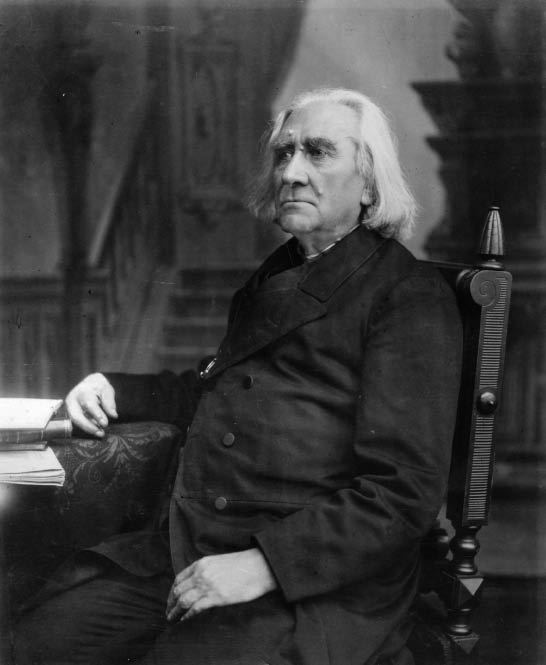

The extraordinary thing about Franz Liszt is that he remains one of the most famous composers of the 19th century despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of his music is forgotten — and likely to stay forgotten.

He wrote enough of it, that’s for sure. If you were to listen to his works one after another without interruption, it would take about a week. I’m basing that estimate on the fact that Leslie Howard’s 98 CDs of Liszt’s complete piano music, which are just about to be reissued by Hyperion, last for just over five days. That’s nine million notes spread over 12 miles of printed pages, in case you were wondering. Add the orchestral and sacred music and you’d have about 120 CDs.

But, even though 2011 is Liszt’s bicentenary year, there was never any danger of Radio 3 giving us ‘Liszt Week’. Even his fervent champions — who are always telling us that he beat Wagner to the Tristan chord, reinvented symphonic form, anticipated Schoenberg in his frighteningly spare last piano style, etc. — might blanch at the prospect of wall-to-wall Liszt. (Radio 3 announcer: ‘And that was the Marche pour le Sultan Abdul Medjid-Khan. Next, the Tarantella d’après la Tarantelle de “la Muette de Portici” d’Auber.’)

How much of Liszt’s music shows him at or near his best? Let’s suppose that you own 120 CDs of his entire output. As part of a spring-clean, you decide to keep only those pieces that, according to received wisdom, reveal a truly satisfying creative artist. What would you hang on to? The obvious candidates are the Faust symphony, the odd tone poem, the piano concertos, a sprinkling of Hungarian Rhapsodies and Transcendental Etudes, most of the Années de Pèlerinage, the Legends, some of those late spectral jottings, the variations on Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen – and, towering above everything, the B minor Piano Sonata. Those pieces would take up roughly five CDs. So you’d need a suitcase to carry your discarded Liszt to the Oxfam shop.

But what if you were really ruthless and kept only music judged to be worthy of comparison with the peaks of the romantic repertoire, such as Schumann’s Fantasy in C or the Chopin Ballades? In that case, as they say on Building a Library, it’s time to say goodbye to Faust, the concertos, the tone poems and many shorter piano pieces. A double album consisting of the sonata and the very finest solo piano works would convey the essence of Liszt’s inspiration as it’s usually understood. About 2 per cent of his output, in other words.

Now let’s indulge in a little alternative history and imagine that the B minor Sonata has just been unearthed in a German library and is the only trace of Franz Liszt. The world would immediately recognise the greatest piano sonata composed since the death of Schubert. People would ask: what other masterworks by this towering figure remain to be discovered? Surely such a man was capable of changing musical history, not with haphazard experiments in form and tonality, but with ‘proper’ symphonies and sonatas of Beethovenian stature. Given what Alfred Brendel calls the ‘total control of large form’ and ‘blend of deliberation and white heat’ in the B minor Sonata, what other wonders might this Liszt have worked?

These hypothetical questions may sound far-fetched, but I don’t think certain critics have ever forgiven the real Franz Liszt for writing only one big work in which everything — melody, form, counterpoint, texture — fits together. To be sure, they can understand why pianists are so drawn to the showpieces. One minute semiquavers are falling on to the keyboard like raindrops, the next a strutting bel canto aria is surrounded by fist-flying octaves: Liszt certainly knew how to press the ‘encore!’ button. But the applause is usually for the performance, not the music, whose attempts at profundity strike discerning audiences as empty or vulgar.

Is that fair? Most great composers dabbled in cheap music. No one thinks any the worse of Beethoven because he wrote a jaw-droppingly vulgar ‘Battle Symphony’. Then again, no one confuses it with his real symphonies. With Liszt, however, not only is there lots of irredeemable rubbish, but elsewhere it’s difficult to distinguish the tinsel from the magnificence, as Schumann put it. The same piece can sound noble or overblown, heartfelt or syrupy, depending on the interpretation. You could never say that Liszt is ‘music better than it can be played’: no composer of piano music is so completely at the mercy of the performer.

But this is good news as well as bad, because it means that the right pianist can transform music that has dropped out of the repertoire. And that pianist isn’t necessarily the one with the quickest fingers: it’s someone who puts his or her technique entirely at the service of the music. We expect nothing less when we’re listening to Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms and lots of lesser composers. But we tend not to care if poor Liszt is manhandled — partly, I suspect, because we’ve decided that he was a hypocritical ‘showman’.

One of the greatest services we can do him this year is to forget the historical figure of the womanising Abbé, and listen to performances of his work by artists who grasp the simplicity that often lies at its heart. Wilhelm Kempff and Alfred Brendel come to mind, but they recorded mainly the highlights. It’s also worth seeking out Stephen Hough and Steven Osborne in less well-known music — and Leslie Howard, too, who takes a piece like Litanies de Marie, written off as pious sentimental junk, and lets its deliberately modest melody soar. We have to play our part, too, by retuning our ears so we aren’t offended by a musical vocabulary of tremolo chords and tinkling harp arpeggios that we’ve been taught to despise.

Break through that barrier, and you realise that the apparent emptiness of Liszt’s profundity — not only in the piano music but also in oratorios such as The Legend of St Elizabeth — can convey intense calm and a renunciation of self. Of course you won’t find it in the Hungarian Rhapsodies; in fact, one of the infuriating things about Liszt is that you can never be sure where the gold is buried. But the search is worth the effort, and the bicentenary should remind us that the musical world has put it off for too long.

To mark the Liszt bicentennial, Stephen Hough plays Liszt’s First Piano Concerto with Ivan Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall on Sunday 16 January.

Comments