Architects and politicians have a lot in common. Each seeks to influence the way we live, and on account of that both, generally, are reviled. But architecture is more important than politics. Unless you are an anchorite or a polar bear, it’s unavoidable. And it lasts longer.

The best architecture affects our mood. Exaltation, if you are lucky. And the worst influences our behaviour: a riot with burning Renaults, if you live in a French banlieue. But, as a new exhibition at the Wellcome Collection suggests, architecture may also, in one way or another, affect our health.

At ground level, this is quite obvious. Damp, foul air, extreme temperatures, bad drains, structural collapse, fire risks, asbestos and socially hostile environments can all, alas, be experienced in buildings. And these are good for no one’s health.

But in the 1970s a belief took hold that design itself was the culprit. It was in 1972 that Erno Goldfinger’s infamous Trellick Tower was approaching completion, so forbidding a building that even one of his own assistants described it as ‘Stalin’s architecture as it should have been’. The same year we reached a high tide of revulsion against this building type and the debased culture it was thought to encourage: lobbies littered with cigarettes, syringes, bottles, the reek of urine, lifts not working, pensioners isolated 300 feet above the ground, smashed lights and blocked rubbish chutes.

And it was in 1972 that an American architect called Oscar Newman published his book Defensible Space. Newman argued that a lot of this horror, presented in vox pop at the Wellcome, might be mitigated if individual dwellings were made characterful and common areas could be under popular surveillance. These ideas fed into urban geographer Alice Coleman’s controversial Utopia on Trial of 1985. Coleman had done her homework. Her analysis of more than 4,000 council blocks in south London saw correlations between the levels of litter, graffiti, vandalism and the number of flats per entrance.

‘Bad design does not determine anything,’ Coleman wrote, ‘but it increases the odds against which people have to struggle to maintain civilised standards.’ Her conclusions — removing overhead walkways and creating gardens for ground-floor properties, for example — were implemented by Thatcher and proved both popular and effective (they reduced burglaries by 55 per cent on an estate in Westminster).

The architectural establishment rounded on her. Some pointed to the garden city estates developed between the wars that were riddled with crime — evidence that seemed to undermine Coleman’s hypotheses. Others rightly observed that the most egregious facts of estate life are down to poor maintenance and inadequate security, which are beyond the remit of the designer. It’s a chastening fact that the expensive afterlife of buildings is uncosted in most budgets. We might see a happy revolution in building design if that bias changed.

‘Salus populi suprema est lex’ (the health of the population is the first law), Cicero said. And there’s no gainsaying that intelligently designed dwellings accessible to all would be a defining characteristic of utopia. Yet the absurd irrationalities of human behaviour make architecture’s design-wellbeing axis annoyingly non-linear.

When they were clearing the Festival of Britain site in 1950, families protested about being evicted from fetid slums and rehoused in tower blocks. Today, no one needs persuading that housing needy people in tall buildings has been an atrocious calamity. Yet take a walk along 57th Street and it’s very obvious that the rich enjoy living in tall buildings very much indeed. Can the explanation just be the presence of 24-hour security and hot tubs? Possibly yes. Can the explanation be design? Possibly yes again.

Or take Belgravia. I doubt an Eaton Square mansion has ever made anyone sick with anything other than envy. On the other hand, comfortable, sanitary and serene Belgravia has produced fewer artists than Glasgow or Liverpool. And, actually, isn’t Brixton psychologically healthier than Mayfair?

So much of the early rhetoric of the modernists concerned health. Le Corbusier came from a Swiss culture where ‘tourisme sanitaire’ was a way of life. The Montreux-Vevey littoral was a ‘jardin de cure mondial’. It was in Vevey, where monkey-gland treatment was perfected, that he built a house for his mother. This health culture might have been a pseudoscience of heliotherapy, miasmas and emanations, but this clinical aesthetic found its way into the architectural mainstream.

The most interesting parts of Living with Buildings are the social and architectural histories of slums and brave new buildings, all illustrated by diverting documents. But the question of the hospital itself is not shirked. The artist Giles Round, inspired by Aalto’s multicoloured Paimio Sanitorium where the architect construed the entire building to be a medical instrument, has looked at colour as therapy. By contrast, there is the cottage hospital where folksy notions of domesticity were held to be healthful, as they probably are. That’s the principle used by Maggie’s Centres, where the not-normally-folksy Frank Gehry, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers have made careful and thoughtful contributions to the wellbeing of cancer patients by designing humane, amiable spaces. And Rogers’s successors at Rogers Stirk Harbour have created a potentially mass-produced air-portable clinic that’s ‘simple and economic to build’. The 1:1 model upstairs will be sent to a real-world location when the exhibition closes.

Geneviève Heller explained in Propre en ordre (Clean and Tidy), a highly original 1979 study of Swiss health culture, that by about 1930 ‘new forms of decoration… reconciled sanitary needs with aesthetic wants… equally applicable to the houses of the rich as to the poor’. The hated Corb’s ‘machine à habiter’ had to have chef d’oeuvre plumbing, fresh air, central heating and lots of sunlight. And so, too, did those of his less adroit imitators.

One of these was Goldfinger, a Corb pupil whose infamous tower blocks in Poplar and Notting Hill are, depending on your view, heroic or despicable. Goldfinger is something of an eminence noir at the Wellcome. To disarm early criticism, he went for a well-publicised stay in one of his own flats ‘to taste my own cooking’, which he found most satisfactory. Goldfinger’s buildings, present here in a beautiful drawing, gave J.G. Ballard a model for the sick dystopia he describes in High-Rise (1975).

All of this is at the Wellcome, but so, too, is an agenda. While faint praise is offered to Berthold Lubetkin’s Finsbury Health Centre of 1938, a modernist masterpiece, Living with Buildings is on the whole anti-modern in sentiment. The tragedy of modernism’s failure is a recurrent theme. But as Reyner Banham explained in his 1969 book, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment, it was technological innovations in making things more habitable — developments in air-conditioning, lifts, waste disposal — that made the modernist experiment possible in the first place.

Some resistance might remain to these experiments, but we can agree that those rearguard architects still using classical orders are like the Japanese soldiers who still occasionally turn up in the Philippines. In any case, if we are discussing health, car usage, and therefore pollution, in anti-modern Poundbury it has increased.

Inevitably, Grenfell. Here, Potemkin cladding led to catastrophe. A good corrective would be to leave it as a charred stump, rather as, on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm, the Gedächtniskirche remains a ruin as a reminder of Bomber Harris’s unhealthy destructive urges,: the hohle Zahn (hollow tooth), they call it. Who knows? Such a shocking sight in London might be inspirational.

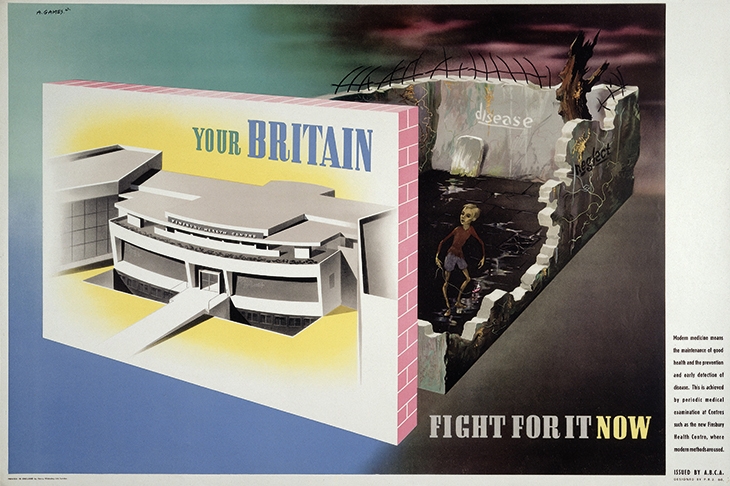

Churchill said that we shape our buildings and then our buildings shape us. And at the Wellcome Collection there is a fine 1942 poster by Abram Games, last master of the drawn lithograph, that shows a disgraceful slum giving way to a shiny, optimistic new modernist building. Churchill objected to it. But then Churchill objected to the Festival of Britain because he thought it Soviet.

As I was saying, blame the politicians.

Comments