If you had to choose an obvious place to look for clues about what will happen in the coming year, it probably wouldn’t be the lush, green, watery tropic wilderness of Mount Borradaile, West Arnhemland, in the Northern Territory, Australia, hard by the sizzling blue reaches of the Arafura Sea.

For a start, this lost, ancient chunk of Oz is almost empty – there are far more saltwater crocs than cars, and far more rare and exquisite wading birds than people. How can this lovely place speak of modernity? Of the future? And yet if I am right, the clues hidden in this Edenic wilderness suggest that we are about to see our lives entirely overturned – in a way that once happened in Arnhemland. The rocks may even illuminate our ultimate fate.

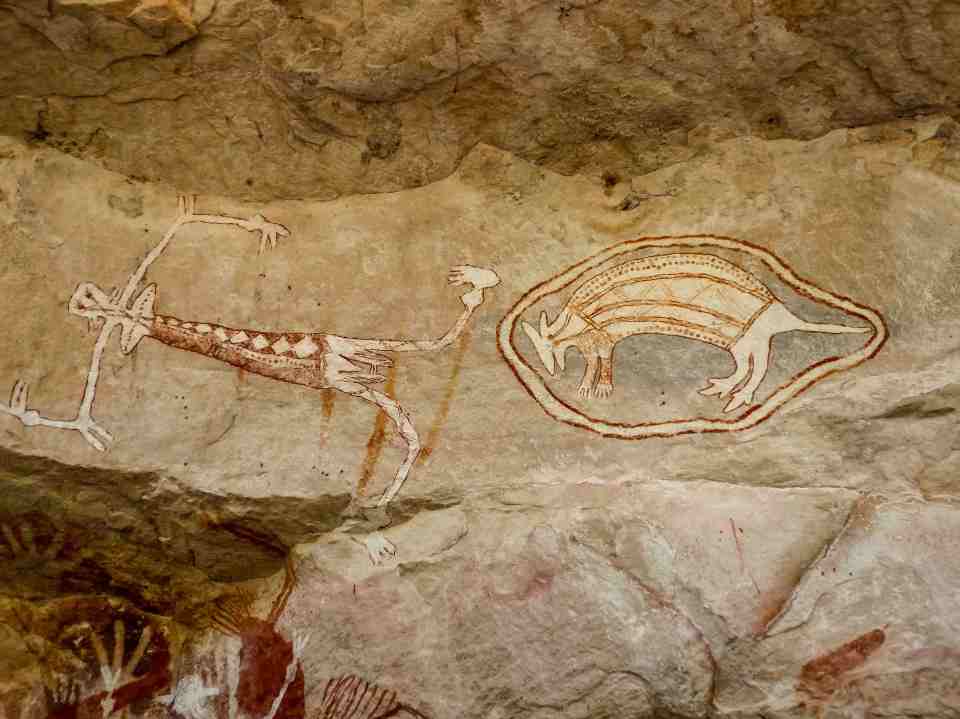

To understand, check out the rock painting above. What you are looking at is an example, from Mount Borradaile, of ‘contact art’. This is art created by alarmed Aboriginal painters as they responded to their first shocking glimpses of Europeans or non-Australians: sailing their coasts, landing on beaches, hunting the feral buffalo.

The earliest examples of contact art, on this coast, depict the boats of the Macassans: sea-slug harvesters from Sulawesi, in modern Indonesia. Over ensuing years the examples of contact art grow in number, as the Europeans arrive and contacts become more frequent – and intrusive. Imposed upon the traditional rock art motifs – wallaby, goanna, catfish, rainbow serpent – we see pearl luggers and steamboats (as in the example above), churches and houses, warships and soldiers’ wigwams, elegant pistols and Martini-Henry rifles.

But much of the art is jarring, eerie and disjointed. One painting shows a British man holding a rifle; yet he is holding it like it is a spear he aims to throw. In another the European man is on a horse – yet the horse looks like a kangaroo. There is throughout a poignant dissonance: because these haunted paintings show fearful humanity encountering something alien, strange, highly advanced – and utterly unknowable. The artists yearn to understand what they are seeing, but they fail. It is beyond their ken. They reckon horses are kangaroos.

What does this have to do with the modern world, and the coming year? For the answer, we must go to Silicon Valley.

In recent weeks rumours have been growing that the latest iteration of artificial intelligence, a ‘large language model’ called GPT4, will be arriving in the first months of 2023. GPT4 is the successor to another large language model called GPT3.

GPT3 was born in 2020. And, as I have written before, it is quite spooky enough. It is a huge ‘neural network’ which responds to natural language and is able to write good poetry on demand, or advertising copy, or blog posts, or short stories in the style of Jerome K. Jerome. GPT3 can also create music, produce artwork, do excellent coding, make movies, craft decent jokes, write pithy tweets – and multiple other things. Recently a sibling of GPT3, a LLM designed by Meta/Facebook, started defeating humans at Diplomacy – a game requiring deep verbal skills and the ability to deceive.

Despite all this, almost everyone has agreed that GPT3, while impressive and uncanny, is not really Artificial General Intelligence (by definition, that’s when artificial intelligence equals human intelligence, in versatility and speed). Many still insist that AGI is a long way away.

Is it? Consider this. Whereas GPT3 was fed humongous screeds of random data (all of Twitter, Reddit, Wikipedia etc) GPT4 goes much further. It has apparently been fed the entire internet. Indeed, when training GPT4, the AI-wranglers apparently ‘ran out of internet’ and fed the growing monster billions of images, sounds, anything. Putting it numerically, GPT3 has 175 billion ‘parameters’ (which are akin to human brain cells). GPT4 is rumoured to have 100 trillion. It might therefore be 500 times bigger than GPT3.

A computer that can 100 per cent convincingly walk, think and act like a human will be human to us. Or, of course, superhuman

The implications of this are profound. Models like GPT3 were so good they made engineers at Google wonder if they were sentient. A very recent spin-off of GPT3, a talkative bot called ChatGPT, is so persuasively clever, informative and articulate it has got people saying ‘this is as important as the first iPhone’ and ‘this is the biggest moment since the invention of the internet’. Elon Musk, a founder of OpenAI, is tweeting that ChatGPT is ‘scary’ and ‘we are not far from dangerously strong AI’.

What on earth, then, will GPT4 or its inevitable successors be like? GPT4 might be so powerful it will appear entirely and flawlessly intelligent to everyone; that is to say, it will breeze through the Turing Test (which checks if computers can pass as humans in conversation) and accelerate away.

At that point, the question as to whether the computer is ‘conscious’ will become a secondary issue, something for philosophers to mull over in dusty libraries – like, say, the centuries-old mind-body problem. For everyone else, the world will be transformed.

A computer that can 100 per cent convincingly walk, think and act like a human will be human to us. Or, of course, superhuman. We will definitely have to give it rights. Many lonely people will want to befriend the robot. GPT4, or 5, or 6 will be the perfect companion, with just the right words to console, amuse, advise. Think Alexa, but with the wit of Oscar Wilde and the wisdom of Jane Austen. I wonder if we will have an urge to worship these machines. Because a supersmart, puissant, omniscient, near infallible mind will seem very much like a god.

The arrival of AGI will likewise alter how nations deal with nations. One recent online rumour claims that the reason Joe Biden hastily slapped his radical ban on the export of AI tech to China is that he was given warning from Silicon Valley of what was shortly coming down the line, and how powerfully malign the new AI could be. Especially if it fell into the hands of bad actors.

The arrival in our midst of AGI – next year or next decade – will therefore be an epochal moment in human history. An inflection point. For the first time we will share the world with another, alien, superior intelligence, one that thinks in ways we cannot comprehend. It will ride a horse – but we will squint and see a kangaroo. It will carry a gun – and we will presume it is a spear.

And our ultimate fate? For a glimpse of that, let’s go back to West Arnhemland.

A few decades after the first contact art appeared in Arnhemland, the Aboriginal people were largely swept from their homelands by the economic forces and political changes brought by European settlers. But not everyone deserted these silent red canyons and bright lilied waterways. In the 2000s, the last native speaker of the local Amurdag language, Charlie Mungulda, returned to the Mount Borradaile rockfaces to paint a symbolic and final hand, a scarlet print which says remember us, because we were here. With this ritual, he signalled an end to 50,000 continuous years of Aboriginal art in West Arnhemland. Nothing has been painted in Mount Borrodaile since. Nor will it be.

Comments