My campaign to bring back real life

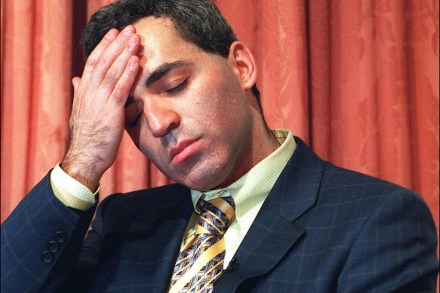

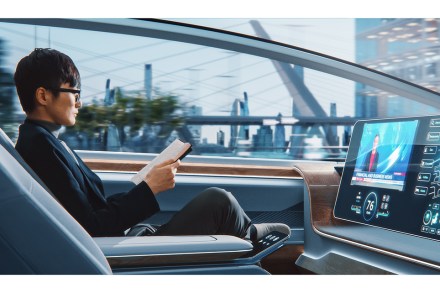

A new book by an American writer, Christine Rosen, details the way in which we are losing touch with the real world: the one we evolved in, as opposed to the virtual one. All the scrolling and texting means we’re forgetting the look and feel of life unmediated by screens. The book is called The Extinction of Experience, and if we get more anxious year by year, then it’s not just wars or the cost of living, Rosen suggests, but because we’re grieving for the real world, whether we know it or not. I definitely know it. I’m Gen X, so I grew up without the internet, yet like other