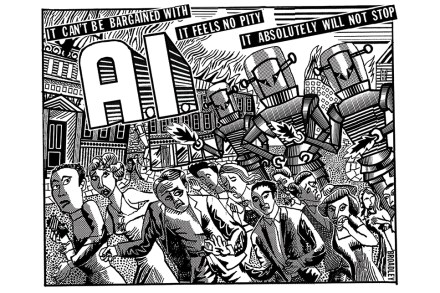

Will we even notice if AI replaces screenwriters?

We are edging into the third month of the strike by the Writers Guild of America, called because of shrivelling residual royalty payments from streaming movies and TV, as well as concern about AI such as ChatGPT being used to generate story ideas – and indeed to write scripts. Hollywood’s screenwriters have now been joined by the 150,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild, which was demonstrated very visibly by the cast of Oppenheimer walking out of its UK premiere last week. ‘We are all going to be in jeopardy of being replaced by machines,’ said union president Fran Drescher. Susan Sarandon has said of AI: ‘I would hope that