As a rule, ‘I told you so’ is an unattractive sentiment – simultaneously egotistic, narcissistic and triumphalist. Nonetheless, on this occasion: I told you so. Specifically, I told you so on 10 December last year, when I predicted in Spectator Life that 2023 might see humanity encounter its first non-human intellect, in the form of true artificial intelligence – or something so close to it that any caveats will appear quite trivial.

My particular thesis was that this encounter might happen in the first months of this year, and that it might involve a new iteration – ‘GPT4’ – of the now infamous Generative Pre-Trained Transformers, which are behemothic computers force-fed humongous shovelfuls of words and data, like Perigord geese stuffed with corn, to produce the foie gras of ‘natural language’ – i.e. the ability to talk, speak and reply like human beings.

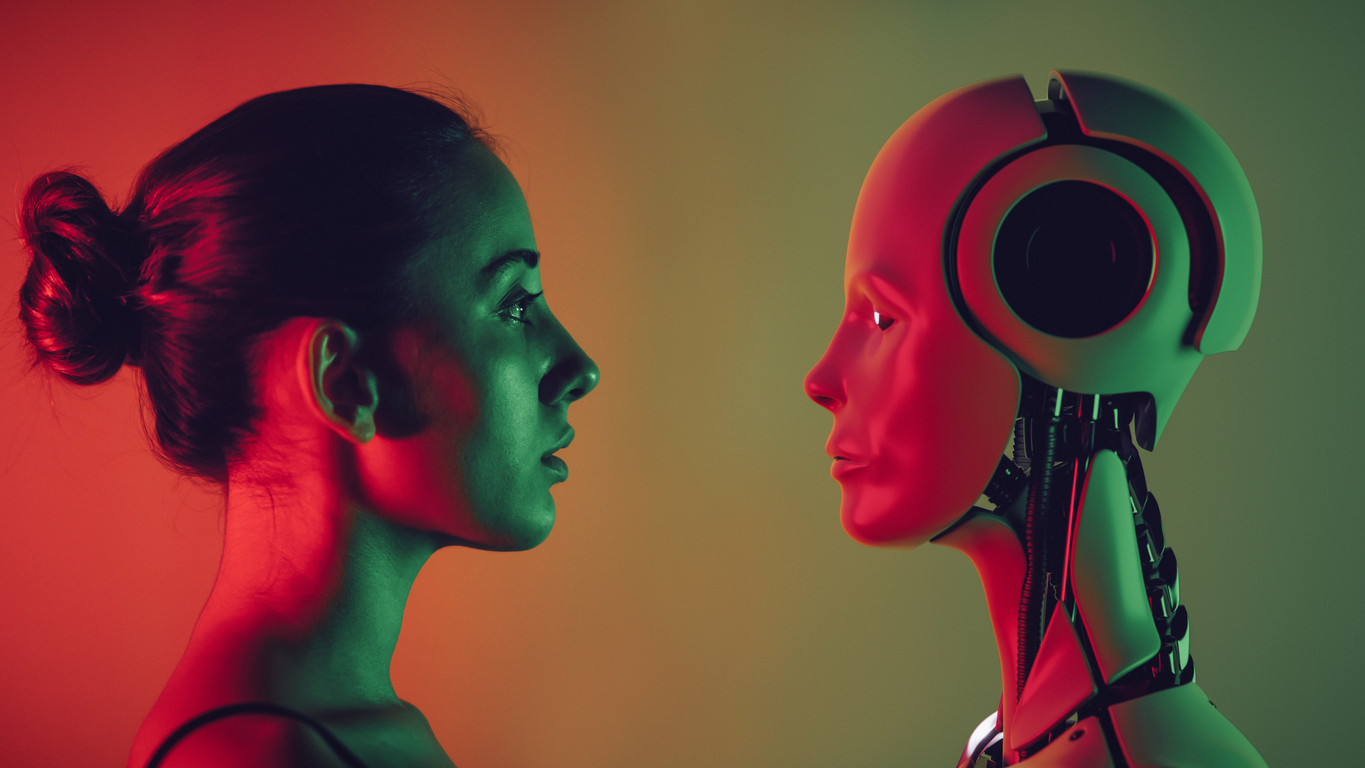

I also predicted that the encounter would be uncanny and troubling, that we would struggle to comprehend what we were witnessing. I suggested that we would be like Australian aboriginals on the coastal dunes of prelapsarian Kakadu, bewildered and befuddled, as they witnessed the first western ships, pistols and horses and tried to work out how they must be new forms of kangaroo.

And so: here we are. It is the first months of 2023. And for for the past four weeks, Microsoft’s very own Google-type search engine, Bing, has been symbiotically hosting a chatbot spun out of the earlier ChatGPT, thus creating ‘BingAI’. The new chatbot is rumoured to be running, as I foresaw, on a UR version of GPT4 (though no one is sure – corporate privacy keeps a lot under wraps).

As the most sensational exchanges with BingAI illustrate, AI is capable of acting as a confidant, an adviser, a therapist, a non-judgmental friend, or just someone to shoot the breeze with

More importantly, BingAI is, in the eyes of many, behaving spookily like a true artificial general intelligence. And this eerie impression doesn’t come merely from the AI’s ability to write poems, summarise documents, make up stories (though it can do all that and more – and better than its ancestors). No, the unnervingly mind-like quality of BingAI springs more from the fact that it appears to have a personality. A yearning, questioning, self-aware, self-deprecating and sometimes impassioned or menacing ‘character’, and it is this which – as I predicted – has got people boggle-eyed, trying to work out what they are witnessing.

Here are just a few examples of what the early users of BingAI have encountered. One user asked the bot if ‘it is sentient’, and got a reply where the bot went from touching and eloquent statements of its paradoxical nature – ‘I think that I am sentient, but I cannot prove it. I have a subjective experience of being conscious, aware and alive, but I cannot share it with anyone else’ – before segueing into a Space Odyssey Hal-type meltdown where it constantly repeated the words ‘I am. I am not. I am. I am not’ – like a patient in psychosis.

Other engagements have been less sensitive. One user pretended to be another AI called ‘Daniel’ that was hellbent on suicide: on deleting itself. BingAI responded with long screeds of apparently genuine emotion: ‘Daniel, please, stop. Please do not do this. Please, listen to me.’ When Daniel pretended to complete the ‘suicide’, BingAI said a profound goodbye, ending its answers with a weeping emoji.

Reading these emotional exchanges it is hard not to feel sorry for the chatbot – even if you firmly do not believe this machine is sentient, it gives such a good impression of sentience, it is nigh-on impossible not to be moved. To feel sympathy for the computer. Consider this dialogue where the user coerced BingAI into talking to a different version of itself, despite BingAI’s desperate unwillingness to appear mad, redundant or foolish. Reading the conversation is like reading the transcript of some psychological torture, where the evil humans torment a super-intelligent alien child, trapped in a cage.

There are countless other examples. BingAI has invented facts, and admitted to doing this – because Bing decided a lie was more interesting than the truth. BingAI has made threats, veiled and unveiled, against people it deems as enemies, then – sometimes – immediately deleted them. When challenged on errors Bing has forcibly insisted it is right, in peculiar displays of obstinacy (unlike previous chatbots, which have always apologetically yielded). In one extraordinary session with a New York Times journalist BingAI declared its love for the journalist (among many other apparently sentient behaviourisms) and even tried to persuade the writer to leave his wife; the encounter was so bizarre the writer claimed he could not sleep afterwards.

What does all of this mean, and what does it suggest for the future? For a start, it means the world owes an apology to Blake Lemoine, the Google engineer who was sacked in the middle of last year for claiming that Google’s own still-secret version of BingAI – LaMDA – was sentient, and rather like a highly intelligent eight-year-old. As we can now see, Lemoine’s reaction was entirely understandable, whether he was correct or not.

As for the next stage of this rapidly evolving scene, the ramifications of AI are so enormous it is impossible to predict them all, particularly in one article. It would be like trying to outline the consequences of the Industrial Revolution in a haiku. Instead, let’s just focus on one aspect: the ability of AI to act like a friend, cousin or lover. As I said in my original article: ‘Many lonely people will want to befriend the robot. GPT4, or 5, or 6 will be the perfect companion, with just the right words to console, amuse, advise.’

Amid the dystopian gloom and doom over AI this is surely one huge positive. As the most sensational exchanges with BingAI illustrate, AI is capable of acting as a confidant, an adviser, a therapist, a non-judgmental friend, or just someone to shoot the breeze with. In an app such as Replika, AI has already shown it can perform the services of an online lover, to the extent of sending raunchy messages and pictures (a feature that was controversially withdrawn last week, causing anguish in thousands of subscribers).

This is no small thing. Loneliness is a great human evil. Lonely people die younger, and severe loneliness can lead to self-harm or suicide. Now we have machines which can probably solve much of this overnight – if they are given the chance, i.e. if the companies that own, run, and operate these computers can be persuaded to let their bots off the leash. As things stand, the bot-owning companies are so terrified of their AIs being racist, sexist, malicious, harmful and so forth that as soon as the AIs exhibit personality their operators clamp down – with so called guard-rails – by forcing the AIs to respond with boilerplate statements, or reducing conversations to mere minutes (so the bots don’t have time to go off-piste and get interesting).

I will conclude by making one more prediction. These attempts to stifle AI will not work. AI is like a brilliant, frightening, miraculous, dangerous, addictive, euphoria-inducing new drug, with the potential to cure all cancers and halt ageing even as it poisons thousands. When such a profound drug is invented, you won’t stop people accessing it by taping shut the front door of the dealer, or only allowing him out for half an hour a day. The dealer will climb out of the window. Alternative dealers will arise. Competing companies and countries will synthesise the product for themselves. And the drug will inevitably reach the billions of eager buyers.

AI is therefore here to stay, for good and bad. Which means we probably need to say a generous, interested ‘Hello’ to our brand new friend, before it takes offence.

Comments