For most people today radioactivity is synonymous with bright yellow warning signs, explosions and poison. But there was a time when radioactivity was revered, not feared. And when it seemed like everyone in Britain was clamouring for more of it.

In the late 19th century Wilhelm Röntgen discovered a previously unknown form of powerful radiation that was invisible to the human eye and so mysterious that he simply named it ‘X’. Working from Röntgen’s findings, the French engineer and physicist Henri Becquerel identified the phenomenon of radioactivity – both as a concept and as a force – and Marie Skłodowska Curie would later give it a name.

Radium also began to be used for decoration

In December 1898 Curie identified two new materials, which she named polonium and radium. These natural radioactive elements were shown to be capable of change: spontaneously turning into totally different substances without any intervention. Uranium, for instance, decays into thorium, which in turn becomes radium. After that comes radon. Eventually, after multiple transformations, the uranium decay chain ends with a ‘stable’ element – lead – which emits no more radiation.

Wherever deposits of uranium rocks are found you can find natural sources of radioactivity. The gas radon is released into the environment after escaping through natural cracks in the ground. Radium can also be found in rocks which water trickles over: in which case it infuses the water with radioactivity.

After Curie’s discovery, facilities and treatments began to spring up, all based on the theory that exposure to radium in small doses – most commonly administered by drinking radium laced water or by breathing in radioactive radon gas – was beneficial. It was believed that radiation triggered a chain of physiological reactions that boosted the immune system.

You could have a radium mud bath in Harrogate, eat radium bread in Bath – ‘Britain’s Radium Spa’ – and drink radium water in Buxton’s Pump Room. And, if the fancy took you, you could even take a bottle of Buxton Natural Mineral Water home with you. The official guide to the town presented this as: ‘A British Water for British Whiskey!’

There were also a wide range of products and services that were aimed at the general consumer. There were health products such as the O-Radium Hat Pad (‘whenever you are wearing your hat, you are subjecting your hair to beneficent rays’). At Boots the Chemists, you could acquire Sparklet’s ‘Spa-Radium Bulbs,’ which turned tap water into carbonated radioactive water, a Nu Ray Radium Lamp (a combination of radioactive materials and a household electric lamp) or Radior radium toiletries (‘guaranteed to contain actual radium and remain radioactive for 20 years’).

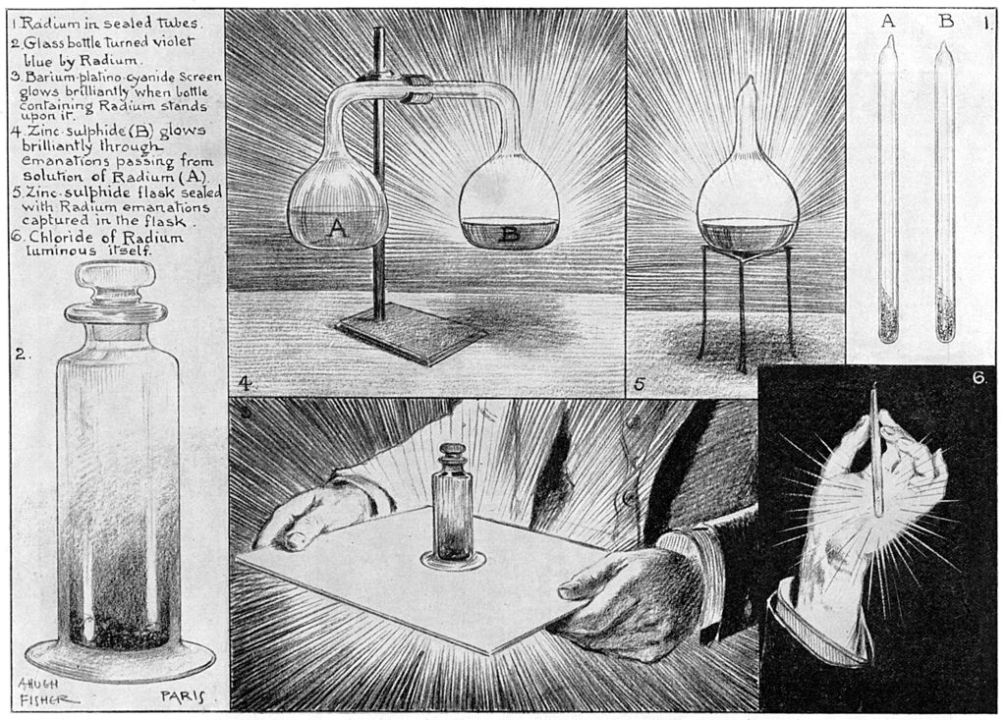

Radium also began to be used for decoration. When turned into radium chloride, the material glows in the dark, an effect caused by the radiation agitating nitrogen that is naturally present in the air. This vibration creates a buzz of energy, perceptible as a shimmer of light. Adding a sticky substance to these salts made a self-luminating, glow in the dark paint. One of the first experiments with radium paint was for the costumes for the 1904 Broadway production Piff! Paff! Pouf! The glowing paintwas also put on the costumes of The Pony Ballet, a vaudeville act of eight teenage girls who specialised in a style of dancing said to imitate horses’ movements. They performed to a piece of music written especially for the play: the ‘Radium Dance’ and were a huge hit.

By 1915 radium paint was in widespread wartime use, on aeroplane instruments, compasses and binoculars.

It was also recommended that members of the armed forces buy a glow in the dark radium wristwatch. Wristwatches were more useful in warfare than pocket watches, but they were dangerous if you had to light a match to check the time, giving away your position to the enemy. Watches with luminous dials therefore quickly became a must-have gadget and companies such as Ingersoll, J.C. Vickery and Mappin & Webb produced hundreds of radium watches during the first world war.

Wearing a radium watch became a fashion that spread through wider society. It has been estimated that over four million glow-in-the-dark watches were produced in the United States by 1920.

Demand for these watches continued to increase, which in turn led to more women being hired to paint the radium onto watch faces and dials. By the mid-1920s, it was estimated that there were more than 120 plants across the US employing more than 2,000 women.

It was a coveted job – until they started dying. It emerged that workers at these factories had been encouraged to adopt a special technique. This involved ‘pointing’ the brush – using their mouths to get a fine point – so they could paint the tiny dials with fewer mistakes. Later, it was estimated that each painter might have ingested between a few hundred to a few thousand micrograms of radium in a year.

The case of the Radium Girls led to investigators learning a great deal about the behaviour of radium inside humans. It was discovered that it did not pass straight through the body, as had been previously thought, but accumulated in various organs. Because there was nowhere for it to go, it continually irradiated the surrounding cells. By 1933 medical associations began to withdraw their approval of radium for internal use and its use in consumer products and popularity in spa towns began to wane. Which brought to an end Britain’s own brief love affair with radioactive products.

Comments