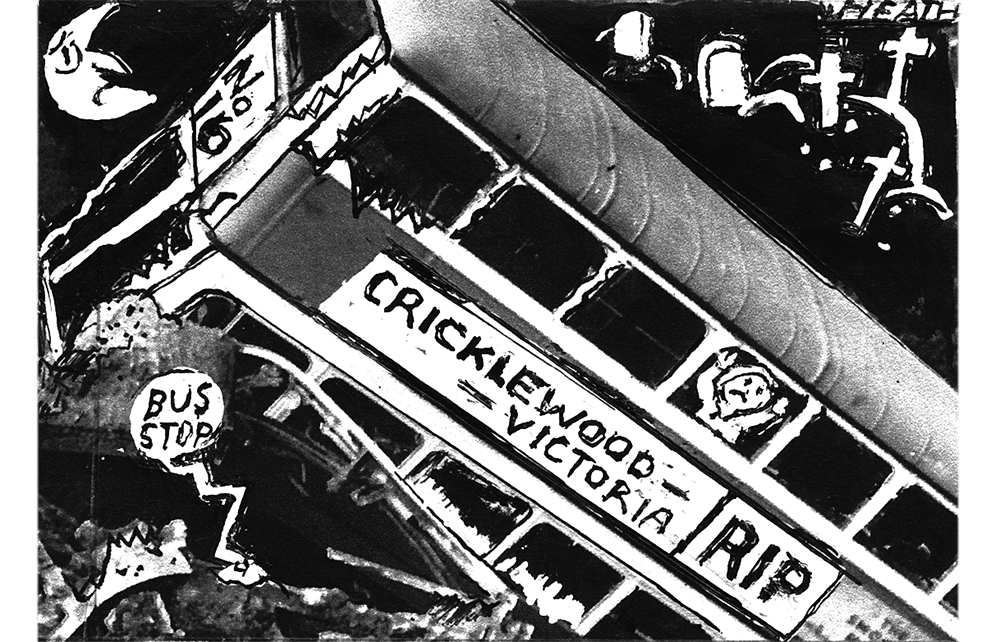

At the former Chiswick Works in west London, I recently celebrated the Routemaster’s 70th birthday. I owe my existence to this majestic mode of transport. My mum was a conductress on a Routemaster – the No. 16 – which cut a merry swathe from Cricklewood to Victoria, right through the centre of London. My dad, like a lot of young Irishmen, had arrived in London in the 1950s to help rebuild a city still recovering from the second world war. Every morning, he’d catch the first bus from his digs off the Edgware Road to various building sites. One morning he got chatting to the young clippie, and married her a few months later. ‘Open the front door,’ he’d say to me years later, ‘and the whole world’s outside.’

For families like ours, who didn’t own a car, the ‘whole world’ began at the bus stop. Routemasters arrived at the end of our street to take us where we wanted to go. Passengers still pine for their perfect confluence of form and function. Each one was more than a mere bus, it was a mobile community. Its open back platform allowed the locals to jump on and off swiftly.

My mum wasn’t the only family member who worked on the No. 16. She and Uncle Ken, conductor and driver respectively, were London Transport’s only brother-and-sister bus crew. Except when Uncle Ken was paired with his sister Gert or his sister Joyce. So for my family, On the Buses was less a sitcom and more a documentary.

On a Routemaster, the conductor ran the show. The best ones were like good publicans, greeting their regulars with a quip and a smile. They all had their rules and my mum’s included ‘Never take a fare from a nurse or a nun’. She also acted as a vital conduit between passengers who’d just arrived from Ireland or the Caribbean and needed somewhere to live, and other passengers who might have a spare room.

After dark, the sight of an approaching Routemaster was like a warm, welcoming lantern that had come to carry you home. Although you were never sure exactly when it was going to arrive, I believed – still do – that if you stared hard enough up the road, your bus would miraculously appear.

From an early age, I was hopping on without adult supervision. Kids round our way were all brought up with that ideal combination of love and neglect, so our mums neither knew nor cared where we went during school holidays. The first place was usually Franklin’s newsagent, where we could buy a 25p ticket called a Red Rover and enjoy a day’s unlimited bus travel on Routemasters.

Bus travel lost its magic when Routemasters, along with conductors, were phased out. They were replaced by lumbering one-man buses. Passengers were delayed because the driver had to take all the fares, then again because, without the open platform, they were trapped until the doors were released.

Socially and environmentally, London has suffered ever since. At Chiswick Works, I felt extraordinarily lucky. Without the Routemaster, I wouldn’t be here. And without it, as a child, I wouldn’t have been anywhere.

Comments