Historians in Ireland occupy a public role – unlike in Britain, where those with an inclination towards the commentariat usually migrate to America. This is perhaps not surprising in a country where public intellectuals are exemplified by Stephen Fry and philosophers by Alain de Botton. Ireland presents a more demanding prospect, where, ever since the days of Conor Cruise O’Brien, historians have colonised the public sphere with influential newspaper columns and regular debates on television. Indeed, when the national TV station began broadcasting in the early 1960s, it featured a discussion programme called The Professors, all of them historians (and one or two usually a bit the worse for wear).

The scale and pace of change in Ireland since the mid-1990s is seismic

Diarmaid Ferriter currently carries the flag for the historian-as-commentator, and does it with considerable élan. He is also far too hardworking to abuse the hospitality room. His punchy columns in the Irish Times are required reading on the issues of the day, and a stream of substantial books have dug deep into the modern Irish experience, covering revolution, civil war, social change, sexual behaviour and most recently the Irish border. His magisterial study of the 20th century was called The Transformation of Ireland – a title also applicable to his latest volume, where the word ‘revelation’ seems rather odd in the context.

Or maybe not if it means, rather than a stunning coup de foudre, the unveiling of something that was there all the time. Ferriter tells us that his earlier use of ‘transformation’ now seems provisional, and the new book, beginning in 1995, ambitiously charts the upheavals of economic boom and bust, the coming of uneasy peace to Northern Ireland, the crumbling of the social and political power of the Catholic Church, and above all the diversification of a society transformed by immigration: Gort, County Galway, where Yeats spent his summers, is now largely inhabited by a lively Brazilian community attracted by the local meat-packing industry. Tread softly.

Ferriter is too good a historian not to admit that many of these changes are rooted further back. Economic transformation had much to do with Ireland’s entry into Europe in 1973; the 1998 Good Friday Agreement was part of a process that began with the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 and the Downing Street Declaration of 1993, not to mention the Hume-Adams rapprochement of the 1980s; the challenge to the Catholic Church’s domination was arguably ignited by the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s. But the scale and pace of change since the mid-1990s remains seismic.

Ferriter profiles it through omnivorous reading, using journalism as intensively as public records; his analysis is enlivened by much quotation from contemporary fiction (another boom area). It is all delivered in rapid-fire style, with swift and sometimes discombobulating changes of gear. Readers may be surprised by beginning a section on education and finding themselves segued into the etiquette of thong-wearing (or not) in the south Dublin teen dating scene. But Ferriter maintains a beady eye on the challenges of writing contemporary history at a time when the sources of knowledge and record are themselves changing exponentially.

Beneath the dizzying statistics profiling wealth, inequality and soaring population-levels lie certain continuities. These include the stable structures of government which enabled the country to withstand potential constitutional crises, the threat of violence spilling over the border with Northern Ireland, and (in the immediately preceding period) the rule of a Taoiseach as corrupt as Charles James Haughey. The era covered by this book saw the proportional representation electoral system deliver a series of pragmatic coalition governments, the most symbolic being that which crossed the old Civil War divide between Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, which persists. Meanwhile, the partial domestication of Sinn Fein continues, in the Republic, with Mary-Lou MacDonald courting middle-class reassurance, despite skeletons rattling loudly in the closet, and maintaining the old Sinn Fein trick of stealing clothes from the ‘ridiculously fractured’ left.

Ferriter emphasises the resilience of centrist politics as well as the liberalised culture which saw the advent (by referendum) of equal marriage in 2015 and the partial legalisation of abortion in 2018. But he also points out the refusal of church authorities to co-operate with official investigations into sex abuse, the resilience of a narrow clientelist politics at local level, the idiosyncratic approach of senior politicians to tax evasion and cash in brown envelopes, and the abysmal approach to planning and the built environment. Social analysis of Dail members may not present an Irish equivalent of the entitlement profiled in Simon Kuper’s Chums. But landowners and rentiers are strikingly predominant, and women spectacularly under-represented, while the worlds of the law and the higher civil service sustain a Chum-esque trajectory through select private schools and the older universities.

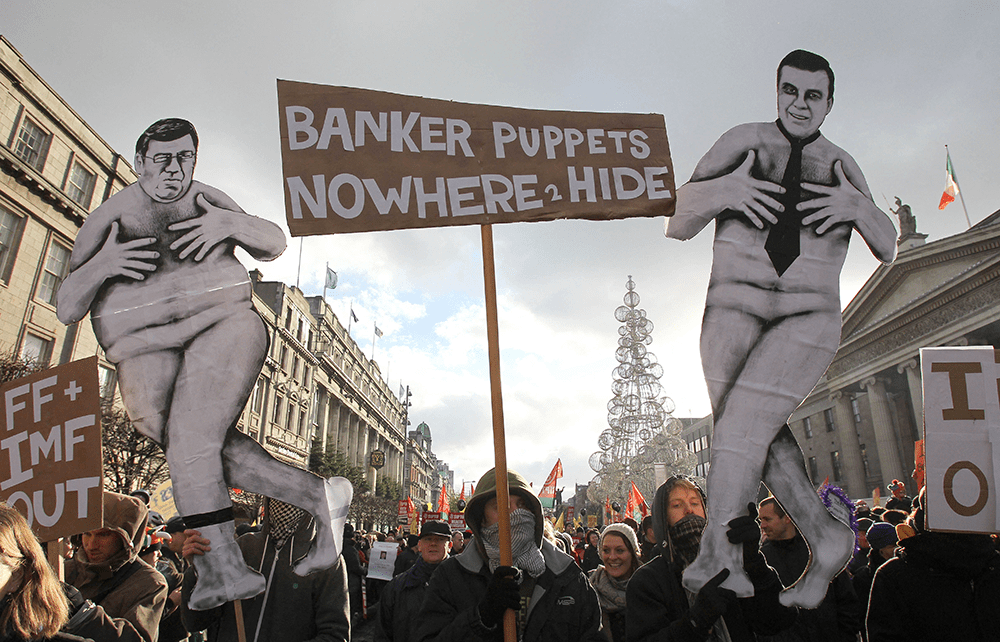

On a wider level, Ireland’s vaunted ‘globalisation’ is much in evidence. The American input into the lead-up to the Good Friday Agreement contrasts notably with the fury of earlier British governments at transatlantic ‘interference’. Economically, the importance of inward investment from US giants such as Dell and Apple into Ireland’s corporate-tax-friendly workplace, along with the major pharmaceutical companies, bulks large. The Irish department of finance sniffily rejected the description of ‘tax haven’, but it was not far off. Globalisation also conferred large dollops from EU structural funds (Ireland remained a net beneficiary until 2006), and a monetary policy linked to the eurozone instead of sterling. Hyper-globalisation brought its risks, culminating in the crash of 2007, which dramatically exposed the government’s ludicrously negligent approach to ‘light touch regulation’ of the banking economy. Vast loans, sustaining and inflating a fragile property bubble, were managed by unlovely figures such as Sean Fitzpatrick of the Anglo-Irish Bank. It all had to end in tears.

And so it did, with draconian measures enforced by the European Central Bank and a national plunge into ‘negative equity’. Ferriter is good on the general lack of contrition, the relatively speedy bounce-back of certain sectors, and the way that bondholders were protected at the expense of little people. Taoiseach Enda Kenny’s insouciant analysis (‘People simply went mad borrowing’) spread the blame rather too thinly. The conspicuous consumption satirised by Ireland’s own Thorstein Veblen, the popular economist David McWilliams, somehow survived; ‘Wonderbra economics’, the massively entitled Expectocracy, RoboPaddy (‘no place is too far-flung to prevent him buying off the plans’) and Breakfast Roll Man, living out of convenience stores, are with Ireland still. So are record levels of inequality, an apparently insoluble housing crisis in Dublin (the Irish approach to social housing is distinctly un-European), and a public health system (or lack of it) in free fall. The many pages Ferriter devotes to this are among the most excoriating in the book.

The unevenly distributed Irish recovery (‘Celtic Comeback’) throws into sharp relief a number of key themes. One is the decisive shift in foreign-policy axis towards the EU and away from the neighbouring island, reinforced by the fallout from Brexit. To the stupefaction of some British flat-Earthers, Ireland’s European allies lined up in unanimous support against the various confused and shambolic attempts to deny that a land border between the UK and the EU now existed, and that the fragile stability of Northern Ireland since 1998 was heavily compromised – a development blithely unforeseen by a series of spectacularly dim secretaries of state for that unlucky province. (The signal exception, Julian Smith, was sacked following Brexit rows.) In the Republic, clouds are also gathering over the reception of refugees, and immigration in general.

Ferriter ends with a consideration of the recent commemorations marking the centenaries of the Irish revolution, partition and the civil war – pointing out that many of the issues that lay behind those distant upheavals persist, ‘re-shaped’, today. He also admits that, in an age of social media, ‘high priest historians are not the exclusive arbiters of historical narratives’. Too true, but for the moment they seem the safest bet going.

Comments