Ian Williams has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Somewhere in the bowels of the Foreign Office, civil servants are still working on the government’s ‘China audit’. The report was commissioned by the new Labour government to ‘assess trade-offs in the UK-China relationship’ and to ‘ensure consistency across government, business and academia towards engagement with China’. Little is known about its workings or who’s being consulted. Instead of bringing clarity, the process is deepening confusion, and there are worrying reports that the audit has been pared back to support Keir Starmer’s ‘pragmatic’ approach. All the while, there have been a series of troubling events that demand extreme caution about Beijing.

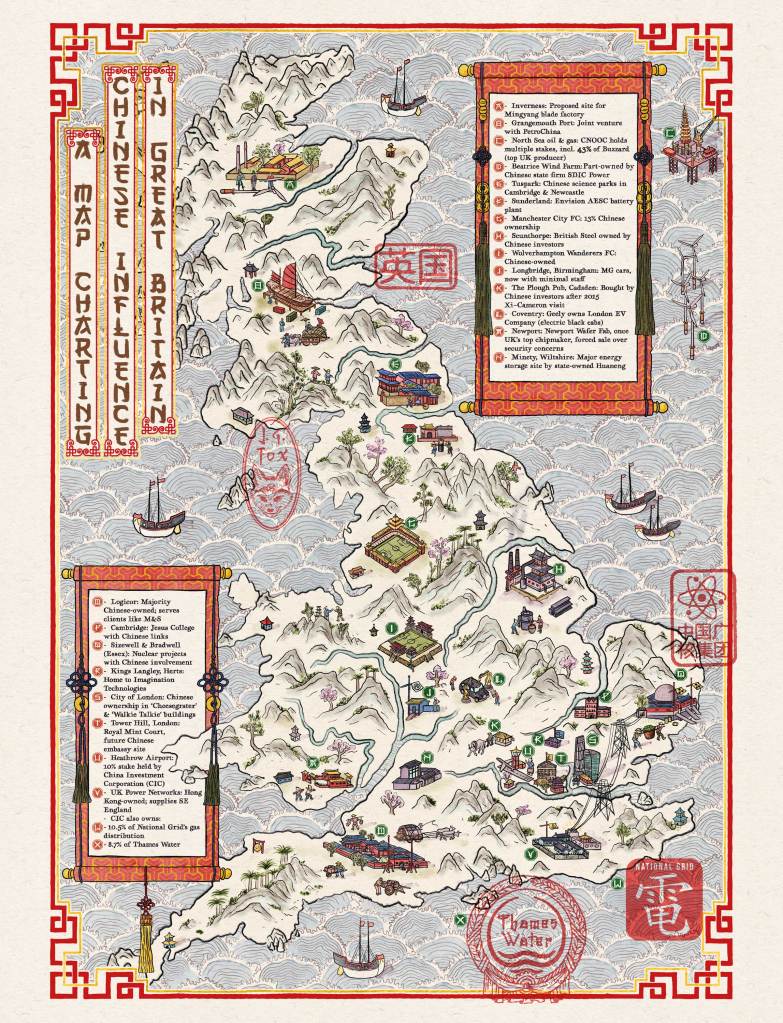

The British Steel debacle is only the latest. Jingye, the company’s opaque owner, run by a former Chinese Communist party (CCP) official, is accused of trying to shut down the Scunthorpe plant by sabotaging its blast furnaces. Whether or not Jingye was doing the bidding of its political masters in Beijing, Chinese officials quickly jumped to its defence. The Chinese embassy lashed out at critical British MPs, accusing them of an ‘arrogance, ignorance and a twisted mindset’.

It’s not known what the auditors make of all this, but ministers are not waiting around. Chancellor Rachel Reeves and Energy Secretary Ed Miliband have both visited Beijing to woo investors. Miliband signed a memorandum of understanding on a ‘clean energy partnership’ with China, while Reeves argued for a deeper economic partnership between the two countries, saying it would be ‘very foolish’ to disengage. Starmer himself is backing China’s bid to build a giant new embassy at the old Royal Mint at Tower Hill, despite intelligence agencies’ warnings about the site’s proximity to sensitive underground communications cables.

A thorough China audit should focus on which parts of Britain and its economy are most exposed to entities linked to the CCP. Grangemouth, Britain’s oldest oil refinery, due to close by the end of last month, is half owned by PetroChina. The loss of the refinery, the only one in Scotland, could erode energy security to the benefit of China: Mingyang, China’s largest wind turbine manufacturer, wants to build a factory near Inverness. And turbine blades are not just dumb pieces of steel. They are complex, connected devices governed by algorithms and software that remain under the control of the manufacturer. Last year, Mingyang was rejected by Norway over security fears.

Chinese firms have multiple investments in North Sea oil and gas. The fully state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation has boasted that it contributes more than a quarter of the UK’s oil production. It also has a substantial stake in the Buzzard field, one of Britain’s highest producers.

The American Enterprise Institute estimates the value of Chinese investments in Britain between 2005 and 2024 at £80 billion. These are spread across numerous sectors. China General Nuclear Power Group – sanctioned by America on security grounds – has a 27 per cent stake in the Hinkley Point plant. Geely Auto owns London EV Company, which makes electric black cabs. Chinese investors have stakes in Heathrow airport (10 per cent), the National Grid’s gas distribution network (10.5 per cent) and Thames Water (8.7 per cent). Groups controlled by Li Ka-shing, a Hong Kong-based industrialist, own UK Power Networks, which operates electricity distribution infrastructure across south-east Britain, and 75 per cent of Northumbrian Water.

A third of Chinese donations to UK universities are from firms linked to the military or blacklisted in the US

Envision, a Chinese battery firm, owns the AESC gigafactory in Sunderland and is building a second plant there. A vast energy storage project in Minety in Wiltshire is funded by China’s Huaneng company. Tuspark, a Chinese science park operator, has set up parks in Cambridge and Newcastle. Chinese investors also hold a large property portfolio in the City of London, including the Leadenhall Building (‘the Cheese Grater’) – and a majority stake in Logicor, a major warehousing and logistics firm, which serves companies including M&S.

Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation owns MG cars, the (former) British marque. Production has shifted entirely to China and just 46 workers remain at the Longbridge plant to inspect the imports. Chinese investors bought the Plough pub in Buckinghamshire, after David Cameron and Xi Jinping had a pint there during Xi’s 2015 state visit. A Chinese consortium purchased a 13 per cent stake in Manchester City football club, another Xi destination during that visit. In 2017, Imagination Technologies, which designs cutting-edge mobile graphics processors, was bought with Chinese money after assurances that the investment would be passive. Last December, an employment tribunal ruled that Ron Black had been unfairly dismissed as chief executive after blowing the whistle about the CCP’s attempts to ‘steal the technology’.

Then there’s academia. The thinktank Civitas estimates that up to £156 million in research tie-ups and other donations was received by British higher education institutions from Chinese sources between 2017 and 2023. A third came from companies linked to the Chinese military or blacklisted in the US. One particularly generous donor to Cambridge is Huawei, which was barred from Britain’s 5G network because of security concerns. On the plus side, the China Forum is finally being shut down by Jesus College after heavy criticism of the lack of transparency of its funding and its parroting of CCP propaganda.

Britain’s largest China studies centre is King’s College London’s Lau institute, whose biggest donor is a Hong Kong tycoon with CCP links. King’s insists all donations are subject to a strict ethical review, but has rejected Freedom of Information requests about how the review is conducted, claiming that releasing such information would be ‘prejudicial to international relations’.

The government says its emerging China policy will allow Britain to ‘co-operate, challenge and compete’, and that ‘strategic’ or ‘sensitive’ investments will come under closer scrutiny. Good luck defining those. It’s hard to separate security concerns from economic opportunities when the CCP routinely uses trade, investment and market access as means of coercion. All Chinese companies, whether nominally private or officially state-owned, are required by law to serve the interests of the CCP on security and intelligence.

The China audit was supposed to herald a new era of realism in British politics. But how, for example, can the government square its net-zero obsession with the dangers of using Chinese tech? It may be impossible to hit climate targets without using Chinese renewables. Yet that would be to hand over control of the de-carbonised grid to the CCP. If the audit is ever published, an appropriate cover illustration would be a Trojan horse.

Comments