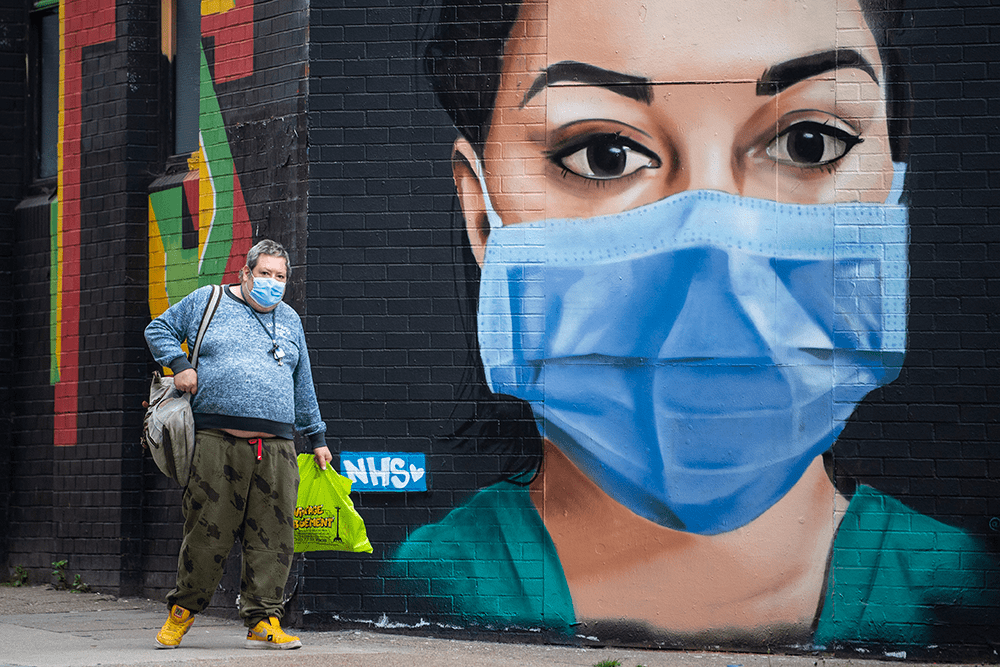

It was at about this time, five years ago, that the workers at my (then) local farm shop began wearing plastic bags on their feet, over their trainers. This was because of a report somewhere that said the Covid virus hung about on the ground and then leapt, with great agility and cunning, on to people’s shoes, from whence it swiftly decamped to your bloodstream and killed you.

We were still rubbing raw alcohol on to our hands wherever we went, if you recall, because whatever you touched harboured the virus. You couldn’t actually go in the farm shop but had to give your orders to the staff who manned a table out front, from which you were instructed to stand one metre back. People with short arms had difficulty reaching their groceries. In the supermarket we were instructed to queue up three yards distant from the person in front, but there was no similar injunction against standing alongside someone else, presumably because the virus did not understand how to travel from side to side but floundered, like a Dalek confronted with stairs. People in the queue who coughed were given the sort of looks of abhorrence which hitherto had been reserved for practitioners of the more extreme avenues of paedophilia. And then we went home with our potatoes, and stayed home.

Me – I loved it. Partly because I didn’t have to travel to London to be told things by awful people, partly because it felt Ballardian and I have always adored J.G. Ballard… but mainly because we lived in the countryside with a nice garden. ‘Go back to your filthy tenements!’ I would shout at the families who fled the city for their one-hour walk in the countryside each week, all masked up and trepidatious, pointing at cows, gawping at sheep.

Covid, or our bizarre reaction to it, has done more to destroy this country than the Luftwaffe could have dreamed. Not the buildings – the people. It first destroyed the fairly fundamental social contract that suggests that if we wish to buy stuff, we ought to earn it by working. Then it destroyed what had seemed a rather agreeable Conservative government and a prime minister whose approval ratings were unimaginable by today’s standards. For a lot of us it shattered the belief we had in our medical clergy, who got to run the show for a while – disastrously – and indeed made us doubt experts generally. Perhaps that was the only good thing. But the damage done to our children’s schooling was not so good, nor the complete wrecking of the economy for a generation and beyond. And while lockdowns were intended to protect us from Covid, they did not do so and left us at the mercy of other much more serious diseases. And vaccines? Well, we shall see. I suspect the long-term health stats won’t be too pretty.

Arguably the worst thing it did was destroy the UK as a functioning nation and tilt the balance of what economy remains to the extent that it feels like we will be in debt for perpetuity. It did this first by reminding us that our homes are, by and large, quite pleasant and it is a bit of a drag to leave them, especially if there’s something good on the box. It’s certainly a drag to leave them to do anything so recherché as work. Figures out this week reveal that the UK is by far and away the country in Europe most smitten by the working-from-home virus: an average of 1.8 working days a week are spent at home here, compared with 1.3 around the world. Only the reliably stupid Canadians exceed our figure.

The pandemic has done more to destroy this country than the Luftwaffe could have dreamed

Pre-Covid, I had nothing against the concept of working from home, especially as it would free up office space for flats. But because of Covid, working from home did not quite mean working from home: it often meant not working from home either. Prior to Covid, 5 per cent of people worked from home: it is now 40 per cent in the private sector and 48 per cent in the public sector. The more you are paid, the more likely you are to work from home.

And it was during Covid that the balance between the private sector and the public sector tilted decisively in the latter’s favour, with an increase in the number of public sector jobs and a very rapid rise in public sector pay when private companies were cutting wages or going tits up. There is now a 7 per cent gap in median weekly earnings between the two sectors. Each year, that privileged elite who earn money from our taxes also take an average of four more days of holiday and almost twice as many sick days as those who actually generate revenue for our country.

What we are left with, then, is a public sector which is absent from the office, bloated and comparatively overpaid, and feeling itself entirely justified in making outrageous pay demands (‘30 per cent for the “junior” doctors!’) because, after all, we banged our saucepans together for them, didn’t we? Or at least some halfwits did. And then there’s the rest of the population, either low-waged or no-waged, resenting the prospect of doing any work at all because the rewards are so negligible compared with sitting at home and watching Bargain Hunt.

The question is why we have been so badly affected compared with the rest of the world – because we have, without doubt. Roughly 700,000 people have been lost to the jobs market since the start of Covid: that has happened in no other rich country. Many of them suffer chimeric illnesses. And once again Covid lurks at the heart of our post-lockdown psychology: that illness has, for some, become almost aspirational and they expect the same cosseting they got in 2020. That, matched with extravagant benefit payments and an inflated public sector, is why this country, literally and metaphorically, is not working. And behind this lies that spiky virus and what it did to our minds.

Comments