Time was, the Christmas shopping season used to last a week or two. Now it drags on for months. Never mind wage inflation – what about present inflation? The whole thing is like a gigantic poker game, where the stakes are raised remorselessly every year.

How did Christmas mutate into this orgy of rampant consumerism? Step forward the man who invented Christmas: Charles John Huffam Dickens Esquire.

The story of how Scrooge recovers his lost innocence speaks to something deep in all of us, a yearning for lost childhood

It’s a bit of an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas – but like the exaggerations of his novels, it articulates a basic truth. Folk were making merry at Christmas time before Dickens came along, but it was his emotive fiction which established Christmas in the English imagination as the apotheosis of family life, the most important festival of the entire year.

Only Dickens had the power to do this. It was a testament to his unique skill as a storyteller, his unrivalled ability to create (as Peter Ackroyd put it) ‘A world in which everyone felt at home, yet a thousand times brighter than the real thing.’ But in 1843, the year he wrote A Christmas Carol, he was a man under pressure, worried that his success might be on the wane.

Dickens’ early bestsellers had established his reputation as Britain’s finest novelist, bringing him commercial success and vast critical acclaim. His byline brought a circulation boost to any publication, but he wasn’t merely a man of letters – he was a modern celebrity, the first literary superstar. His opinion was solicited on every matter – his public readings drew huge crowds.

Yet while The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby and The Old Curiosity Shop, all written in his twenties, had proved immensely popular, his latest novels, Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit, hadn’t done so well. In the autumn of 1843, his publishers, Chapman & Hall, warned him that unless sales picked up, they’d have to reduce his monthly stipend.

For Dickens, this news could hardly have come at a worse time. He was making good money, but he was supporting a large extended family (including his feckless father, whose spendthrift ways had landed the family in a debtors’ gaol when Dickens was a boy). And now, to make matters worse, his wife Catherine was expecting their fifth child. Driven by economic necessity, as much as artistic inspiration, Dickens set himself six weeks to write a Christmas bestseller. That book was A Christmas Carol, and its immortal characters – Scrooge, Tiny Tim et al – have become as much a part of our Christmas iconography as the Shepherds and the Wise Men.

When Dickens sat down to write A Christmas Carol, Christmas was still a relatively low-key affair, and many of its festive trappings were conspicuous by their absence. It was merely the first day in a twelve-day holiday, which reached its climax on 5 January, the night before Epiphany, aka Twelfth Night.

The marginal significance of Christmas was reflected in Anglican liturgy. Advent was an austere affair, a time of quiet contemplation rather than celebration. Christmas (Christ’s Mass) wasn’t an important feast day in the Anglican calendar. Since the Reformation, Puritans had regarded it as an unwelcome remnant of Roman Catholicism, ‘a Popish festival with no biblical justification,’ (as Professor Peter Gaunt, of the University of Chester, puts it). There was no mention of Christmas in the Bible other than the Nativity, and Protestants regarded any rite without scriptural precedence as insufferably Papist (the C of E was a lot more Protestant in Dickens’ day).

However, by the time Dickens embarked on A Christmas Carol, such attitudes were changing. The new Oxford Movement had begun to agitate for a less Puritanical C of E. Christmas Trees (introduced by George III’s German wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg, and popularised by another German consort, Prince Albert) were becoming increasingly prominent, partly due to German immigrants to Britain’s industrial cities. In December 1843, the same month that A Christmas Carol was published, the director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, Sir Henry Cole, sent the first recorded Christmas Card.

Twelfth Night was still the main festival, but although it involved lots of feasting (with a ‘Lord of Misrule’ instead of Father Christmas) there was no tradition of exchanging gifts, a nuisance for shopkeepers. For mercantile Victorians, Christmas was a far more attractive prospect, and as the greatest journalist of his age, a reporter, editor and columnist par excellence, Dickens had an acute feel for the Zeitgeist, a keen sense of which way the wind was blowing.

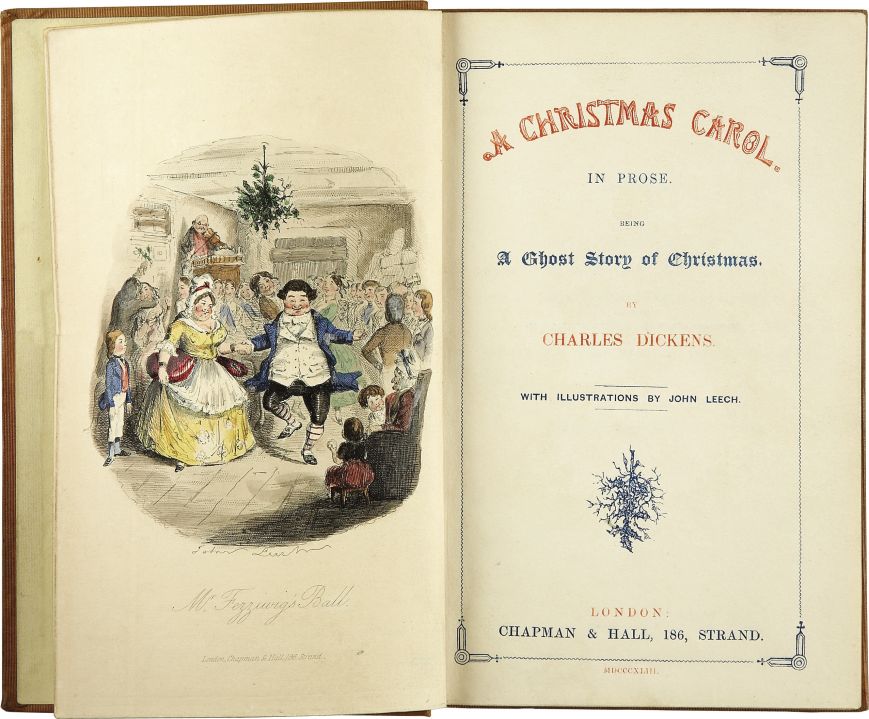

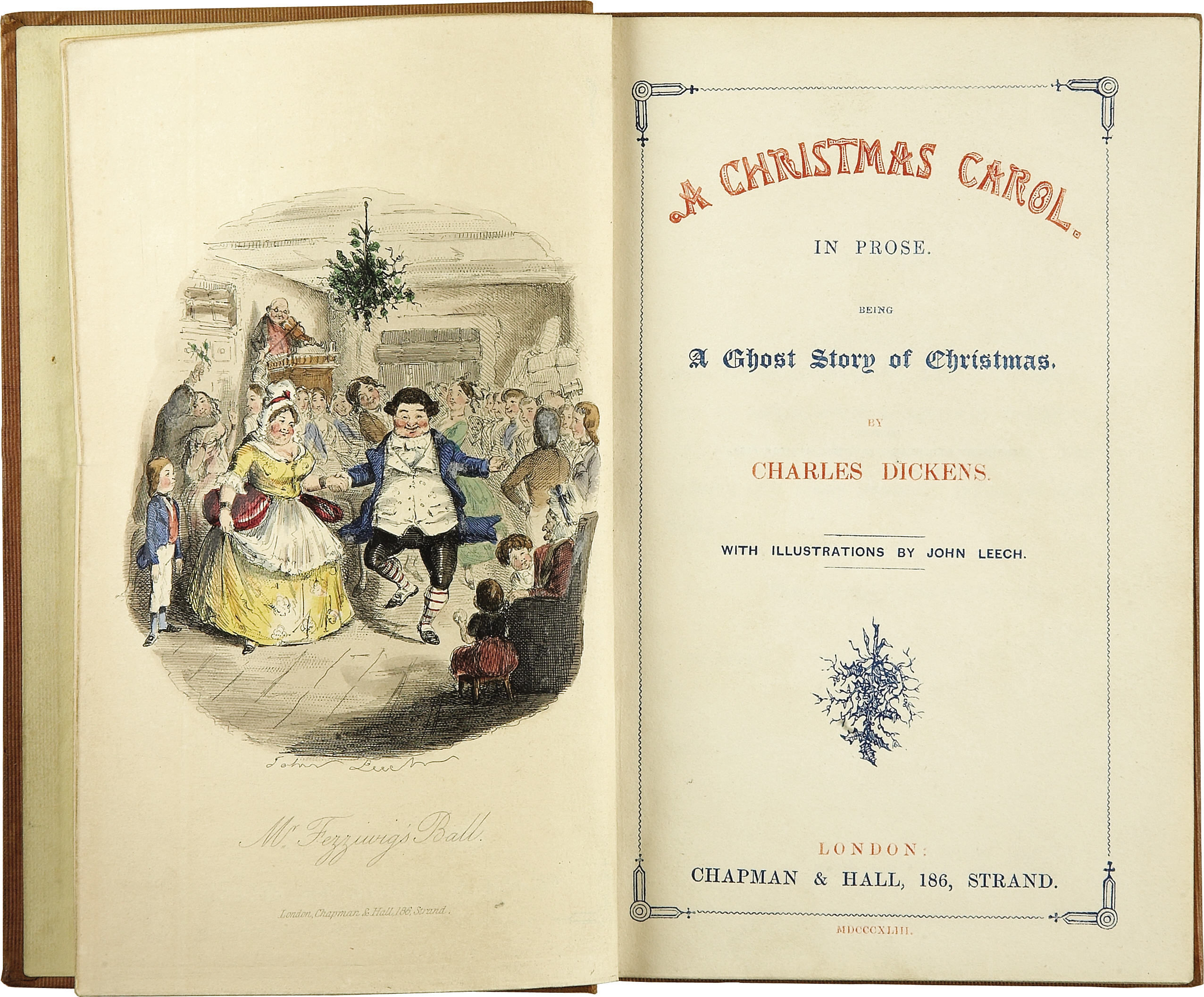

Always a hands-on author, with an instinctive flair for marketing, Dickens oversaw the design of A Christmas Carol, and he made sure that it was specifically promoted as the ideal Christmas present. With a burgundy cover, embossed in gold, and hand-painted colour illustrations, it was an instant hit, selling six thousand copies in the first few days after publication.

Dickens had to take legal action against the publishers of a bootleg edition (always a good sign) but despite such healthy sales, those colour illustrations reduced his profit margin, and so he didn’t make nearly as much money as he’d anticipated. He’d hoped to make £1,000 – worth around £143,000 today. Instead, he made £230, the equivalent of about £33,000 in modern money – not bad for six weeks’ work, but not enough to transform his fortunes.

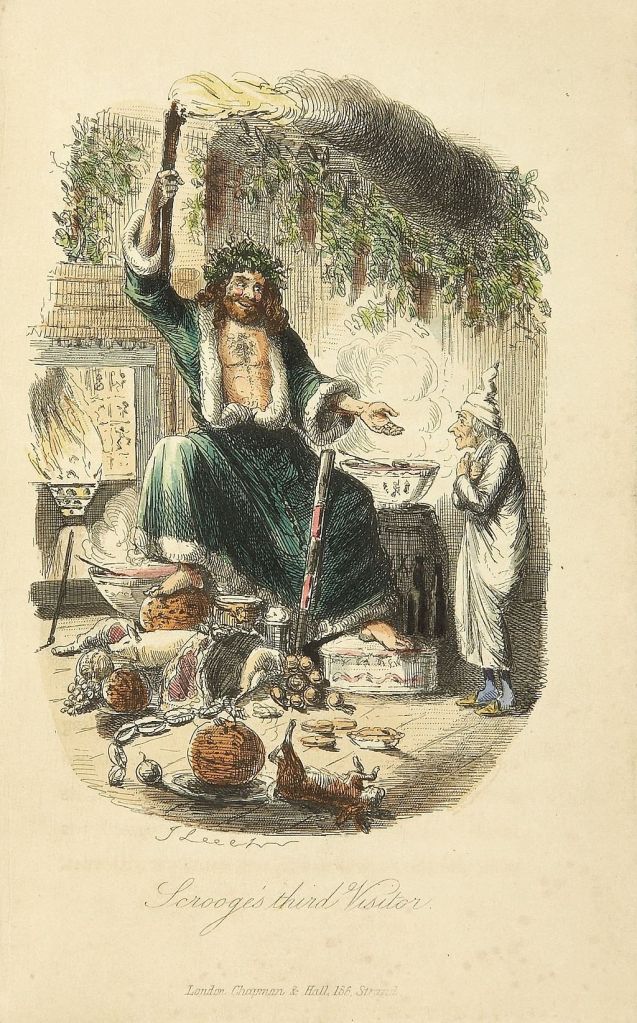

These expensive illustrations may have been bad for business, but they did wonders for the book’s reputation. A Christmas Carol was a thing of beauty, in stark contrast to the cheaply produced – and often pirated – ‘Penny Dreadfuls’ of the age. After all these years, John Leech’s engravings remain a source of fascination, a precious glimpse of Christmas past. The most interesting one is his ‘Ghost of Christmas Present’, a Father Christmas prototype, but dressed in green – an indication of his Pagan connection with a woodland world of holly, conifers and mistletoe. Even more surprising, to modern eyes, this proto-Santa is slim and youthful, rather than rotund and elderly, with a sleek brown beard, a bare hairy chest and an impressive six-pack.

For the next few years, Dickens wrote a Christmas story every year – The Chimes, The Cricket on The Hearth, The Battle of Life and The Haunted Man – but although they all did fairly well, none of them came close to matching A Christmas Carol, and it’s easy to see why. The beauty of Dickens’ story lies in its simplicity. In his archetypal tale of a sinner being shown a nightmare vision of his future, he fashioned a timeless parable of salvation (childless and alone, Scrooge is an everyman for folk who feel left behind at Christmas time – at first the villain of the piece, belatedly, you realise he’s a victim).

Happily, Dickens’ book is still widely read (my teenage daughter studied it for her English GCSE), but its biggest impact in recent times has been on screen and stage. The screen adaptations are almost too numerous to count, cementing Scrooge as one of the landmark roles for male actors of a certain age. Albert Finney, Patrick Stewart and Rowan Atkinson have all had a go, and who can forget Michael Caine, gloriously upstaged by Kermit the Frog as Bob Cratchit in The Muppet Christmas Carol? From where I’m sitting (on a saggy sofa strewn with Quality Street wrappers and other Christmas detritus) the 1951 film, starring Alistair Sim, remains the definitive dramatisation. Last time I looked, it was still free to view on YouTube – look out for Hattie Jacques and a youthful George Cole as young Ebenezer Scrooge.

Donald Duck and Fred Flintstone have both wrestled with the role (for Walt Disney and Hanna-Barbera respectively) but the biggest glut of adaptations in recent years has been onstage. This Christmas, you can see Simon Russell Beale as Scrooge at London’s Bridge Theatre (directed by Nicholas Hytner), Adrian Edmondson for the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, and Robert Bathurst in Dolly Parton’s Smoky Mountain Christmas Carol, at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on London’s South Bank.

And that’s not all. There are currently productions of A Christmas Carol in Bath, Bolton, Bristol, Buxton, Chesterfield, Coventry, Doncaster, Exmouth, Liverpool, Portsmouth, Salisbury, Sheffield, Windsor, Wilmslow, Woking and Kingston-upon-Thames (profuse apologies to any places I’ve missed out). As The Old ‘Un, the wise old diarist of the Oldie magazine, observed, ‘Until a decade ago, Dickens’s tale of redistribution was seldom known onstage. Since then, it has become the second-most popular Christmas tale – after Matthew, Mark Luke and John’s greatest Christmas story of all.’

But why? Why are Britain’s theatres embracing Scrooge and co. like never before? I believe it has a lot to do with austerity. In today’s hard times, pantomime feels too superficial, too frivolous. A Christmas Carol provides the respite of a happy ending, but it doesn’t shy away from suffering. Its depictions of illness, grief and poverty are painfully real (as in all his greatest fiction, Dickens mined the hardship of his early life to fuel this fable – like Scrooge, he had a sister who died in childhood, of tuberculosis).

Yet I reckon there’s also a deeper reason, and the clue is in the title. As its name suggests, A Christmas Carol has a profound religious subtext, rooted in the Christian creed of repentance and forgiveness. The moral of A Christmas Carol is that it’s never too late to make amends. The proliferation of Christmas carols indicates that, while we may be losing our appetite for churchgoing, we haven’t yet lost our appetite for the Good News of the Gospels.

Who among us doesn’t want to mend our ways, and become a better person? The story of how Scrooge recovers his lost innocence speaks to something deep in all of us, a yearning for lost childhood – a state of grace which, like Ebenezer Scrooge, we’ve long since left behind. As Dickens declares, ‘It is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty founder was a child himself.’ His sentimental story may have opened the floodgates for today’s kitsch, avaricious Advent, but its central message – that Christmas is a time for kindness and companionship, endures.

William Cook is the theatre critic of the Oldie, and the author of Morecambe & Wise Untold, and One Leg Too Few – The Adventures of Peter Cook & Dudley Moore.

Comments