Stuart England did not do its anti-Catholicism by halves. In the late 1670s and early 1680s, a popular feature of London’s civic life were the annual Pope-burning pageants which took place every 17 November to commemorate the accession of Elizabeth I and the nation’s historic deliverance from the forces of international Catholicism. In 1679, one contemporary estimated that 200,000 people watched the spectacle, as a series of floats wound through London’s thronged streets bearing oversized effigies of Roman Catholic clergy, nuns, Jesuits and the Pope to be tipped into a bonfire at Temple Bar or Smithfield with lavish firework accompaniment. In some years, the Pope’s effigy would bow to the crowds, thanks to some elaborate stage mechanics; in 1677 it even screamed as it burned — in reality the sound of the cats imprisoned inside being consumed by the flames.

This brutal street theatre was one aspect of a period of political, religious and social turmoil known as the Exclusion Crisis, which centred on whether parliament could prevent the Roman Catholic Duke of York, brother of King Charles II and next in line to the throne, from ever succeeding to it. Clare Jackson’s absorbing new book demonstrates that, rather than simply being a local, historically specific phenomenon, the Exclusion Crisis was, along with other revolutionary moments and constitutional configurations, actually characteristic of an entire century in which Stuart England itself became a ‘synonym for instability’, especially when compared with Hanoverian Britain.

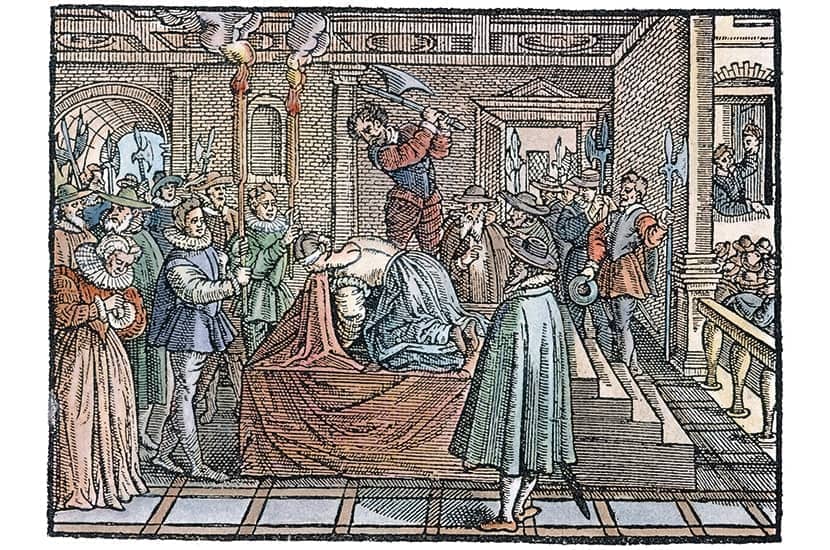

An effigy of the Pope ‘screamed’ as it burned – the sound of cats imprisoned inside being consumed by the flames

The ‘Devil-Land’ of her title is the name given to England during this tumultuous period by an anonymous Dutch pamphleteer who, writing in 1652, saw the nation as a land of fallen angels which had executed a Stuart monarch, Charles I, and replaced him with a republican government. Whereas the pamphleteer used the label to describe an anti-monarchical regime, Jackson uses it to track the turbulence and chaos long before (and long after) the English civil war and interregnum. She traces everything back to Elizabeth I’s execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, another Stuart put to death amid widespread fears of popery, which haunted successive administrations. Her study ends with an analysis of the Glorious Revolution and accession of William and Mary, whose Protestant credentials ultimately trumped James II’s hereditary rights.

One of the great strengths of the book lies in its compelling depiction of the centrality of foreign brokers to key events in early modern British history, whether that be the dynastic manoeuvrings of the Jacobean and Caroline courts, Charles II quietly taking bungs from Louis XIV in order to raise enough money not to have to bend to the will of parliament, or Dutch republican involvement in fomenting the unsuccessful Monmouth rebellion of 1685.

While such an account of events is familiar enough, Jackson’s great trick is to present the Stuarts themselves as aliens, invited south of the border to govern England amid fears of the expansionist designs of powerful Catholic neighbours. She gets past the xenophobic anti-Scottish sentiment in some English primary sources by focusing on ambassadorial reports to ascertain how foreign observers viewed this imported dynasty.

Even if envoys and ambassadors could occasionally provoke the ire of their hosts — ‘Good God! What damned lick-arses are here!’ opined one observer of countless sycophantic delegations to the Cromwellian protectorate — foreign correspondents allow us to view well-known figures and reputations from different, unexpected angles. For instance, such letters can show how Charles II and the Duke of York’s experience of European exile following the execution of their father expanded their horizons (as well as hardened their attitudes towards English parliaments). The Venetian resident in England, Francesco Giavarina, was shocked and impressed when they were able to conduct a meeting with him in Italian. Another dispatch from Aachen in August 1654, where Charles had gone with his sister Mary to view the relics of Charlemagne, depicted the future libertine king in a less sophisticated light; while Mary devoutly kissed Charlemagne’s skull, Charles grasped his sword and compared it with his own.

For all of the narrative drive and richness of this study, it is, however, compromised by one of its central contentions. Stuart England throughout this century, Jackson claims, was not just turbulent and revolutionary but actually ‘a failed state’, and was viewed as such ‘by contemporaries and foreigners alike’. However, what this book shows beyond question is that, for all of its profound regime changes — from monarchy to commonwealth to protectorate and back again — the quotidian business of government never stopped, economies continued to function and no foreign army was ever actually required to ensure the rule of law (even if foreign armies always lurked at the edges of fearful imaginations).

Momentous transformations such as the accession of James I, the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the arrival of William and Mary were all achieved without heavy losses of life. Even during those desperately bloody years of the English civil wars, there was a sitting parliament. And throughout the period of commonwealth and protectorate — while many might have railed against the different regimes’ legitimacy — the authorities were courted or feared by foreign powers as major players in European and global politics.

Comments