The new movie Nuremberg, starring Russell Crowe as Hermann Göring and Rami Malek as his US Army psychiatrist, has had mixed reviews. The Spectator’s Jonathan Maitland hated it, describing it as an ‘obscenely ill-judged two hours’ filled with ‘egregious errors of taste, decency and judgment’. Some critics have given it four stars, but Peter Bradshaw in the Guardian called Malek’s performance ‘an eye-rolling, enigmatic–smiling, scenery-nibbling hamfest which makes it look as if Malek is auditioning for the role of Hitler in The Producers’.

The key scene comes when the American chief counsel Robert H. Jackson (played by Michael Shannon) fails to break Göring in the witness box, and the British barrister Sir David Maxwell Fyfe (played by Richard E. Grant) steps in to destroy Göring with a single question. This is an American movie, so the moment when the Brits save the day is over in less than five minutes.

‘Göring’s lips were drawn into a thin line and his hands were gripping the witness box. He was rattled’

The truth, as is clear from the Kilmuir Papers at the Churchill Archives at Churchill College, Cambridge, is far more interesting. (Kilmuir was the name of the viscountcy Maxwell Fyfe took in 1954.) They show just how close Göring came to derailing the whole judicial process.

For far from being the fat, pompous, overbearing and heavily drugged Reichsmarschall of the closing days of the war, Göring had lost weight in prison since his capture, was separated from the barbiturates he had previously used and was utterly focused on attempting to outwit the Allied legal team. If he managed to construct a narrative that exonerated the Nazi leaders of waging aggressive and genocidal warfare, it was feared that the whole point of the trials would be undermined.

Each of the major Allied powers therefore sent a high-level judicial delegation to Nuremberg to ensure there were no errors. The Russians sent the terrifying Andrei Vyshinsky, Stalin’s chief prosecutor during the show trials purges of 1936-38 which had resulted in the execution of tens of thousands of Soviet officials. His view of the Nuremberg proceedings was well illustrated at the first dinner of the Allied prosecutors: ‘I propose a toast to the defendants,’ he said with typical black humour. ‘May their paths lead straight from the courthouse to the grave!’

The Americans fielded a judicial team led by Jackson, an associate justice of the Supreme Court. Jackson had had a successful legal career despite never having attended law school. He had been America’s solicitor general and attorney general but a secret British Foreign Office briefing on him stated: ‘Opinions differ as to the depth and breadth of his intelligence.’ The British team was headed by Labour’s attorney general Sir Hartley Shawcross, MP, and Maxwell Fyfe, who as well as a barrister was also an MP and a former Tory solicitor general. Both men were considered among the most brilliant legal minds of their generation, a judgment that was soon to be convincingly reinforced.

Some 205 letters from Maxwell Fyfe to his wife Sylvia written from Nuremberg between October 1945 and August 1946 allow us a unique insight into the British team’s thinking during the trials, specifically in the course of the vital cross-examination of Göring. They shed fascinating light on the nerve-wracking moment when it was feared that Göring might pull off a remarkable coup.

Unlike Jackson, Maxwell Fyfe knew that the Göring in the courtroom was far removed from the bombastic idiot who had led the Luftwaffe to so many defeats during the war. ‘Actually Göring was extremely clever,’ he wrote to his wife on 21 March 1946 when the Reichsmarschall took the stand. ‘Very calm, factual and a little dull. Jackson is going to start his cross-examination. The oddity about his attempts so far is that they have no form or follow-up, but a wealth of carefully proffered material. Curiously enough for the effete Old Country, I get the impression that I have been brought up in a much harder and tougher school.’

So it proved: Jackson asked Göring about Nazi philosophy and practice, allowing him the opportunity to put Nazism in the best possible light. When Jackson tried to interrupt Göring’s answers he was overruled by the judge, Sir Norman Birkett, and most spectators would have agreed with the British diplomat Patrick Dean, who reported on the first day’s proceedings: ‘It was very disappointing and unimpressive and has been severely criticised here. He never pressed Göring on any of the numerous matters on which the cross-examination touched even though Göring was frequently lying.’

Birkett was even more disappointed. ‘The cross-examination had not proceeded more than ten minutes before it was seen that Göring was the complete master of Mr Justice Jackson,’ he wrote, ‘who despite his great abilities and charm and his great powers of exposition had never learnt the very first elements of cross-examination as it is understood in the English courts. He was overwhelmed by his documents, and there was no chance of lightning questions following upon some careless or damaging answer, no quick parry and thrust, no leading the witness on to a prepared pitfall.’

The next day went even worse: when Jackson thought he had caught Göring out on one document from 1939, he mistook the River Rhine for the Rhineland and the word ‘liberation’ for the ‘clearing’ of civilian river traffic prior to German mobilisation. When a stammering Jackson tried to save himself by claiming that Germany had kept war preparations ‘entirely secret from foreign powers’, Göring sarcastically replied: ‘I do not think that I can recall reading beforehand the publication of the mobilisation plans of the United States.’ At that point Jackson lost his temper, and the tribunal had to be adjourned for the rest of the day.

By the end of his cross-examination on the third day, in which Jackson was reduced to describing the trial as a ‘bickering contest’, it was clear that the Allies’ case was not being made in the watertight way that was necessary for the death penalty to be imposed.

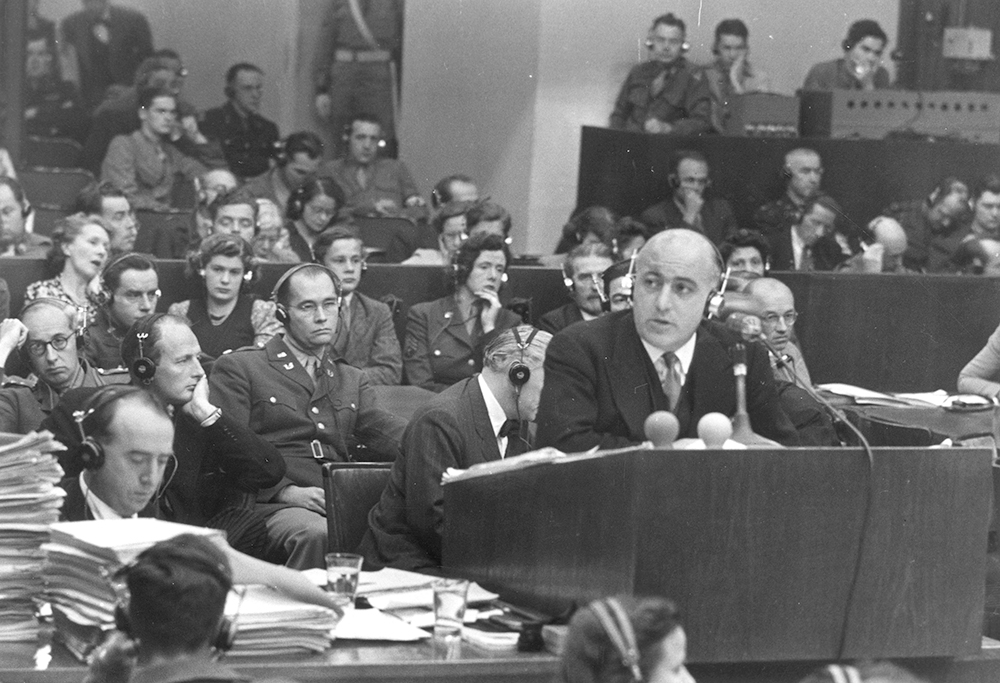

‘Then rose the British prosecutor, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe,’ reported Guy Ramsay of the Daily Mail, ‘his dark hair receding, his heavy face stern, his massive body impressive, his voice steady and controlled. Ruthless as an entomologist, he pinned the squirming, wriggling German decisively to every point he strove to evade, reducing his sudden spasms of legal quibbling, his spots of rhetoric to the hollow shams they were. Fyfe’s skills in cross-examination alone saved the reputation of the court.’

‘Ruthless as an entomologist, Fyfe pinned the squirming German to every point he tried to evade’

Those skills had been honed at the criminal bar in Liverpool, and in 1934 Maxwell Fyfe had become the youngest person to be appointed King’s Counsel for 250 years. He chose as his starting point the cold-blooded execution of 50 Allied airmen who had escaped from Stalag Luft III in Sagan, Poland, in what is known to history as ‘The Great Escape’. Quickly establishing his mastery of the documentation, dates and times, Maxwell Fyfe showed how Göring was lying and concealing the facts about his complicity in that war crime.

Asking short, precise questions about facts, which elicited brief affirmative or negative replies from Göring, Maxwell Fyfe set a series of traps that the over-confident Nazi – still preen-ing and smiling across to his fellow -defendants after his victory over Jackson – proceeded to fall into, one by one.

It became clear that Maxwell Fyfe understood the minutiae of Luftwaffe titles and procedure, enabling him to establish the level of Göring’s personal involvement in massacres. ‘By the end of the afternoon, journalists saw that Göring’s face had blanched,’ one history records. ‘His lips were drawn into a thin line and his hands were nervously gripping the sides of the witness box. He was rattled.’ He knew that he had met his match.

‘I think that my cross-examination of Göring went off all right,’ Maxwell Fyfe wrote to Sylvia on 21 March 1946. ‘Everyone here was very pleased. Jackson had not only made no impression but had built the fat boy up further. I think I knocked him reasonably off his perch.’ On the second day of the cross-examination, his suave, detached style caught Göring out in further lies. ‘Now, would you like to help me – you were most helpful last time – find the place?’ he said on several occasions, exploiting Göring’s earlier cooperativeness. This led to Göring himself finding extracts in documents that stated that ‘the Reichsmarschall was fully informed’ about various murders of other recaptured airmen.

Whenever Göring attempted to expound at length on a subject, hoping to recover his balance, Maxwell Fyfe merely interrupted, stating: ‘I have put my question: I pass on to another point.’ Göring, who earlier in the trial had been bullying, threatening and cajoling, ‘once challenged first resorted to bluster but rapidly became abject’. He had no answer about his responsibility for the invasion of Poland in 1939, and was led by Maxwell Fyfe to contradict himself on his alleged attempt to avert war with Britain that year.

Each time Göring made a statement about Holland, Belgium and Yugoslavia, Maxwell Fyfe was able to direct him to read out extracts from documents that disproved what he was alleging. When it came to the horrors of the Holocaust, and in particular Auschwitz, Maxwell Fyfe proved beyond reasonable doubt that Göring was lying when he said he had no knowledge of what was taking place there. None of this is in the movie.

Maxwell Fyfe’s thorough preparation, expertise, knowledge of all the tricks of the barrister’s trade and ability to keep the initiative against a clever and slippery antagonist led to him, in the words of one account, ‘scoring a success at a critical moment of the trial and in difficult circumstances’. On Saturday 23 March he wrote to Sylvia with evident relief to say: ‘We have at last finished with Göring and on Monday I hope to have a go at [Rudolf] Hess. Then about Wednesday or Thursday I hope to knock Hell out of Rib[bentropp] and if I could do the same for [Field Marshal Wilhelm] Keitel with reasonable speed we might get the trial within bounds. Jackson could do very little with slap-happy Hermann and I had to go in to prevent him being very firmly reseated on his pedestal.’

In the event, Göring escaped the noose by taking cyanide. To this day we do not know how it was smuggled into his cell, or whether it was in his pot of hair gel all along.

Although Jackson did not shine over Göring, he nonetheless produced the best summation of what the trials represented: ‘That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of law is one of the most significant tributes that power has ever paid to reason.’

Comments