‘Miss World 1970’ is the rather glorious title that Jennifer Hosten won. That was the year that the contest, then the greatest show on earth, was disrupted by feminist activists, who threw flour bombs at the host, Bob Hope. It is retrospectively called the foundation of the woman’s movement.The immediate trigger was Hope’s gag that he was happy to be in a ‘cattle market’, after which he mooed. The contest, and the protest, now dramatised in the film Misbehaviour, stars Keira Knightley — a world-class beauty — as Sally Alexander, the feminist leading the attack on the objectification of women that Miss World embodies. But cinema only slenderly knows feminism: the film Suffragette featured the equally beautiful Carey Mulligan as an oppressed laundress.

Hosten’s book is not good. It is written in the quasi-royal style of a press release put out by a semi-fictional great lady; but it is fascinating if you don’t know any successful beauty queens. I do — and the best ones I’ve met are like Hosten. Perhaps as a protective measure (you cannot be this lovely and still safe unless your words and behaviour summon an invisible burka around you), they are intensely poised: they exude sexlessness, and resemble tiny icons to be worshipped rather than women. They are very charming, but they are waxy and remote, engaged in a competitive purity contest that feels like a circus of denial. I long to watch them cut loose.

Miss Sweden sulked and said she felt like a puppet. Miss France thought the other contestants ‘lacked class’

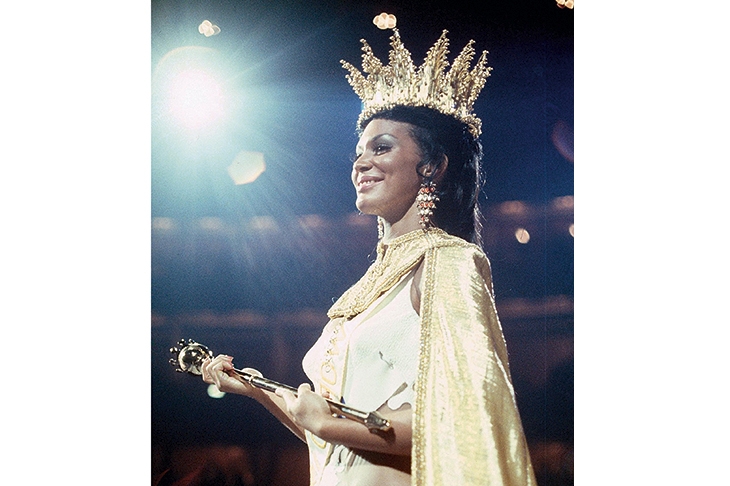

Hosten was Miss Grenada, the first black woman to win Miss World, and her book provides a handy how-to-do-it guide. Beauty is not enough: one must take princess lessons. She describes, in very literal prose, how she won, and it’s the same way as with any war: logistics. Rise early, be polite, find a personal hairdresser, don’t answer loaded questions about race, and drink two Heinekens on the night.

She has some semi-interesting backstage gossip. Miss Japan’s mother had a dream that a girl in a golden dress would be crowned, and it came true; the favourite, Miss Sweden, sulked throughout the contest and said she felt like a puppet; Miss France — ‘an outstanding girl’ — said that most of the contestants ‘lacked class’; at a party Miss Austria was sent to put on a bra.

Hosten comes close to anger only when she describes Eric Morley, the late founder of the contest; he was ‘bent on playing the role of lord and master’. She laments his ‘duck-like walk’, his ‘watery eyes and constant blinking’, his ‘abrasive manner’ and the way he referred to the women by their countries. Sometimes he strutted around the rehearsal stage with the crown on his head. She is pleased when he shouts so much that he loses his voice.

She has little to say about the protest, as she was backstage; but she describes Sally Alexander as ‘an intellectual’ — in a tone that sounds like whiplash. Her book touches on, but cannot resolve, the contradictions of feminism: is it a feminist act to allow yourself to be objectified if it benefits you? I don’t think so, and I suspect Hosten doesn’t either. At the end she writes: ‘As a result of its link to beauty contests, feminism, as a cause, has become better known.’ Well, yes, but that is a very partial truth.

Comments