Couldn’t we just skip to the end? I’m old enough to have seen this so often: must I sit through each dreary succeeding scene again?

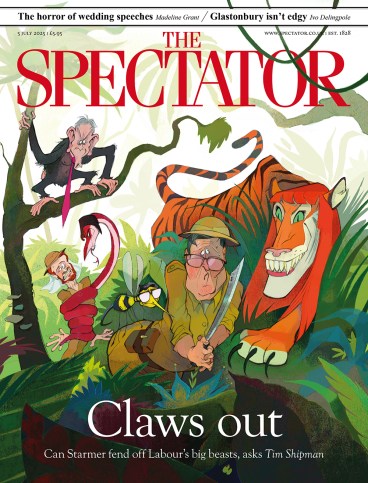

Parties in government are animals: they have natures; their natures do not change; they are incapable of being different animals; and what follows, follows. A Labour government finally runs out of money and enters a period of slow-motion disintegration, ending in a chaos of finger-pointing and blame-shifting, still whimpering about social justice as the bailiffs move in.

Already the suspense has gone. There will be many twists and turns, probably over years rather than months, before this government pulls apart at the seams; but, honestly, knowing where we’re going, I do ache to fast-forward. I’m 75. How many weekends do I have left to follow, with the breathless attention of my youth, each Commons Division result, each whips’ office crisis, each bend in a road whose destination is certain?

How many new names of the latest shadowy figures said to be influential in the Downing Street court do I need to commit to memory? How many on their way in and how many on their way out? How many jolly newspaper intros (‘The Prime Minister toyed with his scrambled egg, on the runny side as he always prefers, and pondered yet another bruising day ahead’), how many hints at inside information (‘There are murmurs, wistful rather than purposeful, about a change of leader’), how many scapegoats (‘Fingers are being pointed at Sue Gray/Matthew Doyle/Morgan McSweeney/Rachel Reeves’) before ‘It may not be long before…’ yields to ‘It was always inevitable that…’?

Permit me, then, to leapfrog straight to the inevitable. Parties have natures. Labour’s nature is colliding with the needs of the age. Coherent government will not survive the collision.

My civil partner – at heart a historian – believes in the Great Man in History theory: that extraordinary individuals can and must shape the destiny of nations. But I, like Marx, think the tide of history really is a tide: pulled by almost cosmic forces among which the clashes and convergences of economic interests, social change and sometimes pure chance exert more power than does the brief strut and fret of individual statesmen across history’s stage.

Parties have natures. Labour’s nature is colliding with the needs of the age

If anybody could have changed the Labour party’s nature it was Tony Blair – and he failed, even though everything was on his side: a plump economic legacy, the massive windfall that was North Sea gas, a driven but attractive personality, a vision of a new, cool Britannia for the 21st century, a strong and focused belief in a humane society fuelled by a vigorous capitalist economy, and a natural flair for political persuasion. Scarcely pausing for breath, he whipped onward those old nags, the national membership of the Labour party, the trade unions and the parliamentary party; and for ten years and three general election victories, with clever post-socialists like Alan Milburn, Peter Mandelson, Geoff Hoon, Patricia Hewitt and Tessa Jowell by his side, he built his vision of ‘New’ Labour. He even rewrote the socialist Clause IV of the party’s constitution. His ascendency ended the political careers of three Conservative leaders in succession. No Tory ever beat him in a general

election. So surely the party he led for 14 years and whipped behind his programme would have become a changed beast?

Not a bit of it. Under Gordon Brown, Labour lurched straight back into the collectivist, welfare-ist, market-sceptical ditch. After a briefish fling with a real Marxist, Jeremy Corbyn, it settled on a squishy, un-ideological lawyer inclined to take the line of least resistance. To say (after last week’s shenanigans over disability benefits reform) that ‘old’ Labour is back in the saddle would be too crisp. Rather, the parliamentary Labour party (PLP) remains a beast well capable of refusing a fence.

Why should we be surprised? What is the Labour party for, if not a welfare-ist vision of social justice? Come on! Imagine. You are a young adult keen to join a political movement, and choose Labour. Why? Is that likely to be because the party stands out as best equipped to make our free-market economy thrive? Is it likely to be because the party has a muscular attitude towards defence? Is it likely to be because you fear the public sector has become bloated by trying to do too much for too many people? Is it likely to be because you’re kept awake at night by worry about the nation’s fiscal health?

Of course not. Every party has its unique selling points. Labour’s are what it might call social and workplace justice. This is a mass-membership party allied to (and partly funded by) the trade unions, whose driving impulses will for more than a century have tended to filter out participation by those who do not share them. There’s nothing un-usual or improper about this – other parties too are shaped by the priorities and human types they attract – but it’s the reason why those of us in the media who bewail the PLP’s preference for caring over counting, for compassion over cost, are missing the point. Evolution has made the giraffe a beast with a long neck. Evolution has made Labour a beast with a tender social conscience. Don’t ask a giraffe to graze the lawn. Don’t ask the PLP to withdraw benefits from people with disabilities.

It is this creature’s misfortune to be put in charge at a point in history when the state is trying to do more than can be afforded, and the country needs a leader able to explain persuasively that expectation must be lowered and entitlement reduced. The Labour beast has not evolved and cannot be adapted for such a purpose. There are no villains here, and no heroes; but as necessity pulls one way and the nature of the beast pulls the other, a miserable four years lie ahead. But I know how it ends.

Next up: the two-child benefit cap. Ah well, here we go.

Comments