When Hatton Garden Heist ‘mastermind’ Brian Reader died aged 84 in 2023, it was estimated that he had made £200 million during his long criminal career. Reader shared his origins with other members of British criminal royalty, such as those behind the great train, Brink’s Mat, Security Express and Tonbridge cash depot heists – robbers who were all part of a long standing and highly resilient culture of skulduggery. For many of these men, a childhood in and around London’s pre-gentrified Docklands was like going to Eton.

The Docklands and its adjacent surroundings have long been centres of excellence for criminal practice. Self-employment and casual labour typified early industrial London and marked out its workforce as a breed apart, unfettered by the rigid, shift-based grind of heavy industry. When all else failed, casual labouring in the docks was the last resort; it was unreliable, poorly paid and dangerous. But the wharves and warehouses of London’s waterfront provided ample opportunities for thieving, dealing, ducking and diving.

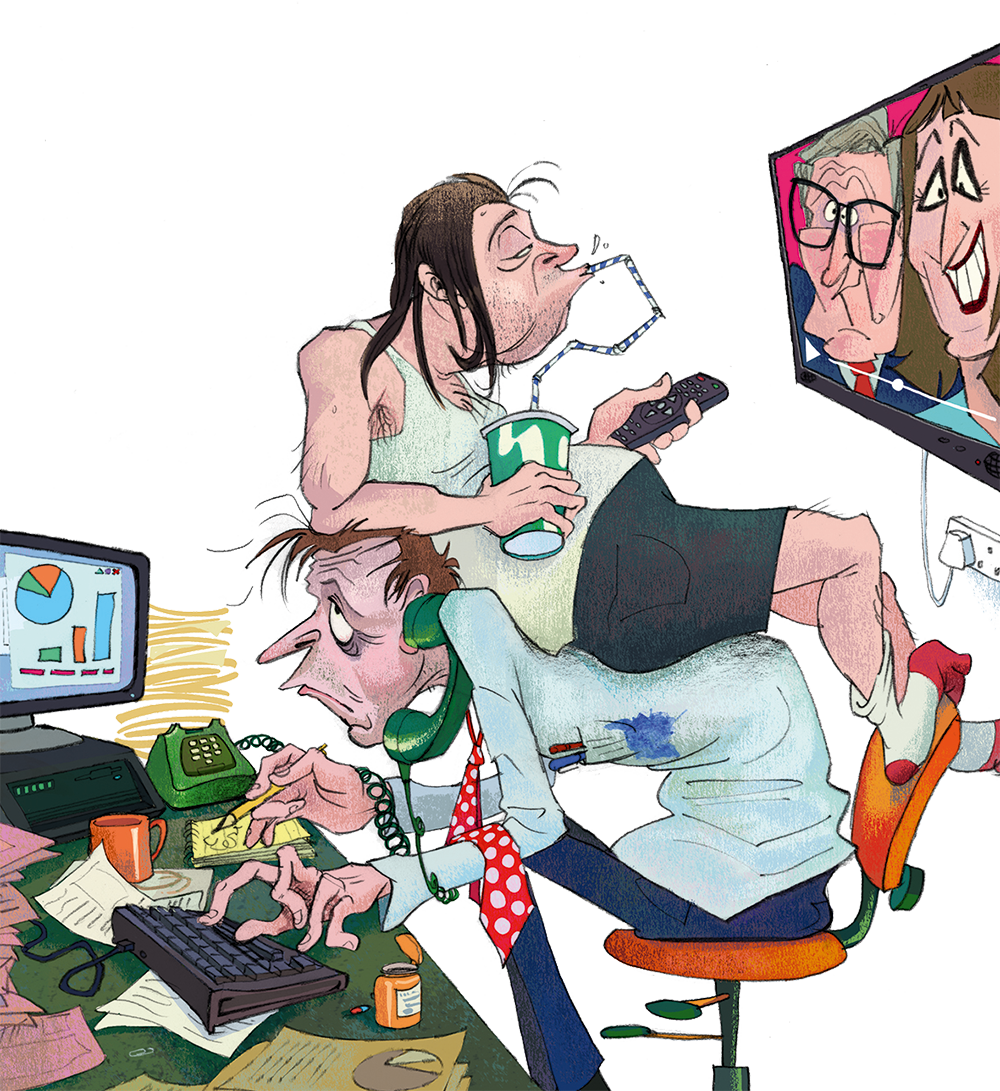

The wharves and warehouses of London’s waterfront provided ample opportunities for thieving, dealing, ducking and diving

It was quite normal to enliven an otherwise mundane existence with the odd roll of stolen cloth, a box of shirts or a prime piece of recently imported meat from Argentina or New Zealand. In the early 1960s, I was playing at the home of a schoolfriend when his docker father returned from work. He removed his work coat before taking off eight identical sweaters: the result of plundering a shipment from the Far East. When an apparently drunk man was rushed to hospital after collapsing on the pavement shivering and incoherent, the medical staff determined that the stricken man was probably suffering from hypothermia: the result of the frozen steaks, recently liberated from the nearby Royal Docks, that were secreted inside his trousers.

While theft and stolen goods networks became deeply embedded in this rugged culture, the practice of dealing in illicit goods spread to adjacent occupations. Even the most respectable were susceptible to a bargain, often after a brief reassuring pantomime to assuage any guilt:

Mickey: Hello Mary, I have got a lovely roll of material for you.

Mary: It’s not knocked off (stolen), is it?

Mickey: No, of course not, I got it from the auctions like the last lot.

Mary: All right, let’s have a look.

The pub was an ideal market place for ‘hooky gear’, often in close vicinity of the pub’s landlord and any visiting police officers. After all, everybody liked a bargain. Entrepreneurial women often played prominent roles in these stolen goods networks. Sally Shirt, or ‘Stratford’s Liz Taylor’, as she was known to City Arms regulars on account of her jet-black hair and extravagant jewellery, was one of the more high-profile such women; she was known for sitting in a haze of cigarette smoke taking orders for polyester shirts.

While many of London’s villains served their criminal apprenticeships in and around this environment, not all of the thieves and robbers were destined to be Marbella- or Morocco-bound. Terry – who I first met as a young man – would often accompany his much-adored lorry driving father on trips around London and the Home Counties. With a white mother and black father, he told me that ‘they took a lot of racist stick when they were out together in the street. He was a black man out with a white woman and it wasn’t the thing back then’.

Terry also found himself subjected to racism: ‘I had to look after myself,’ he says. Consequently he quickly gained a reputation for fighting as well as ducking and diving, and the death of his dad triggered a period of chaos, and an almost inevitable ten week spell in a detention centre for car theft. Terry started his working life as a van boy and delivery driver in and around the docks, before embarking on decades of roaming London in an old van equipped with a Guinness label in lieu of a tax disc and a pair of long-handled bolt cutters. When he was successful, his jewellery came out of the pawn shop, and it was pints all round as his fellow drinkers gorged themselves on stolen sweatshirts, jeans, razor blades or some other desirable contraband.

But after forty years of ducking and diving in the shallows of unlicensed capitalism, increasingly aware that time was running out, Terry took up a minor role in a huge counterfeit currency conspiracy, robotically pulling a lever on an adapted greetings card machine: a proletarian version of monetary easing. At the subsequent court hearing, he was described as a ‘threat to the fiscal wellbeing of the UK’, before, at the age of 58, being weighed off with a five-year sentence.

Containerisation was the beginning of the end for this working-class city within a city. By 1971, the Port of London’s workforce had shrunk to 6,000; and in the decade from 1966, the five Dockland boroughs lost 150,000 jobs, mainly in dock-related occupations. During the 1980s, the newly christened ‘Docklands’ morphed into prime development land, and these embedded tribes of working-class entrepreneurs began their long migration to London’s expanding periphery.

Everyone had to adapt. Targets became festooned with CCTV cameras, and lorries were fitted with trackers, while cheap legal imports undercut the ‘hooky gear’ knocked out by the likes of Sally Shirt. Ever resourceful professional thieves were used to being light on their feet, and segued into the drug trade that came to dominate both the economics and culture of crime.

One childhood acquaintance of mine, who proved equally adept at academic work and charming his teachers, ceased attending school at the age of 15. Instead, he opted for London’s early morning wholesale markets where he learnt the greengrocery trade from a close family member. It was only natural that he would eventually take over the driving seat of the family’s lorry. This afforded him the opportunity to be on the road during the hours of darkness. A natural networker, this friend was soon sought out by thieves who paid handsomely for their ill-gotten goods to be packed away with the potatoes and cabbages. He quickly became an expert in the illegal transport infrastructure which, when the crime market shifted, was to make him a key logistics specialist in the drugs market. He progressed from delivering loads or part-loads, to locating vehicles, drivers, buyers, sellers, safe houses and the dark corners of car parks where the CCTV cameras were permanently defunct. The last time I saw him he was standing proprietorially by a pallet of Polish lager waiting for an off-license to open.

Meanwhile those lurking at the edge of the stolen goods trade joined the serious criminal fraternity in a criminogenic free for all, as chaotic feral broods morphed into ‘crime families’ by merely picking up a parcel of contraband and selling at a profit. While a few remnants of dock-based crime firms continue to function on their ancestral territory, the more successful practitioners have retired to a substantial mock Tudor dwellings in the suburbs.

Despite being brought up by law-abiding parents, Jimmy always aspired to life as an outlaw. After a long career as a scaffolder, bouncer, robber, businessman and convict he neatly summed up this culture: ‘When I get the chance, I don’t go in the factory knocking my pipe out for a two bob job, I’m going ducking and diving with the people who know what the game is’.

Comments