Ministers may claim that ever-tightening Covid rules are proportionate and reasonable, but if enough members of the public disagree, then the government could have a real problem on its hands. Non-compliance to another lockdown wouldn’t need to be rampant: if even 10 per cent decide not to adhere it could blow a hole in lockdown’s effectiveness.

Last month, Professor Chris Whitty expressed concern over ‘behavioural fatigue’. At the weekend, senior behavioural experts questioned the government’s prospects of successfully imposing new measures after ‘party-gate’. One told The Observer that ‘trust has been eroded to a very significant level… If you don’t trust the government, why would you do what [it] asked you to do?’

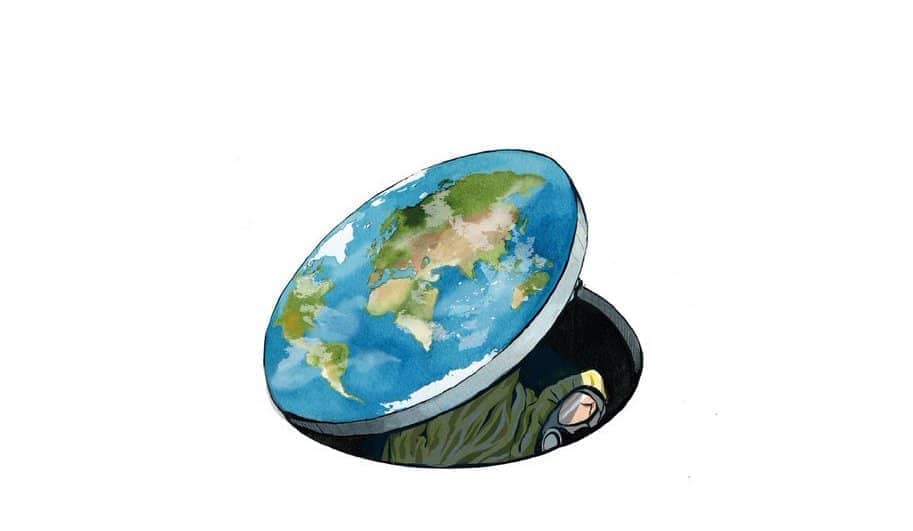

Millions of people obeyed the rules and received their jab believing this would make draconian restrictions unnecessary

Millions of people obeyed the rules and received their jab believing this would make draconian restrictions unnecessary. They may not mind masks, but they’ll be miffed if told this isn’t true.

Four in five over-12s in the UK have received both doses and 41 per cent have been given the booster. Last December, the government promised an end to lockdowns once we reached 15 million vaccinations. No wonder compliance is a concern. If tougher measures return, perhaps hidden fun will, too.

But some will disregard the rules out of economic necessity. Government erected scaffolding to support the economy at the start of the pandemic and managed to remove it in the autumn without the house collapsing. But what now? Plan B alone could easily knock 2 per cent off GDP — costing the UK economy a billion pounds a week — and force the taxpayer to stump up billions more to prevent a new wave of bankruptcies and job losses. Is the Treasury serious about reintroducing furlough or the self-eployment income support in the event of another lockdown? Can we afford it without huge cuts in other public expenditure? And when was the last time a minister uttered the terms ‘cost-benefit analysis,’ ‘impact assessment’ or ‘trade-off’? It’s thought that there was no economic impact analysis carried out to usher in Plan B.

Just yesterday, the New Economics Foundation suggested half of UK families have seen their disposable incomes ‘squeezed by an average of £110 in real terms a year’ since 2019. We’re in the foothills of a cost of living crisis, with inflation set to peak at close to 5 per cent according to the Bank of England. The most recent GDP figures showed anaemic 0.1 per cent growth for October. Business confidence is being shattered by the prolonged uncertainty. Today’s unemployment data may look upbeat — at just 4.2 per cent — but it’s measuring a pre-Omicron period.

Before Covid, there were around five million self-employed people in the UK, making up 15 per cent of all those in work. Today, 810,000 self-employed are in construction. 340,000 are in ‘wholesale, retail and repair of motor vehicles’. 165,000 work in manufacturing. These are not roles that can be carried out from the comfort of the home office.

In fact, very few can. At the start of this pandemic, one economist predicted just 15 per cent of the workforce would work from home productively. Technological innovation may have driven the figure up, but it’s entirely possible that some workers will take a more casual approach to pings or positive tests. Some won’t feel they have a choice. They may be few but, as the Prime Minister is so fond of saying, a small percentage of a large number is still a large number.

None of this is to mention the longer-term issue that choices today could permanently dampen confidence in both government and public health officials to deal with crises in the future. The data suggest Omicron is staggeringly infectious, meaning that even stringent controls may have little effect on the rate of spread. Yet officials are talking about bringing them back anyway. Perhaps the majority will comply this time. But it may be the last.

Comments