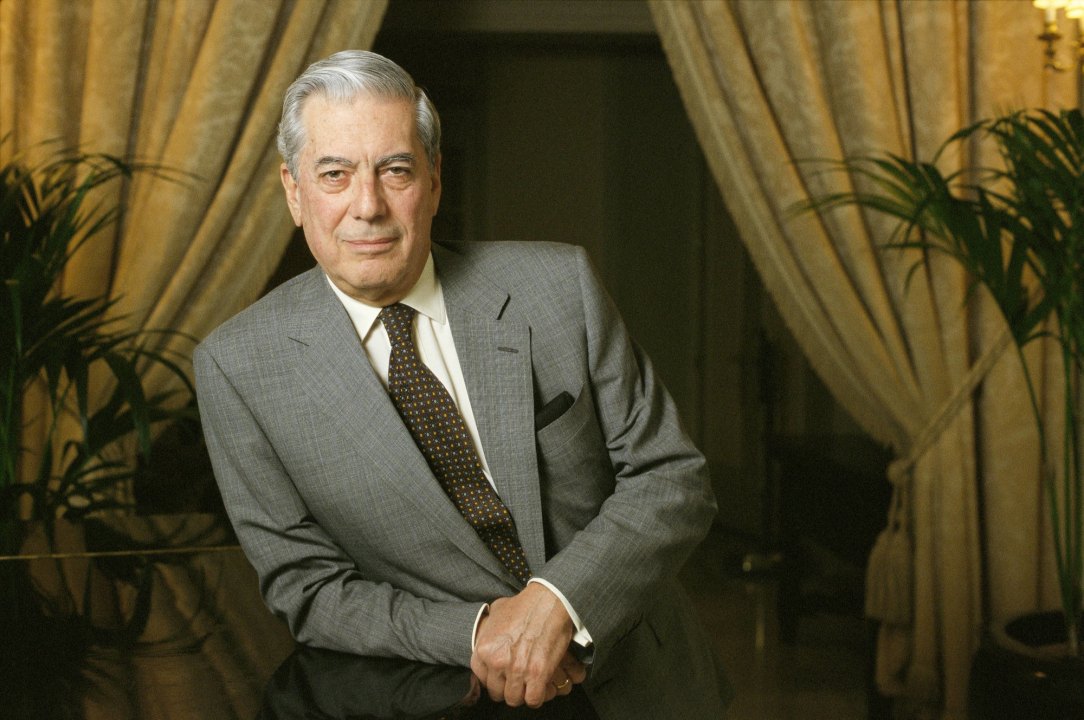

Most writers – like the vast majority of actors, artists and other luminaries of our culture – belong to the political left, but the death aged 89 of the great Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa reminds us that this is not always the case.

Most unusually for a Latin American author, Vargas Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010, was not only a proud Thatcherite conservative, but himself came within an ace of winning his troubled country’s presidency after temporarily laying down his pen and entering the political arena.

But like his great Colombian rival in literature, the Marxist novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez (who Vargas Llosa once decked with a right hook when the two writers had a violent altercation) the Peruvian author began his political life on the extreme left.

Like so many in a Latin America dominated by the USA, Vargas Llosa was inspired by Fidel Castro’s 1959 communist revolution in Cuba, and it was only after several visits to Castro’s socialist ‘paradise’ that the scales fell from his eyes and he realised that the island was one vast prison that persecuted and locked up free-spirited artists like himself.

Vargas Llosa went public with his conversion to conservatism after the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968 to crushed with tanks the ‘Prague Spring’. The novelist publicly denounced the Russian repression of the Czech experiment, and from then on he was a marked man in the eyes of Latin America’s powerful left.

The writer’s personal life was as colourful and controversial as his political stance. His best known book Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (filmed in 1990 with Keanu Reeves in the lead role) was a thinly disguised fictional version of Vargas Llosa’s own affair and marriage to his aunt Julia Urquidi.

Aged 19 in 1955, Vargas Llosa had fallen passionately in love with his 32-year-old aunt, and the couple had eloped and wed – defying Vargas Llosa’s father, who had threatened to put five bullets in his son as punishment for his impetuous action. The scandal was worsened eight years later when the writer fell for and married his 15-year-old first cousin Patricia Llosa who had come to stay with the exiled couple in Paris.

Once again defying convention, the writer left Julia and married Patricia, and they went on to have three children. In the 1980s Vargas Llosa fell in love once again – but this time the object of his affection was Margaret Thatcher and the political ‘revolution’ that she was leading in Britain.

The admiration was mutual – and Mrs T basked in the political love affair with the handsome author during the writer’s frequent visits to London. Meanwhile, his native Peru was falling into chaos, as it was wracked by a murderous Maoist guerilla movement known as the ‘Sendero Luminoso’ (Shining Path).

Vargas Llosa bravely spoke out against both the Maoist fanatics and Peru’s leftist dictator Alan Garcia, and put himself at the head of a right-wing citizens’ initiative calling for liberty, less taxation, and an end to both violence and state repression.

In 1990 Vargas ran for Peru’s presidency on an unashamed Thatcherite ticket. Victory seemed in his grasp, but in the run-off he was defeated by Alberto Fujimori, an ethnically Japanese candidate who had won the backing of Peru’s indigenous Indians. (Ironically, Fujimori proved as repressive as Garcia, but did succeed in stamping out the ‘Shining Path’ insurgency before being jailed himself for corruption).

Vargas Llosa returned to his writing desk. He continued to publish into his 80s. Books like

The Feast of the Goat an account of the assassination of Rafael Trujillo, the brutal dictator of the Dominican Republic, married Latin American Magic Realism with an epic narrative exposing political extremism.

The writer was not without his faults – he was personally vain and combative. But he was nonetheless a true friend of freedom in a violent continent where it is too often absent.

Comments