Poor John Dennis. In 1709, the playwright devised a novel technology to simulate thunder to accompany his drama Appius and Virginia. The play flopped and was promptly booted out of the theatre. To add salt to the wound, Dennis’s thunder-generating technique was stolen and inserted into a staging of Macbeth. He accused the producers of ‘stealing his thunder’, birthing the phrase that has long outlived his work.

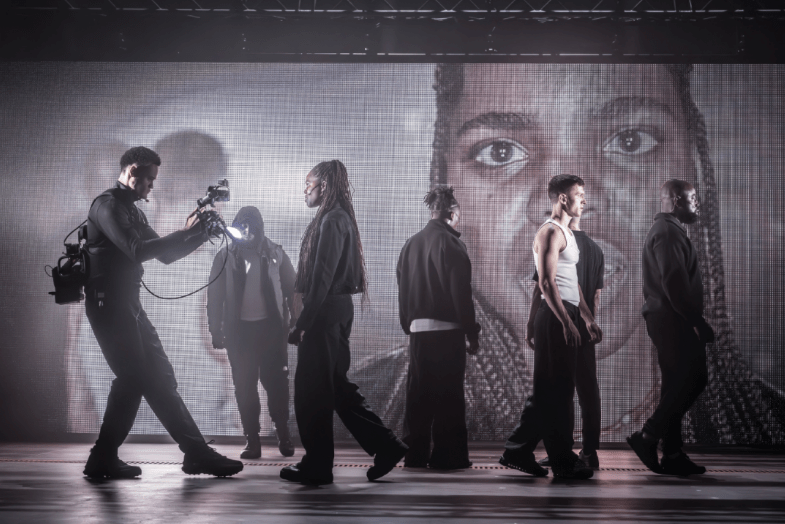

Stage technology has come a long way since. Directors have a toy box of high-tech smoke and mirrors at their disposal. Perhaps it’s more of a Pandora’s box. Live on-stage cameras are particularly in vogue. Watch them crawling all over Jamie Lloyd’s monotone Romeo and Juliet and Ivo van Hove’s ill-fated Opening Night. They’re even parodied in Inside No. 9 Stage/Fright. First for tragedy, then for farce: that’s how you know an artistic fad has overstayed its welcome.

Pioneered by director Katie Mitchell, real-time projections are not simply a directorial trick but have become a bona fide genre: ‘live cinema’. Her 2006 adaption of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, which won praise for its synchronisation of actors and technology, was perhaps its high-water mark. Her last London production, Bluets, at the Royal Court last year, was the kind of thing you might stumble upon in a dimly lit back-room of Tate Modern. It left me with a migraine, my eyes zigzagging between stage and screen.

Tech can of course work. But only when theatrical form follows function. The Seagull, a play about acting, art and artifice, is primed for disassembly. It has plenty to say about our terminally online age, something director Thomas Ostermeier recently played up in his anarchic production at the Barbican. Robert Icke’s 2017 modern dress Hamlet at the Almeida is another good example. In a play about deception, subterfuge and paranoia, the camera was the thing to ‘catch the conscience of the king’ in Act Two’s play within a play. A clever way to excavate the play’s roots for modern audiences. And on-stage technology could not have been more appropriate in Van Hove’s 2017 adaptation of Network at the National Theatre, a play about a newsreader’s very public breakdown.

But when technological spectacle takes centre stage, it often comes at the cost of the humanity that is the lifeblood of theatre. A classic recent example was Kip Williams’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which Sarah Snook was accompanied by a bank of cameras and monitors. Oscar Wilde’s genius was being squeezed within an inch of its life, cornered by lenses, wires and pixels.

‘Halfway through the performance a man came out to announce that the technology had broken down,’ remembers veteran actor Peter Eyre, former member of the RSC and the Old Vic Theatre Company. ‘Thank God,’ he thought, ‘I was eyeing up the exit.’ Compare the hyperactive Dorian Gray with Simon Stephens’s austere one-person take on Uncle Vanya. Both were commercially lucrative one-person shows festooned with awards and praise. The major difference was that Vanya was solely reliant on the actor’s craft to spark its audience’s imagination. Andrew Scott slipped into each character with seemingly trivial gestures. No tech required. Just an actor and the empty space, the imaginative heavy-lifting done by the audience. Technological maximalism just can’t compete with ascetic restraint.

‘I saw Peter Brook’s Tempest. They didn’t have microphones. They conjured a fantasy world just with their bodies. Jamie Lloyd’s production, hampered by terrible sound design, completely failed to do that,’ says Eyre.

We are lulled into a brainless daze; unprovoked, unchallenged, uninterested

Unsurprisingly, on-stage tech has changed the nuts and bolts of the actors’ craft. I felt slightly sorry for the actors in Bluets, one of whom was reading off a script, clearly overburdened with the prospect of simultaneously mumbling lines into a microphone and obeying the intricate demands of the technological choreography required to create this ‘live cinema’.

It’s not just the rhythm of the performances that is hampered by the tech intrusions, but the physicality of the performers too. ‘Actors no longer have to project their voices; they don’t have to fill the theatre with their bodies or performance,’ says Eyre, who cut his teeth touring regional theatres. ‘We developed muscularity in our voices. It was an unparalleled training.’

He is not the only member of the old guard who laments the loss of vocal connection with audiences. The Olivier award-winner Roger Allam has also expressed how much he longs for the acoustic warmth that radiates from an unmediated voice.

But many within theatre have no faith in audiences and their attention spans. Technological spectacle allows punters to shift their gaze from screen to stage with no effort. The result is the opposite of what you need for great art. Instead of Brecht’s alienation effect, distancing the audience from the play’s emotional gravity such that they might be able to pass intellectual judgment on what proceeds, we are instead lulled into a brainless daze; unprovoked, unchallenged, uninterested.

‘The worst thing is that it replaces the imagination. A play demands cognitive response. When you are confronted with all these screens you are too overwhelmed to imagine,’ says Eyre.

I worry that it goes deeper than unengaged audiences. Technological spectacles threaten to rip apart the fabric of Britain’s rich theatrical tradition, which has always prioritised writers. The task of the director should be to act as midwife: to interpret and deliver what the playwright has written, rather than rewrite the play.

Many of these tech-obsessed directors cut their teeth in continental Europe where Regietheater still reigns. One school of thought is that the origin of this director-centric theatre style lay in the scarcity of German playwrights after the war, which forced directors to absorb the writing responsibilities. Little surprise then that some writers go to extreme measures to cling on to artistic control. Harold Pinter went so far as to try and withdraw the performance rights of Luchino Visconti’s 1973 production of Old Times when the Italian director radically rewired Pinter’s play to include lesbian sex, full nudity, and singing. (Pinter flew out to Rome to see and jeer at it for himself.)

The UK’s exceptional ability to produce world-leading playwrights exists because of its artistic ecology, maintained by the bedrock of our collective reverence for the written text above all other aspects of a production.

The tech fanatics would do well to remember the words of Peter Brook in his manifesto The Empty Space: ‘A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all for an act of theatre to be engaged.’

Comments