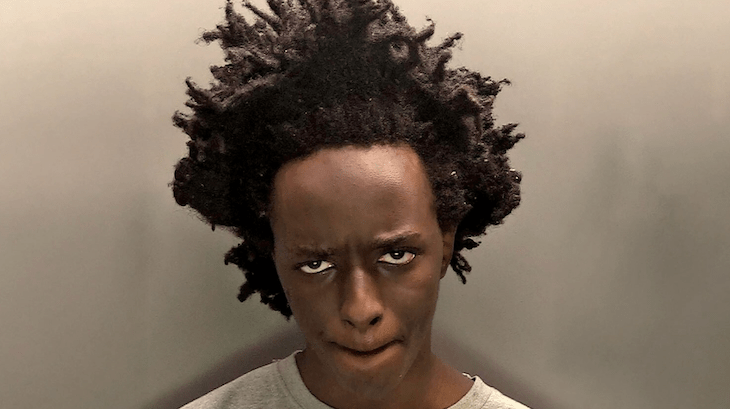

The Southport inquiry into the murderous frenzy of Axel Rudakubana has broken for half term. Officials who have been already damned by their own evidence of incompetence and disarray must be thanking their lucky stars that the accidental release of Hadush Kebatu from HMP Chelmsford has stolen the media’s attention. But this is a slow-motion disaster that has far to go.

It’s almost impossible to list the mountain of professional failures across our protective agencies that led to that fateful day in August 2023 and the national riots that followed. And we are only in the foothills of this investigation. The findings will be explosive and yet entirely predictable. The failures will likely illustrate a profound and systemic collapse in the UK’s safeguarding network. Isolated errors across different threadbare agencies compounded into foreseeable tragedy.

Before the attack, Rudakubana was referred three times to the Prevent counter-terrorism programme. Each referral was prematurely closed without proper escalation. This may have been due to inconsistent spellings of his name.

No case closure reviews took place as they should have. Mental health services at Alder Hey Children’s hospital failed to recognise his ‘toxic mix’ of behaviours at 13 – lack of empathy, fixation with extreme violence, and neurodiversity. Vital information was not shared between clinicians.

Rudakubana was discharged from Child Adolescent and Mental Health (CAMHS) services six days before he attacked children with a knife. He’d stopped coming to appointments and was refusing to take his medication, living as a recluse.

Rudakubana had been referred to a pupil referral unit after taking a knife to another school ‘to use it’. His teachers at the unit saw him as very high risk, but a mental health worker dismissed the worries of the head teacher there as racially motivated. Head teacher Joanne Hodson told the inquiry that she had a ‘visceral sense of dread’ that Rudakubana’s behaviour was building up to something. For that she was effectively called a racist.

Police were involved with Rudakubana and his family multiple times but failed to take proper action to minimise risks.

In March 2022 they found him in possession of a blade on a bus and he admitted he wanted to stab people. But they put his behaviour down to his autism. He was not arrested. His family seemed completely indifferent to these risks. A week before the Southport attack, Rudakubana’s father prevented him from travelling to his old school wearing the same black tracksuit and surgical mask he wore during the attack a week later.

At the heart of this infuriating tragedy is the persistent misreading of Rudakubana’s threats by multiple professionals who ought to have been focused on his risk to others. This was exacerbated by operational flaws meaning vital information wasn’t captured or stored or communicated. The lack of professional curiosity is extraordinary.

Denials by Rudakubana that he was a threat to others were taken at face value. I was reminded of this mentality when at a recent meeting of extremism professionals at the Home Office and other NGOs who deal in counter extremism. We were discussing Rudakubana and at the end of one struggle session I felt like the mad aunt in the attic. ‘Axel was a child with needs’ I heard, before interjecting that his victims were also children with needs, primarily the need not to be murdered by a young maniac who should have been treated as a threat not as a vulnerable child in need of ‘safeguarding’.

Risk management is a fraught business, particularly when it comes to damaged young people. But as this inquiry grinds on we are likely to hear more of the same. The public are entitled to ask: is this what an acceptable level of slaughter looks like? Are we not able to do any better? We are. But it will take a revolution to sort it out. We need a single national very high-risk management agency with the capability to track and control extremely dangerous people of any age both before and after they are in custody. What we have instead is a shameful mess.

Comments